13 February 2017 Edition

TK Whitaker - When the legend becomes fact

• TK Whitaker

In 2002, Irish Times readers crowned TK Whitaker ‘The Greatest Living Irishman’

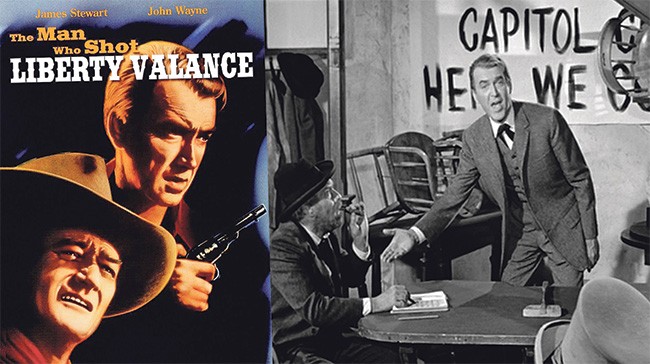

THERE’S A LINE in the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance which goes that when the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

It is uttered by a newspaper man who finds out that the events that made a senator’s career were built on a lie. However, he concludes that, in politics, what is believed is a lot more important than what is true and as the senator (played by Jimmy Stewart alongside John Wayne) is a good man he has no desire to shatter the image, and so he buries the story.

Belief, in other words, makes its own reality.

Myths serve a purpose, although not always for as noble a reason as those of Jimmy Stewart’s senator.

Closer to home, we have quite a wealthy class in the Irish state who have their own foundation myths that have little to do with reality but are no less powerful because of that. And at the heart of them lies the recently-deceased TK Whitaker.

I have no doubt that, in his own terms, TK Whitaker was a noble man. And certainly throughout his decades of public service there was never a whiff of corruption about him. A career civil servant, he was appointed head of the Department of Finance in 1956, leaving in 1969 to become Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland. In 1976, he stepped down from that position and entered into a period of active retirement. He is remembered today as the man who modernised Ireland, in partnership with Seán Lemass.

In 2002, Irish Times readers crowned him “The Greatest Living Irishman”.

The story of the modernisation is this: in 1957 the Irish state was backward and inward-looking, then Whitaker and Lemass came along and the state opened up to foreign direct investment, leading to greater exports and growth, with everything dandy until 2008 but don’t worry because foreign investment and exports will get us back on track.

The problem with this is that the Irish state was a relatively open economy even before 1957. In fact, in 1948 it was one of the founder members of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation, the forerunner of today’s OECD, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The problem was not that Ireland was closed (it was not) but rather its trade was primarily with one country – Britain.

• Jimmy Stewart's character benefited from his local media perpetuating legend as fact

The Economist magazine wrote in 1953 that “the basic problem of Irish agriculture is that it is under-capitalised” – in other words, access to credit for investment was holding back development, and credit policy was being set not by the Irish Central Bank but by a handful of private banks that chose to invest in Britain rather than make credit available here.

This was one of the main sticking points when it came to developing the Irish economy. Irish businesses (in agriculture, services and industry) lacked the access to affordable credit that they needed to expand and diversify. The markets were there (that was the whole point of Ireland’s membership of the OEEC) but the credit was lacking.

The Government’s solution was to sidestep the thorny issue of Irish banks and their refusal to invest in the Irish state and to come up with a plan that would ‘import’ investment through foreign direct investment along with a greater involvement in the public sector in the development of social and economic infrastructure.

Out of this came the short-term solution of offering tax breaks for investment: a quick-fix that morphed into a 60-year economic policy of shortcuts and dead-ends. The main beneficiaries were the indigenous Irish business class that grew out of construction, accountancy, banking and law to service the expansion in foreign factories and public investment.

Meanwhile, the underlying structural problems were left untouched, leaving Ireland with a relatively weak indigenous industrial sector outside of construction.

It turned out that TK Whitaker himself saw these issues in the 1960s and highlighted them but to little avail. There was too much money being made through short-term investments for the game to be changed by something as disruptive as long-term vision. And Whitaker, for his part, was too much the social and fiscal conservative to really push things to where they needed to go in terms of social inclusion and indigenous growth.

It is said that once an idea is given an institutional form it is very hard to dislodge it and the Irish state’s low-tax/construction policy mix is now deeply embedded in the apparatus of the Department of Finance and the Central Bank. This is Whitaker’s true legacy with the myth of the man used to provide cover for those in construction, law, banking and accountancy to continue to benefit from the short-termism of the 1950s to the detriment of the rest of us today.

Whitaker may be their ‘saviour’ but to me he is no more than the man who is supposed to have shot Liberty Valance.