7 April 2022 Edition

Remembering the forgotten Denis Holland

• Denis Holland's 'Ulsterman' journalism proved to be a potent mixture of satire, scorn, and sarcasm

One of the joys of historical research, arguably the greatest joy, is the discovery of people buried in the thicket of the past who have not been given their due. So, I am delighted to exhume Denis Holland, who surely merits a prominent place in the republican pantheon.

It would be an exaggeration to claim that Holland, editor, publisher, pamphleteer, novelist, poet, orator and agitator, is entirely unknown. His life is sketched in the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It doesn’t convey the richness of Holland’s journalistic and political contribution to Ireland’s struggle for freedom from Britain in the mid-19th century however.

In his short, intense career, Holland wrote hundreds of thousands of words dedicated to a single aim; the unshackling of Ireland from British rule. Like other nationalists of the period, he was committed to repeal of the Union. Unlike them, he was fired by a fierce opposition to landlordism and campaigned relentlessly on behalf of the agricultural poor.

Holland understood that the system of land ownership existed as a result of colonialism and was unlikely to be overturned by the force of argument. “The English parliament never did anything for Ireland on the simple justice of her claim,” he contended, “The moral our history teaches is all the other way.” To bring about genuine change, armed struggle was inevitable.

Holland’s truculence, in print and on the platform, won him few friends. Aside from antagonising the Westminster political elite, the Protestant Ascendancy class, and members of the Orange Order, he upset other nationalists, and other journalists, with his demands for a muscular response to British rule.

On occasion, his pro-Catholic polemics appeared overtly sectarian and some of his ideas, such as his belief in the racial differences of Saxons and Celts, now seem embarrassing. Yet Holland’s political writings in the years between 1852 and 1863 provided a compelling counterpoint to the prevailing press narrative. He challenged the Ascendancy newspapers in Dublin, the Orange papers in Belfast, and much of the output in nationalist titles, especially The Nation.

Born in Cork city’s Marsh district in 1826, little is known of his parents. A child prodigy, he wrote fluently from an early age and revealed an aptitude for debate, talents which emerged when he attended the Capuchin Friary. Its Superior was the noted temperance crusader Father Theobald Mathew, who founded a society to stimulate debate about the benefits of teetotalism. Holland was an enthusiastic member.

It wasn’t long before repeal of the Union rather than denial of alcohol dominated his attention. In his first job, as a reporter with the Cork Examiner, he covered several of Daniel O’Connell’s repeal meetings. He also witnessed the effects of the Great Hunger in west Cork. During a short period in Limerick city, he worked for the Limerick & Clare Examiner, which was run by two brothers on opposite sides of the repeal struggle. One was a staunch O’Connellite, advocating moral force; the other was a Young Irelander who favoured physical force. Disillusion with O’Connell also led Holland toward the Young Ireland movement.

Holland was influenced by the arguments of its most militant member, John Mitchel, which made his next move surprising. In 1849, aged 23, he joined the Northern Whig in Belfast, whose Presbyterian owner, Francis Dalzell Finlay, opposed repeal. He was, however, committed to the Tenant Right League, a campaign eagerly adopted by Holland. His work impressed Finlay, who elevated him to the editor’s chair when, to quote Holland, “I had only stepped over the threshold of manhood”.

He soon recognised there was limited freedom in editing someone else’s newspaper. So, he launched his own title in partnership with a Belfast printer, John P O’Hara. On 17 November 1852, he proudly presented the first issue of a triweekly newspaper, The Ulsterman, on behalf of “the Catholics of Ulster” who “have no independent organ to represent them.” He pledged that his paper would be “thoroughly liberal”, campaign for the extension of the franchise, and aim to secure tenant rights. His central concern was for the marginalised Catholic population who were suffering “abominable prejudice”.

His Ulsterman journalism proved to be a potent mixture of satire, scorn, and sarcasm. He castigated the English “who have too often maligned and cursed our race” and confidently forecast “the time when Ireland… will yet rise up, great and free and happy among the kingdoms of the world.”

His business acumen did not match his facility with words and O’Hara broke their partnership after just 37 issues because of the paper’s mounting debts. He was saved by a wealthy Belfast businessman, William Watson, whose daughter, Ellen, he later married.

While The Ulsterman acquired a respectable circulation and a decent reputation, Holland combined the roles of journalist and activist. His popularity was such that a rival paper, the Belfast Mercury, praised him as an “able editor” who “has made for himself the high character of an honest and independent journalist”.

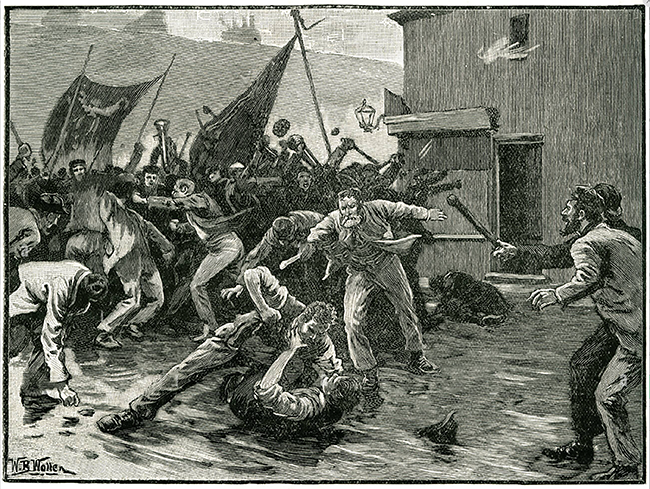

• 1857: The 12 July violence and Belfast riots proved momentous for Denis Holland

The year 1857 proved momentous. First, Holland became embroiled in the controversy which erupted after 12 July violence in which three Catholic teenagers were shot and wounded. It engendered demands among Belfast’s Catholics for armed resistance and Holland attended a meeting of 600 men eager to form a “gun club” to combat “Orange aggression.”

Aware that the move would play into the hands of the city’s Protestant majority, it says much for his standing within the community, and his powers of oratory, that he talked the crowd down from taking such a perilous step. He argued instead in favour of lobbying the Dublin administration to legislate against anti-Catholic violence. To make the case, he produced a pamphlet entitled “The Orange Plague”.

Dublin Castle was listening. It ordered an inquiry after evangelical Protestants staged open-air preaching sessions, that were followed by rioting. Holland, who was one of the witnesses summoned to give evidence, praised the commission for concluding that “the Orange faction” were responsible for the trouble.

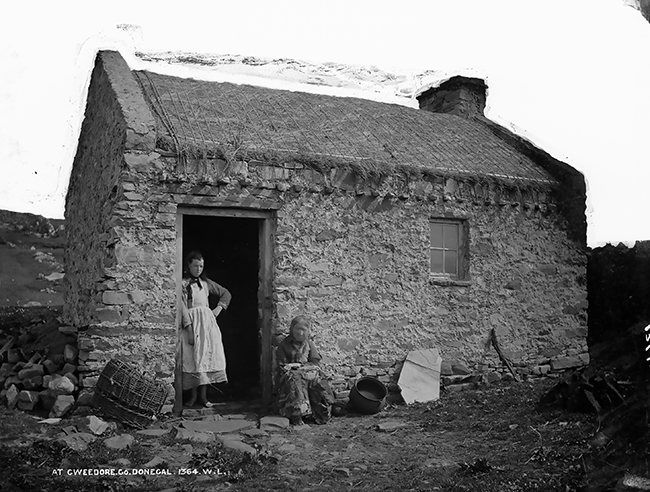

By the time the report was published, his interest was 120 miles away in “the wilds” of west Donegal. He had become a reporter once more to investigate claims by a dozen priests that their flocks were suffering from destitution due to “landlord rapacity”.

In a remarkable series of articles, in which he mocked half a dozen landlords, such as Lord George Hill and Lords Conyngham and Leitrim, he told of their tenants’ miserable living conditions, “human creatures, made to God’s image, crouch and shiver by the little steaming turf heap... where the ragged cow and the little sheep are huddled together with father, mother, and children.”

He also defended the priests on the grounds that they had been “bullied, and coerced, libeled and scandalised” by “corrupt newspaper writers.” They had acted in the wake of protests by tenants about landlords usurping their rights by sealing off mountain pastures in order to make profits by renting them to English and Scottish shepherds. As a result, sheep were either slaughtered or disappeared, leading to the arrests of several tenants suspected of what were called “outrages.”

Holland’s reports, wholly sympathetic to the tenants, were compulsive reading and his intervention was one of the reasons the Westminster parliament set up a so-called “destitution” inquiry. While it was deliberating, Holland moved to Dublin, closed The Ulsterman, and launched a nationwide title, The Irishman.

Among its first articles were Holland’s editorials lampooning the inquiry committee’s official report, a whitewash which cleared the landlords of responsibility for their tenants’ poverty. The result was unsurprising, given that all but one committee member was a land-owner and it fuelled Holland’s disgust for British supremacy.

As an antidote, he advocated the revival of Irish language and culture through Gaelic sports, calling for the creation of a network of parish clubs and a centralised administration. Sixteen years later, his idea became a reality with the formation of the GAA. At the time, according to a fellow journalist, Holland was “the picture of hope and manhood… a man of information and anecdote, which he had the faculty of imparting with fluency… in a most melodious brogue.”

He was a founding member of the National Brotherhood of St Patrick, a front organisation for the clandestine Irish Republican Brotherhood (the Fenians), which advocated armed revolution to secure Ireland’s independence. Holland’s Irishman, as the IRB’s principal platform, published an explosive letter in April 1862 from the prominent Fenian, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, in which he accused the editor of The Nation, A.M. Sullivan, of responsibility for his arrest some four years before.

• Donegal tenants suffered miserable living conditions and destitution at the hand of rich landlords

Sullivan unwisely sued Holland for libel and both suffered from the outcome. Sullivan emerged with a damaged reputation and an award of just sixpence. Holland had to rely on his increasingly exasperated father-in-law to pay his heavy legal costs. Watson also obliged him to sell The Irishman, marking the end of Holland’s major political and journalistic influence.

In 1863, he left his wife and their two sons to go to London, where he acted as correspondent for The Irishman and the short-lived Fenian paper, the Irish People. He was also founding editor of the London-based Irish Liberator, but he fell out with its main fundraiser amid claims that he, a former advocate of temperance, was guilty of excessive drinking.

Matters grew worse when he decamped to New York in 1867. He became a marginalised figure, even among fellow Fenians, and eked out a living by writing inconsequential historical articles for several Irish-American newspapers. For a while, he edited a literary review, The Emerald, in which he adopted a mawkish tone to praise various Irish political figures he had met. He also wrote melodramatic stories, a couple of which were published as novels.

An old acquaintance found the once vivacious and well-groomed editor “stooped, dazed and hungry-looking”. He had become far too fond of drink. At just 46 years of age, in December 1872, he was found dead at his lodgings in Brooklyn. Among the small band of mourners at his funeral were republican exiles, including John Devoy and the poet John Locke.

A sad end, but Denis Holland’s decade of visionary journalism deserves recognition because he identified the reality too many of his peers refused to countenance; Ireland could not win its freedom without fighting for it.

• Note to readers: I have been unable to find a photo, or even a drawing, of Denis Holland. If anyone can help, please email me: [email protected]