1 December 2015 Edition

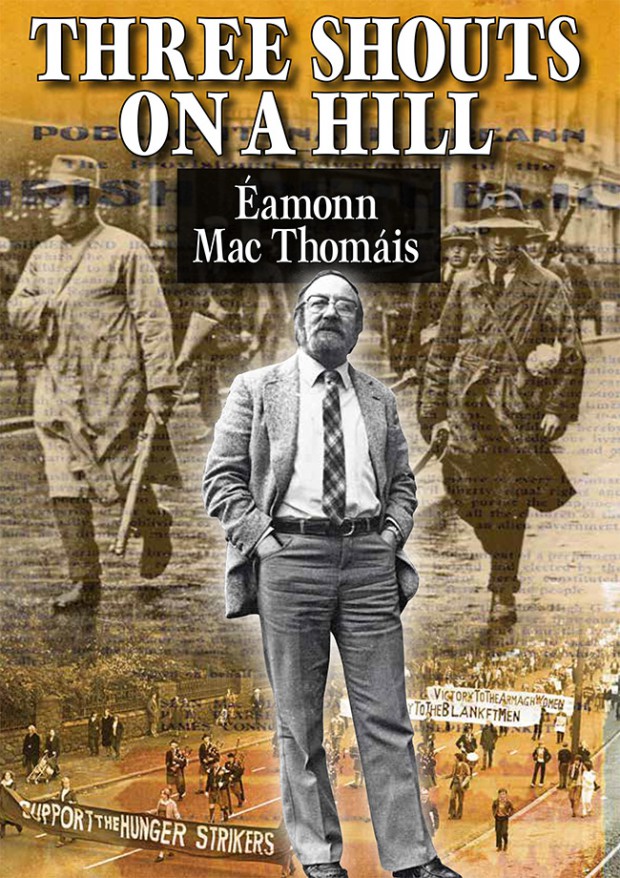

Éamonn Mac Thomáis’s ‘Three Shouts on a Hill’ published in new book

Keyser’s Hill, Published 5th September 1981

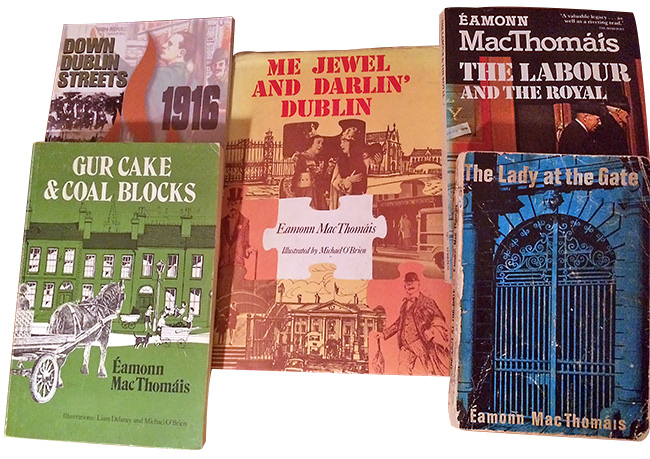

THREE SHOUTS ON A HILL is a collection of essays by the celebrated writer, TV personality and acclaimed historian Éamonn Mac Thomáis. Éamonn’s involvement in the Republican Movement spanned four decades, including periods as Editor of An Phoblacht and as a republican prisoner charged with membership of the IRA.

Three Shouts on a Hill is a series Éamonn had written for An Phoblacht/Republican News in the 1980s, in an era of state censorship, combining his wealth of knowledge of Irish and republican history with commentary on contemporary events almost a decade before the advent of the World Wide Web.

Three Shouts on a Hill is a window into Ireland’s history at a turbulent and tragic time.

It is available from sinnfeinbookshop.com price €6.99 + P&P

• Terence MacSwiney and Tomás Mac Curtain

Keyser’s Hill, Published 5th September 1981

I LOVE EVERY STREET and corner in rebel Cork. Over the years I have got to know a little more about its people, its history, traditions and customs.

I am nearly as well known on the Coal Quay, Curry’s Rock, Blarney Street and Keyser’s Hill as I am in Moore Street and the Liberties. I love to walk along the Coal Quay, chatting up the dealers.

“Come ’ere, boy,” said the big fat dealer. “Are you from Dublin?”

“I am, missus,” I said.

‘Well, boy,” said she, “isn’t this your lucky day? I’ve a pair of blackthorn gentleman’s shoes that I know will fit you like a glove. They’re bran’ new – I got them from the factory last night. I always gets me stuff direct from the makers.”

I put on the blackthorn gentleman’s shoes and they did fit me like a glove. The big fat dealer smiled. “I know the size of every man’s foot,” said she, “by looking at the size of his hands. The shoes is a giveaway at £10.”

“Eight,” said I. “Nine,” said she. “Seven,” said I. “Eight,” said she. “Six,” said I.

“Look,” said she, “this could go on all night. Give us a fiver.”

I gave her a fiver and she gave me back a pound note for ‘hansel’. But she had thrown a trout to catch a salmon.

Before I tore myself away she had sold me four tins of pears, six books, an umbrella, a pair of ear-rings, a necklace and a Mickey Mouse watch. I put my foot down when she wanted her sister to pierce my ears.

“The ear-rings will go lovely with your hearing aid,” she said. “Sure all the young men now wear ear-rings. Ah, go on, boy, you have lovely ears.”

• Éamonn inspects a colour party in Portlaoise Prison

Other voices of ‘Come ’ere, boy’ followed me down along the Coal Quay as I chatted, laughed, and sang Molly Malone with the dealers and people of Cork’s historic marsh.

One dealer made the sign of the cross when I mentioned the names of ‘Duckie in the Wardrobe’ and Andy Gaw.

“Lovely people, sir,” she said. “All gone now.” And her eyes grew sad.

SWANS

I made my way down to Lavitt’s Quay and raised my hat to ‘Old Klondyke’, the great street character of days gone by. I saw a few street characters looking at the white swans swimming up the north channel of the River Lee. They all bid me the time of day.

“I’d love to be a swan,” said one character, “with a lovely long neck and white feathers.”

The swan turned her head to look at her family who were tailing behind.

“Did you see

that?” he said. “She must have heard me.”

He bid me good day and I watched him walk along the Lee’s banks, talking to the swans. A lady in Blarney Street told me that some of the old street characters end their lives in the River Lee and that whenever she crosses the river she always says a prayer for their souls.

Maybe they feel like swans when they hit the water? Wouldn’t it be nice to know that, in their last moments, instead of torment and utter confusion, their minds are full of lovely visions and they see themselves as graceful swans gliding up the River Lee? Old men and women turning into the Children of Lir in Cork’s lovely Lee.

The Marsh is a little republic in itself. So are Blackpool, the Lough, Sunday’s Well, Turner’s Cross and good old Montenotte.

Up beyond St Luke’s I passed the swanky houses of Montenotte and got into the footprints of Robert Emmet, Sarah Curran and the Penrose family, who took in Sarah after her father had thrown her out because of her connection with Robert Emmet.

I waited around Lovers’ Lane until darkness fell, not for romantic reasons but to look down on the lights of Cork City.

What a sight the lights are. City of Cork – city of MacCurtain, city of MacSwiney, city of Tom Barry, rebel city of the Shears brothers – if only your stones could speak, what stories they would tell.

MAYORS

At the turn of every street corner in Cork City there is a plaque, stone, house or wall, each with its own historic story. Mary MacSwiney’s school, Dillon’s Cross, Old King Street, from where the murder gang set out to murder MacCurtain. The street now bears the name of the martyred Lord Mayor, MacCurtain.

I sat in the hallway of the City Hall. On my left-hand side was Seamus Murphy’s bronze bust of MacSwiney; on my right-hand side was its double with the face of MacCurtain. I sat in silence with the two Lord Mayors, tracing in my mind their short lives to the altar of sacrifice for Ireland.

When my spiritual communion was over, I walked out of City Hall with MacSwiney’s words ringing in my ears: “Oh, Cathal, the pain of Easter Week is over now.”

I walked around to the old South Gate by Sully’s Quay, across Cove Street to Tower Street, Quaker Road, and the Red Abbey.

• Sinn Féin TDs Aengus Ó Snodaigh and Gerry Adams with Éamonn Mac Thomáis and Derek Warfield of the Wolfe Tones in May 2002

Everywhere was history and everywhere were friends. “Good day, sir.” “God bless, sir.” “Nice night, sir.” “Very historic, sir.” The ‘sir’ in Cork is like the ‘mister’ and ‘missus’ in Dublin. A sign of respect, a sign of good manners, a sign of friendliness.

The children were fishing and sailing paper boats amid the swans and ducks in the lough. I waited awhile and then moved on across the College Road to the Western Road and Victoria Cross.

I popped down to the County Hall to say a few words to the two ‘Dubs’ looking up at Ireland’s tallest building. Despite all my ballyragging they refused to come home. Nor would they turn their backs to get a fine view of Sunday’s Well and the red and white northside of Cork.

FIRST

• First Shout – to Mickey Devine

My first shout on Keyser’s Hill is for H-Blocks hunger striker Mickey Devine.

It is a shout and a salute to one of Ireland’s bravest sons. Oh, England, if you only had men like Mickey Devine, the cream of Irish manhood, an unpaid soldier of freedom, a man born a socialist republican in the hell-hole of Derry’s Springtown Camp.

I remember Hugh McAteer taking me on a tour of Springtown Camp in the early 1950s. We could not see into the Nissen huts as the smoke from the fires went everywhere but up the chimney. The poverty, the neglect, the barefooted children, the broken men and women. It was one of the worst sights I ever saw in my life, and this is where Mickey Devine was born.

The words you wrote, Mickey, about the other hunger strikers are now your own obituary. No pen could describe it better than yours, Mickey, when, before joining the hunger strike, you wrote:

“There is nothing that any human being values more than life, Every man clings to it with every ounce of strength of his being. To willingly surrender it is acknowledged as the greatest sacrifice any man can make.

“Not only to die but to choose a death which is slow and agonising further serves to illustrate the depths of courage and sincerity amongst the men in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh. What it takes to willingly undergo this ordeal, willingly undergo suffering, none of us can possibly imagine.

“As each day passes, the death shadow of the shroud descends ominously on each of these brave Irishmen as it has done oft times before . . .

“H-Block is a festering sore on the face of Ireland. It, and those responsible for it, must be smashed. We here are helpless. All we have to give is our lives. We simply ask you to do your share and prevent tragedy.”

SECOND

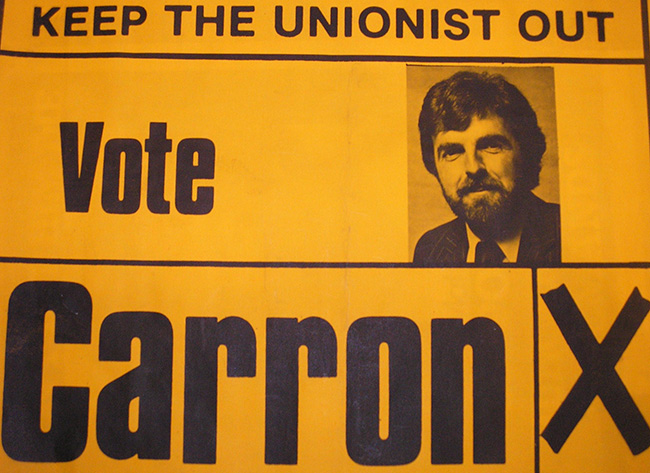

• Second Shout – to Owen Carron's election win

My second shout on Keyser’s Hill is a shout of joy for Owen Carron and his election victory in Fermanagh & South Tyrone.

Read the election result, England. Read it and weep.

The old flag is raised once again with more votes for the prisoners’ man than Mrs Thatcher ever saw. I salute you, Owen, and I salute your election victory speech and your handling of the pro-Brit, anti-Irish TV interviewer.

THIRD

• Third Shout – to John Kelly 'Do your job!'

My third shout on Keyser’s Hill is to John Kelly, the Free State minister.

A few plain words, Mr Kelly. How do you honour the flag you bear?

One part of it is orange: what have you done for the North since you entered the Dáil? What has your party done for the North since they sold it out in 1922?

One part of it is green: what have you done for the people of the South since you entered the Dáil?

Your last speech claimed that the people were looking for too much state help. What in the name of God were you elected for – to sit in the Dáil and draw your big fat salary and eat big dinners at Chamber of Commerce functions and open cow parlours?

A dustbinman is paid to empty dustbins, a roadsweeper is paid to sweep roads; you are paid, Mr Kelly, to work for the people of Ireland.

The men in the H-Blocks are the unpaid soldiers of freedom.