An Phoblacht follows in a long line of republican journals over the past 200 years since the first republican paper, the United Irishmen’s Northern Star, edited by Samuel Neilson in the 1790s; the Young Irelanders’ Nation of the 1840s, edited by Thomas Davis; the Fenian paper, The Irish People

1863-’65, edited by Thomas Clarke Luby, John O’Leary and Charles J

Kickham; and the numerous republican papers each decade of the present

century.

An Phoblacht follows in a long line of republican journals over the past 200 years since the first republican paper, the United Irishmen’s Northern Star, edited by Samuel Neilson in the 1790s; the Young Irelanders’ Nation of the 1840s, edited by Thomas Davis; the Fenian paper, The Irish People

1863-’65, edited by Thomas Clarke Luby, John O’Leary and Charles J

Kickham; and the numerous republican papers each decade of the present

century.

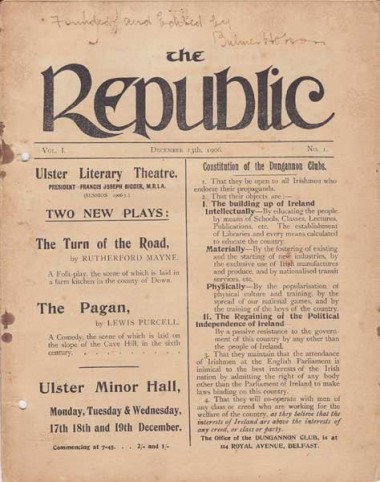

Although relaunched in 1970, the title An Phoblacht has a long and historic association with the Republican Movement and was used first used in its English form, The Republic, by the Dungannon Clubs in Belfast in 1906. The clubs were founded by Denis McCullough and Bulmer Hobson and their first task was to start a weekly paper. They managed to scrape together £60 and the first issue of The Republic appeared on December 13th, 1906.

Its aim, as set out in the first issue in a short article written by

Hobson, was the establishment of an independent Irish republic. In a

concise article he outlined the paper’s separatist policy. ‘‘Ireland

today claims her place among the free peoples of the earth. She has

never surrendered that claim, nor will ever surrender it, and today

forces are working in Ireland that will not be still until her claim is

acknowledged and her voice heard in the councils of the nations.’’

Its aim, as set out in the first issue in a short article written by

Hobson, was the establishment of an independent Irish republic. In a

concise article he outlined the paper’s separatist policy. ‘‘Ireland

today claims her place among the free peoples of the earth. She has

never surrendered that claim, nor will ever surrender it, and today

forces are working in Ireland that will not be still until her claim is

acknowledged and her voice heard in the councils of the nations.’’

Editor, manager and contributors were, of course, unpaid. The paper was mainly written by James J Good, Robert Lynd, PS O’Hegarty and Hobson. Lynd and O’Hegarty were based in London, where they carried out an active propaganda campaign through the Dungannon Club there.

Good acted as editor for about half of the brief life-span of the paper, as Hobson was in America to raise funds for The Republic. In the early issues PS O’Hegarty wrote a series of articles called ‘Fenianism in Practice’ which was a definite and important contribution to the philosophy of the Sinn Féin Movement.

After three months in America, Hobson was anxious to return to Ireland to prevent The Republic from collapsing. It was always in financial difficulty and was financed by the shillings and pence of members of the Dungannon Clubs, by a few pounds from Roger Casement and by several large sums which were presented to Hobson in various cities in America.

In June 1907 however, after only six months of publication, The Republic was overwhelmed by financial difficulties and was merged with The Peasant in Dublin.

Of the numerous papers produced by republican organisations during the years 1908 to 1921 when the establishment of a republic was an aspiration, not once was the title An Phoblacht used. Yet, during the years following the disestablishment of the Irish republic in 1922, on five different occasions papers with the title An Phoblacht appeared as the official organs of the Republican Movement.

During the decade prior to the Easter Rising in 1916, many militant papers appeared. These included Irish Freedom, (1910-1915), the paper of the IRB, edited by Patrick McCartan, and The Irish Volunteer, founded in December 1913 as the official newspaper of the newly-formed Irish Volunteers and edited by Eoin MacNeill until 1916.

During the decade prior to the Easter Rising in 1916, many militant papers appeared. These included Irish Freedom, (1910-1915), the paper of the IRB, edited by Patrick McCartan, and The Irish Volunteer, founded in December 1913 as the official newspaper of the newly-formed Irish Volunteers and edited by Eoin MacNeill until 1916.

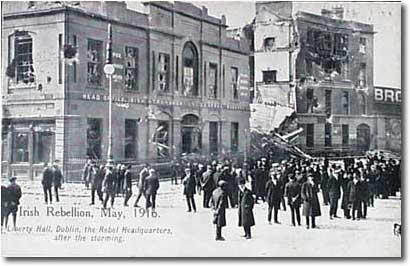

From 1916, when the Republic was proclaimed in arms to the end of the Tan War in 1921, during which the Republic was established, many underground newspapers appeared. Among these were: Nationality (1917-1919), edited by Arthur Griffith and Seamus O’Kelly; An tOglach (1918-1921), edited by Piaras Béaslaí; and the Irish Bulletin (1919-’21), the paper of the Dáil Publicity Department, edited by Erskine Childers and Frank Gallagher.

In January 1922, following the signing of the Treaty in December 1921 and the betrayal of the Republic, the title Poblacht was chosen as the title for a new republican newspaper.

On January 3rd, four days before the Dáil vote on the Treaty, anticipating what lay ahead, three republicans opposed to the Treaty, Liam Mellows, Frank Gallagher and Erskine Childers, founded a newspaper, Poblacht na hÉireann (Republic of Ireland). The editorial committee included such republicans as Cathal Brugha, killed later in the year following the beginning of the Civil War, and Máire Mac Swiney, sister of Terence Mac Swiney who died on hunger-strike in Brixton Prison in October 1920.

Poblacht na hÉireann, under the editorship of Gallagher, was issued at a time when all the national daily papers — except the Connaughtman

of Sligo — were in favour of the Treaty. It reflected the ideals of the

republican leadership which was soon to be in arms against the Free

State regime.

Poblacht na hÉireann, under the editorship of Gallagher, was issued at a time when all the national daily papers — except the Connaughtman

of Sligo — were in favour of the Treaty. It reflected the ideals of the

republican leadership which was soon to be in arms against the Free

State regime.

In the paper, Childers put a strong case for the republican side, including cold, analytical facts on dominion status in theory and the hard facts of the Treaty’s Defence Clauses in reality.

The issue of January 5th contained, side by side, the Treaty and Document Number Two, de Valera’s alternative to the Treaty, showing how important were the differences between them. The counter-proposal, Childers wrote, was ‘‘neither a dead negative to the English claims nor a humiliating sacrifice of Irish rights. It is an earnest effort to go to the utmost lengths possible in meeting England’s fears and prejudices without sacrificing any essential rights on the sovereign status of Ireland.’’

After February, and the acceptance of the Treaty by the Dáil by 64 votes to 57, the small journal, Poblacht na hÉireann, was edited by Childers. A fine propagandist with a natural flair for journalism, he had been Dáil Éireann’s Director of Publicity and one of the editors of the Irish Bulletin during the Tan War.

In the work of explaining the worst features of the Treaty and counteracting misrepresentations, Childers, through the columns of Poblacht na hÉireann, which he brought out once or twice a week, played a major part.

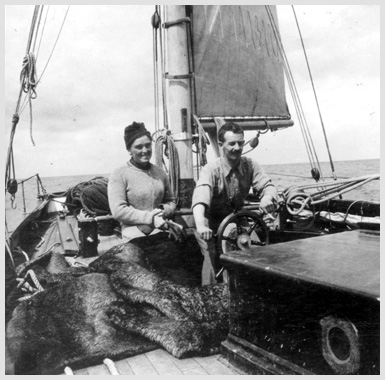

Following the failure of the Collins/de Valera Pact of June 1922, and the outbreak of the Civil War later in the month, Childers joined the IRA as a Staff-Captain but confined himself to the important work of propaganda.

Moving along with the brigade on the Cork-Kerry borders, he ran a mobile printing press with the assistance of Roibeard O Longphuirt of the Lee Press. He produced 20,000 copies weekly of Poblacht na hÉireann, sending it to embassies, newspapers, all organisations in Britain and also into jails and among the flying columns, lifting their hearts as he put their case so cogently.

In November 1922, while on his way to Dublin to meet senior IRA leaders, Childers was arrested and was executed by a Free State firing squad in Beggar’s Bush Barracks on November 24th.

With the death of Childers, the IRA lost one of its most effective propagandists and it meant the end of Poblacht na hÉireann.

During the following months, until the end of the Civil War in May 1923, a small paper, Eire, produced in Scotland, in order to avoid censorship, and edited by Countess Markievicz, published the republican position and in particular highlighted the appalling conditions being endured by over 11,000 political prisoners in jails and internment camps throughout Ireland.

In 1924, following the end of the Civil War and the release of the last political prisoners, the Republican Movement was at its lowest ebb for years. In that year two republican papers, Eire, and The Irish Nation, were in financial difficulty and finally merged, forming a new weekly, Sinn Féin. Soon afterwards it ceased publication and was subsequently replaced by An Phoblacht.

By the mid-1920s, the IRA had become suspicious of all political parties and began to distance itself from Sinn Féin.

An Phoblacht, as the official paper of the IRA, first

appeared on June 20th, 1925, under the editorship of Patrick Little.

Among the contributors were Peadar O’Donnell, Frank Gallagher, Frank

Ryan, Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington and Fr Michael O’Flanagan.

An Phoblacht, as the official paper of the IRA, first

appeared on June 20th, 1925, under the editorship of Patrick Little.

Among the contributors were Peadar O’Donnell, Frank Gallagher, Frank

Ryan, Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington and Fr Michael O’Flanagan.

Within a short time, the weekly An Phoblacht had an estimated circulation of 18,000 copies. It maintained a constant criticism of the Cosgrave administration in the Free State. In early 1926 Peadar O’Donnell, author, trade union organiser and socialist, succeeded Little as editor of An Phoblacht and was assisted by Frank Ryan and Diarmuid Mac Giolla Pádraig. The paper soon had about 30,000 to 40,000 subscribers and a readership of many times that number. It was the organiser, the educator and the policy-maker of the IRA and its supporters.

Under O’Donnell’s editorship an immediate change became apparent. While it still maintained a strident campaign against the appalling conditions in Free State jails, it began to emphasise social and economic issues which received extensive coverage, in particular the huge number of people emigrating from the 32 Counties.

Almost by chance, an issue presented itself which dramatically offered the possibility of linking political agitation for the betterment of the poor with the national struggle against British imperialism and which was to dominate the columns of An Phoblacht during 1928 and ‘29. This was the campaign for withholding payment of the land annuities in the 26 Counties.

The payment of land annuities was fiercely opposed by O’Donnell and by 1928 An Phoblacht was carrying almost weekly headlines stressing some aspect of the problem. Yet despite the oppostion of some IRA leaders to the paper being used by O’Donnell to spearhead the annuities campaign, clearly the agitation was too popular with rank-and-file IRA Volunteers to be cold-shouldered and the issue dominated the pages during the remainder of O’Donnell’s period as editor.

In 1930, O’Donnell was succeeded as editor by Frank Ryan who brought Terry Ward of Derry to assist him. O’Donnell, however, continued to contribute to the paper. Geoffrey Coulter, who had been assistant editor of An Phoblacht since 1929, felt aggrieved when Ryan took over as editor. Of Ryan he later wrote:

‘‘I had to admit he taught me a great deal, besides turning An Phoblacht from a quiet political weekly review with organisation notes into as lively a political newspaper as I’ve seen. Circulation grew from a few thousand a week to more than 40,000.’’

The circulation of An Phoblacht fluctuated dramatically

during these years, depending on the level of coercion. In 1930, when

Ryan took over as editor, it was down to 8,000 copies a week. Ryan

utilised his considerable knowledge of printing to revolutionise An Phoblacht.

‘‘He used pictures, cartoons and make-up as they had never been used

before in Ireland,’’ recalled Coulter, ‘‘with witty cartoons in Irish,

French and German as well as English on special occasions such as

Bodenstown.’’

The circulation of An Phoblacht fluctuated dramatically

during these years, depending on the level of coercion. In 1930, when

Ryan took over as editor, it was down to 8,000 copies a week. Ryan

utilised his considerable knowledge of printing to revolutionise An Phoblacht.

‘‘He used pictures, cartoons and make-up as they had never been used

before in Ireland,’’ recalled Coulter, ‘‘with witty cartoons in Irish,

French and German as well as English on special occasions such as

Bodenstown.’’

During the years 1929-’31, when coercion by the Cumann na nGaedheal government against republicans was at its height, An Phoblacht and its staff came in for particular attention from the ‘‘Broy Harriers’’, Garda detectives, many of them ex-IRA men, who specialised in harassing republicans. The new coercion legislation introduced in October 1931, which proscribed 12 organisations including the IRA and Saor Eire, forced many IRA Volunteers to go on the run. The military tribunal suppressed four issues of An Phoblacht in a row and the paper was forced to cease publication. It had ceased publication from March to April 1929, when O’Donnell was editor, for the same reason.

Ryan brought out a new publication, Republican File, the first issue of which appeared on November 28th. It expressed no opinions, taking its news from other publications, but despite this precaution, Ryan was arrested after two issues and lodged in Arbour Hill military prison and was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment in January 1932. Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington took over as editor.

During the general election campaign of February 1932 An Phoblacht resumed publication with O’Donnell as editor. The paper, with the approval of the IRA leadership, played a major part in the defeat of the Cosgrave regime and the election of a Fianna Fáil government led by de Valera.

One of the first acts of the new government, two days after it came into power on March 9th, was to release all political prisoners, including Ryan. He resumed his position as editor of An Phoblacht while Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington became assistant editor, following the lifting of the ban on the paper. after Fianna Fáil’s second electoral victory in 1933, relations between them and the IRA worsened.

There were also difficulties within the IRA over campaigning on social issues. Ryan and O’Donnell were the main supporters of the policy. An Phoblacht began advocating the division of large ranches, nationalisation of the banks and a conference (or congress) of all anti-imperialist forces. This sounded a great deal like Saor Eire, which had been engulfed and suppressed in a ‘red scare’ orchestrated by church and state.

As editor of An Phoblacht, Ryan publicised these policies enthusiastically. The IRA Convention of 1933, while itself formulating a programme of ‘‘national reconstruction and establishment of social justice’’, passed a resolution forbidding Volunteers from writing or speaking on social, political and economic issues. Following the convention, a split was developing between right and left in the IRA and Ryan was prohibited from writing anything for An Phoblacht without submitting a draft to the IRA leadership for vetting.

This went on until the spring of 1933 when, in protest at the censorship imposed on him by the Army Executive, Ryan resigned as editor of An Phoblacht. Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington, assistant editor, also left. Terry Ward of Derry and Liam Mac Gabhann of Kerry were appointed joint-editors and worked under the close supervision of Moss Twomey, the IRA Chief-of-Staff. Both were replaced in 1934 and Donal O’Donoghue, a member of the Army Executive, became editor.

The Army Convention of March 17th, 1934, split down the middle over the question of developing a new social policy. O’Donnell, Ryan and George Gilmore proposed the calling of a Republican Congress, which was defeated by a majority of one vote. All three resigned from the IRA and, on April 8th, 200 men and women met in Athlone and founded Republican Congress. O’Donnell also resigned from An Phoblacht.

Following the split, An Phoblacht, under the editorship of O’Donoghue, became less radical and throughout 1934 and early 1935 its articles and editorials carried out a vigorous campaign against the Blueshirts, a fascist organisation founded by Eoin O’Duffy in 1933, urging republicans to mobilise against the Blueshirts and defeat fascism. By 1935 the IRA was calling off its forces from the anti-Blueshirt campaign. An Phoblacht, while denouncing the Blueshirts, at the same time discouraged IRA Volunteers from being actively involved in the campaign against them.

In 1935, the Fianna Fáil government, having come to power three years earlier in the 26 Counties with the help of the IRA, now sought to crush the Republican Movement. The Military Tribunals, originally reactivated to deal with the Blueshirts, now began to imprison IRA members.

O’Donoghue, editor of An Phoblacht, was arrested and imprisoned. (By April 1936 there were 104 republican prisoners in Arbour Hill.) An Phoblacht faced a crisis every week. Its printing plant at the premises of the Longford Leader was usually surrounded by armed Free State troops. Sometimes they smashed the type, and other times they seized the entire issue of the paper. No paper could publish under such conditions and after weeks of being censored, the paper was finally suppressed at the end of June 1935. The last typed issue entitled The Republic came out on July 6th. By June of the following year the IRA was proscribed and hundreds of republicans, including Moss Twomey, the IRA Chief-of-Staff, were imprisoned on both sides of the border.

While the new Free State constitution was being debated during the summer of 1937, de Valera’s Fianna Fáil government lifted the ban on An Phoblacht. Tadhg Lynch, a close associate of Seán MacBride, who had replaced Tom Barry as IRA Chief-of-Staff, became editor of the new series of An Phoblacht.

Ryan, who had returned to Dublin to convalesce, having been wounded at the Battle of Jarama the previous February while fighting with the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War, moved close to the IRA again. Ryan and Lynch worked together in editing An Phoblacht, which was printed by Ralahine Press. It was to run for six months only, until July 1st, 1937, 26-County election-cum-referendum on the new constitution, after which it was immediately suppressed.

Within months of the final suppression of An Phoblacht in July 1937, another republican paper, The Wolfe Tone Weekly, appeared in September, edited and largely written by Brian O’Higgins, assisted by Joe Clarke, the veteran of the Battle of Mount Street Bridge in 1916.

Between 1937 and 1939, when Fianna Fáil coercion against the Republican Movement was increasing, The Wolfe Tone Weekly appeared every week. O’Higgins’ paper, though not as popular or as controversial as An Phoblacht, was a journal of some influence until its suppression in September 1939. His writing lacked the social content of Peadar O’Donnell’s, tending more towards Gaelic revivalism than socialism. The Wolfe Tone Weekly was, however, well edited and laid out.

During the two years of its existence and faced with suppression at any time, The Wolfe Tone Weekly endeavoured to promote the policies of the Republican Movement and, through contributors such as Jimmy Steele, at the time serving seven years in Crumlin Road Prison, Belfast, and Brendan Behan, it did much to educate republicans in the history of Irish republicanism. After the beginning of the IRA bombing campaign in English cities in January 1939, The Wolfe Tone Weekly continued to appear, but was finally suppressed in September, following the introduction of internment without trial in the 26 Counties. (Internment had been in operation in the North since December 1938.)

During the years of internment (1939 to 1945) when hundreds of republicans were detained in both the North and the South, no republican paper appeared. Two underground news-sheets — the weekly War News, produced by Charlie McGlade, Seán MacNeela and Seán MacCaughey from 1939 to 1943 and the monthly Republican News, edited by John Graham and later Tarlach O hUid, from 1942 to 1943 — appeared sporadically during these years. Of necessity their circulation was limited.

By the summer of 1943, with the IRA North and South virtually decimated by arrests, with most republicans either interned or imprisoned, both War News and Republican News had ceased publication.

With the ending of internment in 1945 and the release of the last political prisoners in December 1946, republicans set about rebuilding the Republican Movement and reorganising the IRA.

One of the more important developments for republicans came in May 1948 with the appearance of a small monthly paper, the United Irishman, edited by Seamus G O’Kelly.

The small, blurred United Irishman was a long way from the militant An Phoblacht edited by O’Donnell and Ryan in the ‘20s and ‘30s, but it was a beginning and a sign that Sinn Féin was not dead. It carried accounts of commemorations and through its many historical articles it told a new generation about the indignities suffered by Irish patriots at the hands of the British and Irish authorities in the past and blended Fenianism and commentary on the political situation in the North with attacks on the Fianna Fáil and Coalition regimes in the South.

The United Irishman played an important part in developing sympathies with and support for the Republican Movement during the early ‘50s and eventually from the 1956 to 1962 IRA border campaign.

Shortly after the official ending of the campaign in February 1962, Denis Foley took over as editor of a United Irishman increasingly concerned with economic and social issues in Ireland. The space given to historical articles declined and the analytical articles became more contemporary.

Throughout the early ‘60s the columns of the United Irishman reflected the policies of the leadership of the Republican Movement, placed less emphasis on the armed struggle and directed the Movement towards social agitation. In 1965 Foley resigned as editor of the paper and was replaced by Tony Meade. Under Meade’s, and after 1967 Seamus O Tuathail’s editorship, the United Irishman increasingly agitated against the appalling housing situation, ground rents, fishing rights and other social issues. Many republicans were gravely disturbed by the running down of the IRA. While many republicans were expelled or ousted during this period and many more drifted away, some stood their ground and were determined to do something to stop this betrayal of the republican cause.

In early 1966 a small group of Cork republicans, who fiercely disagreed with the trend of the Movement, secretly published a paper, An Phoblacht, which was extremely critical of the IRA for refusing to take action in the North and scathing in its attacks on the leadership of the Republican Movement for concentrating solely on social issues and ignoring the question of British occupation in the Six Counties.

An Phoblacht, published and widely distributed in Cork, continued for about two years, but ceased publication long before the campaign for civil rights gained momentum in the North in August 1968.

It was not until July 1969, on the occasion of the repatriation of the bodies of Barnes and McCormack at Mullingar, County Westmeath, that the republican leadership was publicly denounced. Jimmy Steele, the veteran Belfast republican, in a fiery oration, severely criticised the policies being pursued by the leadership of the Movement, the attitude of the leadership that the struggle for civil rights was a process by which the Six-County state could be reformed and finally, the running down of the IRA.

Steele received tremendous support for his stand, especially from veterans of the 1939 campaign. His speech and, more urgently, the pogroms in Belfast, the arrival of British troops in the North in August and the need to reorganise the IRA to defend the nationalist population, was a turning point for the Republican Movement. Within six months the inevitable split in the Movement had occurred and the elements so severely criticised by Steele became known as Official Sinn Féin — now the Workers’ Party and the Democratic Left following a further split.

Following the split in the Republican Movement in January 1970, one of the tasks of the leadership was the publication of a new republican paper as soon as possible. The first issue of the new monthly paper, An Phoblacht , under the editorship of Seán O Brádaigh, appeared on January 31st.

An Phoblacht, with a circulation of 20,000 copies per month (which was to rise steadily over the next two years) carried in-depth analysis of the new policies being formulated by the reorganised Movement, articles on various historical topics, organisation notes and reports of events in the North.

In the summer of 1972, Coleman Moynihan succeeded O Brádaigh as editor and in August An Phoblacht moved from its offices at 2A Lower Kevin Street, Dublin, to Kevin Barry House, 44 Parnell Square. On October 1st, An Phoblacht became a fortnightly paper. Eamonn Mac Thomais, the Dublin historian and author, took over as editor from Moynihan, following the latter’s arrest in November and within a few months, made major changes to the paper, with improved lay-out and more news reports. It eventually became a weekly paper on March 4th, 1973, with a circulation of 40,000 copies per issue.

By this time An Phoblacht had become a target for increased harassment from the Garda Special Branch. In July 1973, Mac Thomais was arrested and charged with IRA membership at the Special Court in Dublin and the following month was sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment. He was succeeded as editor by the Dublin journalist Deasún Breatnach.

Having completed his sentence in July 1974, Mac Thomais once more became editor of An Phoblacht, but within two months he was arrested during a raid on the paper’s offices and again sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment. During the following years, when the establishment, through Section 31, attempted to stifle news from the republican viewpoint, An Phoblacht, edited at different times by a number of people including Gerry Danaher (1974-’75), Gerry O’Hare (1975-’77) and Deasún Breatnach (1977-’79), performed a vital role in publicising the republican position in the 26 Counties.

While An Phoblacht was mainly distributed in the 26 Counties during the 1970s, the republican paper most widely read in the North was Republican News, which was founded in Belfast in July 1970 by the veteran republican, Jimmy Steele.

The four-page monthly, Republican News, edited and almost exclusively written by Steele, soon had a circulation of 15,000 copies a month. Steele died in August, and was succeeded by Proinsias Mac Airt.

Production and distribution of Republican News increased after the introduction of internment in the North in August 1971, even though some members of the paper’s editorial board were arrested. The two remaining board members started printing the paper weekly from the end of September.

Between 1971 and 1975, a number of Belfast republicans edited Republican News, including Proinsias Mac Airt (1970-’72), Leo Martin assisted by Henry Kane, (1973-’74) and Seán McCaughey (1974-’75).

The mid-1970s saw significant developments for Republican News. In 1974 it changed to newspaper format, with eight large pages and at the end of the summer the paper moved to its first permanent offices at 170 Falls Road. In mid-1975 McCaughey was replaced as editor by Danny Morrison, one of the recently-released internees, who had a natural flair for publicity. Under the editorship of Morrison the paper was reorganised. Layout was made more attractive, the content was vastly improved and the paper became more professional and more relevant to the huge readership.

In 1978, following his imprisonment in the H-Blocks at Long Kesh, the late Bobby Sands, using the pen-name ‘Marcella’, became a contributor to the paper, describing in detail the appalling conditions in the H-Blocks.

Throughout 1978, the staff of Republican News came in for increased harassment by the RUC and British Army and the offices on the Falls Road were regularly raided and issues of the paper seized. The paper, which by then had a circulation of 30,000 copies weekly, managed to overcome these raids, and had emergency editions on the streets within days.

In the autumn of 1978, following years of debate, it was announced that both republican papers, An Phoblacht and Republican News, would amalgamate under the title of An Phoblacht/Republican News. The essential thinking behind the merger, according to an editorial in Republican News of January 20th, 1979, was:

‘‘To improve on both our reporting and analysis of the war in the North and of popular economic and social struggles in the South… the absolute necessity of one single united paper providing a clear line of republican leadership… [and] the need to overcome any partitionist thinking which results from the British-enforced division of this country and of the Irish people.’’

The first issue of the new paper, An Phoblacht/Republican News (AP/RN), edited by Danny Morrison, appeared on January 27th, 1979.

During the early ‘80s, AP/RN was to the fore in reporting many issues, including the appalling conditions in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh, the torture of prisoners in the interrogation centres of Castlereagh and Gough Barracks, the H-Block/Armagh Prison hunger strike of 1980, the seven-month hunger-strike in Long Kesh from March to October 1981, during which ten republican prisoners died, and numerous other political, social and economic issues throughout the 32 Counties.

In October 1982, Mick Timothy, who had been Southern political correspondent of the paper since 1980 and author of AP/RN’s most popular column, ‘Burke at the Back’, succeeded Morrison as editor.

The improvements in the style, lay-out and journalistic content of the paper which had continued steadily since the amalgamation were even more marked under Timothy’s editorship. One of the most significant changes was the expansion of the paper from 12 to 16 pages, which allowed for greater coverage of social, economic and political issues throughout the 32 Counties.

Following Mick Timothy’s sudden death on January 26th, 1985, he was succeeded by Rita O’Hare, who had worked as a journalist on the paper since her release from Limerick Prison in 1979, having completed a three-year sentence.

In January 1990 Rita O’Hare left AP/RN, having been one of the longest-serving editors ever, to work full-time as Sinn Féin Director of Publicity. She was replaced by Mícheál MacDonncha from Dublin and then by Brian Campbell.

Mícheál was succeeded by Armagh man Brian Campbell in 1996. He went on to work in Leinster House with Sinn Féin TD Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin. Brian Campbell left the paper in 1999 to concentrate on his writing and to work with Newry Armagh Assembly member Conor Murphy.

In 1999, Martin Spain, a Dubliner, stepped into the breach. Martin began work for the paper in 1989 as a staff reporter, just weeks before the first computers arrived in the Parnell Square headquarters. Martin stepped down in July 2005. He was succeeded by Seán Mac Brádaigh.

Seán Mac Brádaigh had previously worked as a journalist with An Phoblacht for ten years in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s. A leading Sinn Féin activist in Dublin, Seán assumed the editorship in the centenary year of Sinn Féin, overseeing the latest relaunch of the republican paper in September 2005.

An Phoblacht was the first paper in Ireland to go online and in August 2003 launched a revamped new website, at www.anphoblacht.com.

In 2010, faced with a fast-changing media world, An Phoblacht also changed and moved to a monthly publication schedule with a new look, more pages and a more modern website under new editor John Hedges, who has been associated with the paper since 1981.

An Phoblacht is now a high-quality glossy magazine, published quarterly, under new editor, Robbie Smyth.