29 April 2014 Edition

Imagining Ireland

Our literature and its depiction of rural life and the rustic image of the country

Modern Ireland’s image of itself is still defined by the work of Joyce, writing about Dublin, and Synge, writing about Aran, and their Irish worlds are long gone, but not forgotten, simply changed in a dramatically different way.

AN ENGLISH TRAVELLER, a sort of anthropologist, comes across a ‘curious scene’ in the midst of lonely mountains at the close of the day. He scratches his head, mystified.

“I could not help reflecting that these strong-bodied, though ill-clad, peasants might have found better employment on an evening admirably suited for ploughing.

“I noticed in a patch of bogland not far from the hut some ploughing gear lying haphazardly in a half-length of furrow, as if the peasant had flung it down on hearing a call to join the curious throng.

“Several peat-fires, which had been used apparently for the cooking of huge meals, had begun to die, but their relics still encircled the house and set it apart from the one or two others in the same district. The house itself, a miserable cabin, was crowded to the door with wild and picturesque figures.”

At the heart of this activity, the traveller is at pains to explain a “huge gaunt man was reciting what was apparently a very violent poem in Gaelic”.

Unable to understand what is being spoken, the traveller turns to his ‘Hibernian’ companion for solace.

The lines he needs to know are translated.

“Till through my coffin-wood white blossoms start to grow

“No grace I’ll beg from one of Cromwell’s crew.”

The poet is Eoghan Mor O’Donovan. He has heard that his family are to be evicted from their Gortinfliuch home but his wife Marie is pragmatic. “The poets will leave us in the end as desolate as we are now in this dawning.”

She asks her husband a question. “Have you thought of the days that will follow on the feasting?”

Eoghan Mor is ready with his answer. “Woman, the sorrow that has made us desolate has this night given birth to a song that will live forever; because of it my name and your name and our son’s name, which are woven into its amhrán metre, will not pass. Were I given my choice this moment to choose between Gortinfliuch and my song, to which would I reach my hand? This trouble that has come to our door is as nothing to the rapture in my song!”

William Butler Yeats

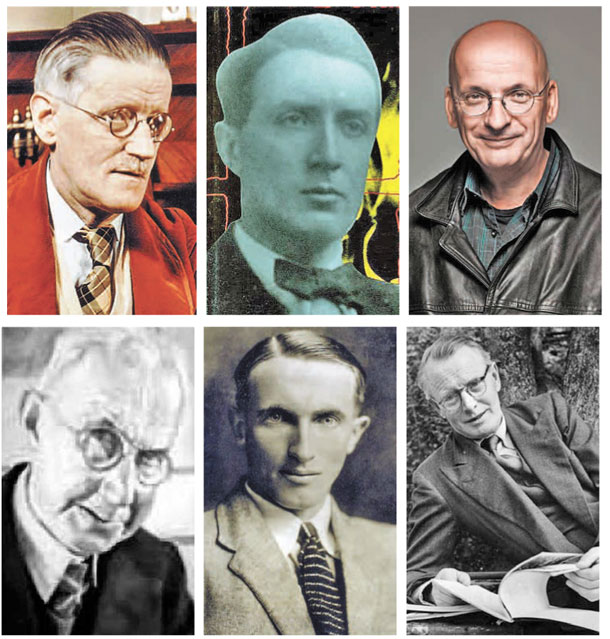

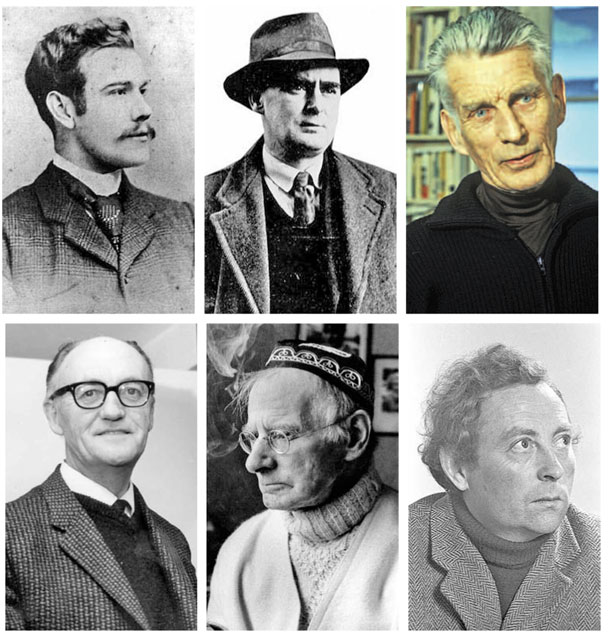

William Butler Yeats was apparently responsible for John Millington Synge’s presence on the Aran islands between 1898 and 1901. “Go to Aran Mór,” Yeats told him in a Paris hotel in 1896. “Live there as if you were one of the people themselves; express a life that has never found literary expression.” Synge, who was more of a cultural than a political nationalist, needed the people of Aran more than they needed him.

Yeats, the Sandymount-born idealist, desired a modern Ireland that was rustic to the core. He promoted a Celtic renaissance that would preserve identity and folklore. More crucially, it would give his own culture a crucial place in the new nationalist Ireland, which John McGahern acknowledged in 2001 when he put Yeats at the forefront of modern Irish literature.

“Yeats,’ said McGahern, “almost single handedly established a tradition that wasn’t there before. In fact, he paved the way for Joyce and Synge and you could say even [Samuel] Beckett.”

Synge, a pagan at heart, wanted the brutal truth, as much for himself as for any audience his writings might reach. His drama of the west, The Playboy of the Western World, upset a lot of people for its brutal realism.

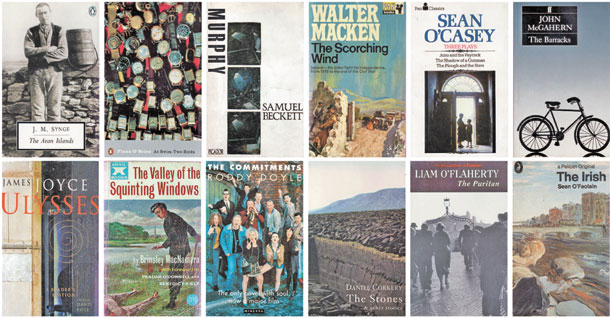

Charles Kickham’s 1879 novel Knocknagow or The Homes of Tipperary had heralded a literary culture that would continue with Brinsley MacNamara, Seán O’Casey, Liam O’Flaherty, Frank O’Connor and Seán Ó Faoláin.

They would shatter the rustic image, only to reveal a hidden mirror.

When Kate O’Brien, Walter Macken, Edna O’Brien and John McGahern attempted to look in the mirror they realised it was double-sided. Their early novels, which appeared to expose the reality of a distinctly colonial and disturbingly heirarchical paradigm, were banned.

No one was allowed to imagine what the mirror reflected, least it shatter into thousands of tiny shards that would reveal our true nature.

The Valley of the Squinting Windows

There is a sense of rural sameness about Brinsley MacNamara’s The Valley of the Squinting Windows, published in 1918, and John McGahern’s That They May Face the Sun, published in 2000. McGahern’s mirror was never going to be shattered. In contrast, MacNamara knew his mirror would cause trouble. “When a country has made a long fight for freedom there is a feeling, pardonable enough, that it is in a sense traitorous to delve too deeply into the frailties of one’s own people. If a writer . . . believes that the best service he can do his country is to raise its self-respect by attempting to lift it out of the dark realm of sham and cant and humbug by holding up the mirror truthfully, he is set upon from all sides as if he has committed a shocking crime.”

MacNamara did commit a crime. He took the romantic rustic imagery out of society. The Valley of the Squinting Windows instead depicted a fascistic regime fuelled by pernicious gossip, malicious envy, and religious hypocrisy.

MacNamara had touched a raw nerve. It was one thing to clash with the new bourgeoisie, which MacNamara as a director of the Abbey Theatre managed to avoid; it was an entirely different thing to clash with the religious extremists and the social purists, who more than anyone in the new nation were not going to stand back and allow artistic freedom of expression, especially if it revealed a social truth.

Aran Mór born O’Flaherty imagined in his novels the mood and the language of the urban poor, with the empathy of an informed and acutely sympathetic outsider.

Born into the tenement streets of Dublin that O’Flaherty so vividly described in The Informer, O’Casey developed a literary voice that could not have been more authentic.

His grand trilogy of plays, The Shadow of a Gunman, Juno and the Paycock and The Plough and the Stars, are now seen as an integral aspect of the emerging nation’s literary tradition, but his rugged imagery and political awareness made him an enemy of Yeats.

Some would say that, with O’Casey’s exile, the authentic voice, the revolutionary voice, the peasant voice and many other voices went with him. Only four years after partial independence, a new battle began – for the ownership of the emerging nationalist culture, and it continues today.

Joyce in his day deplored the romanticism attached to rural Ireland, to the west specifically, to Aran in particular and perhaps unfairly to Synge, whose playboy has become an alluding image.

Modern Ireland’s image of itself is still defined by the work of Joyce, writing about Dublin, and Synge, writing about Aran, and their Irish worlds are long gone, but not forgotten, simply changed in a dramatically different way.

Joyce, more than any other Irish writer (including those whose literary reputations have remained intact into the 21st century: Patrick Kavanagh, Samuel Beckett and Flann O’Brien in particular) has come to represent the elitist literary tradition of modern Ireland, which was never his own intention.

Kavanagh has a special place in the hearts of the traditionalists. Beckett is understood by few while his characters have informed the lives and loves of the new bourgeoisie. O’Brien is seen as the joker in the pack, but only by those who have attempted to understand him.

The Ireland of Joyce and Kavanagh and Beckett and O’Brien was once the place of all the people, with their cunning and guile, and wit and humour, and strategy and plan.

It was a complex place that, essentially, was about survival.

Jordan, Morrison, Doyle and McCourt

Neil Jordan, Danny Morrison, Roddy Doyle and Frank McCourt, with their brutally honest, Tarantino-like in-your-face snapshots of Irish society, shattered the stereotypical images of rural and urban Ireland.

Suddenly Ireland was a real place, no longer twisted and distorted into an arcadian place by adroit film-makers, revisionist scholars and prejudiced foreigners, it was the way it was, the way it looked in everyday life to everyday people.

Neil Jordan’s Ireland was a fairly ugly place. It was violent, selfish and very modern.

Angel, his film about a love-sick gunman, had an idealistic edge to it but its underlying current was not a river flowing free, it was damned, damned to hell and it looked very familiar.

We’d never been there, not in films and not in books.

There was more to come.

Danny Morrison’s West Belfast was a fiction with a twist, politics as art, and it was celebrated and criticised as such. West Belfast the novel was as authentic as West Belfast the place.

Its theme, the loss of innocence, was autobiographical, its subject matter highly political, which, Morrison later recognised, was “usually the death knell of art”.

Nevertheless, he had touched a nerve that needed to be exposed. “Art,” he said some years after its publication, “sublimates, illuminates, enriches and celebrates life, [and] also protests against the wickedness of humankind and injustice.”

Morrison would revisit his roots to produce The Wrong Man, a modern version of The Informer, with many of the same themes, expressing the reality of street violence, revealing an Ireland that was already very real to many of its inhabitants.

When Roddy Doyle wrote The Commitments and film-maker Alan Parker saw something that he could turn into an authentic modern musical in 1991, it was as if the old Ireland and the new Ireland had morphed into something that everyone recognised and wanted to celebrate.

This was an Ireland everyone could relate to, even if it seemed slightly unreal. By the time Parker put McCourt’s autobiographical sketch of 1940s Limerick lanes hardship on supersound widescreen just as the century was about to end, romantic Ireland disappeared up its own hole.

Rustic Ireland was revealed as a cruel hard place: repressed, lonely, sad, drunken, rainy, blustery and heartless.

But was it? Did Angela’s Ashes not represent an exile’s revisionist memory? Some people thought so. The radio phone-ins screamed with indignation when the people of Limerick realised what Frank McCourt had done to their city. It was as if they were saying, no we don’t want this reality, even if it is in the past, we want the romance we’re used to.

The image of the past

Now in the 21st century, with the hundredth anniversaries of 1916 and 1922 almost upon us, do we lament our past?

Of course we don’t.

Nothing has changed, just the props and the medium.

The image of the past is omnipresent in our future. What is more, we created this image ourselves and no amount of revisionism will change that.

“Must we Irish always be weaving fancy, living always in the fantastic world of a dream?” was the question Ó Faoláin asked in the closing sentences of his biography of Hugh O’Neill, whose imagined myth still mirrors the deep atavistic nature most of us carry in our breasts, leaving the foreign traveller to wonder why this windswept, rain-sodden island means so much to those who inhabit it.

But Seán Ó Faoláin was wrong. Eoghan Mor O’Donovan was right.

Nothing compares to the rapture of our visionary imaginations.