30 June 2013 Edition

The last of the hunters

Ireland’s fishing industry

‘Nobody wanted the Fisheries Minister’s job and there was total ignorance to it. I really think at the time they went into the EC they had no idea what they were giving away’

ACROSS FROM THE PIER in Howth, as the Harbour Road bends seaward past the Olympic Council of Ireland, a small shop tempts the tourist with ice cream, postcards, sweets, souvenirs, trinkets and paraphernalia. Among these can be found the crew of a small fishing trawler.

Packets of four colourfully dressed, thin-bearded caricatures can be taken home for a modest sum and slapped on the fridge as a reminder to buy fish. The irony is that they look nothing like the fishers of today, but it is easier to find toy fishermen in Howth than the real wet-suited variety.

Howth is a seaside anomaly: a port of ghosts and memories, an integral part of the rich history of the Irish fishing industry, yet another place where they used to go to sea, where they used to tell sea stories, where they used to make a living with a tradition that goes back to the time of the Formorians on populated shores.

Fisher people have a great way of expressing themselves. Ask anyone. Fishing and storytelling runs in the blood. In Carna, Ger Folan pulls up the sleeve of his left arm to demonstrate. “It’s in here,” he says, drawing an index finger along a vein. “It’s not just about the money. Or the job itself. It gets to you. Fishing people are a big community; like a family.”

Not anymore. That big community is disappearing and, unlike the capricious mackerel, showing signs that it will never return to the shore for love nor money. The job is getting harder by the day with less money for more work.

• Those with fishing in their blood insist that the industry has a future

In Garinish, Michael ‘Mitey’ McNally, a trawlerman out of Castletownbere like his friend Richard ‘Doc’ Murphy for countless years, is asking his son Cormac what he wants to be when he grows up. “I can’t be fishing ‘cause all the fish is caught,” Cormac says, a sentiment echoed by Doc in his pub in Allihies.

A few years ago, Doc made a tour of the ports. He was rocked by what he saw. His subsequent reasoning is easy to fathom. Until he retired to pour pints, he was one of the catchers, officials in all their guises were the stoppers, and a heady mixture of politics and technology, greed and stupidity brought an impasse between the two.

The fish, meanwhile, hadn’t a chance, while Doc’s prognosis is hardly debated. “The catchers will tell you it’s over. We are the last of the hunters.”

What is debated among fishers and those who regulate and study fishing is the impact of technology.

Overkill is a harsh way of describing what happened after the 1990s with ‘super trawlers’, gil-netting, sonar and the like, but it is a reality now agreed by many including wily old catchers like Doc.

“They started rock-hopping. That was the only safe haven the fish had, but when they went in there that was the finish of it. That was the only place the fish could escape to and they took them. When you see baby fish – seed haddock, seed hake, seed cod, seed monk – that’s the end of that fishery and they were getting all kinds of seed fish.’

• Clogherhead trawlers sit in Howth harbour during the renovation of their home port

Over-fishing only tells part of the story. There is also a cultural element.

Ger Folan is one of a diminishing number of younger fishers still at the game. He started at a young age. “I sold my first box of lobsters for £265; I was only 11. I just loved it. I can’t explain it.” Now he worries for the future of fishing along his stretch of coast in Connemara, where in his lifetime the boats have gradually disappeared, leaving himself and a few others an endangered species. “I don’t know where the next generation is going to come from; children are better educated, there are better opportunities for them.”

Although he has his own small boat, he is restricted by what he can catch and limited by his choice of trawler berths. “The trawlers in Rossaveal are half-Polish, Ukraine and the like and don’t take local lads. You’d look out there on a summer evening and it would be like a small city, all the French lads and Spanish boats.”

For him and many other fishers working the coastline, it’s all about small boats and pots, and large cages for keeping the fish – scallops in the spring, oysters in the autumn, crabs, lobsters and shrimps throughout the year.

“If you don’t go out you don’t get paid. Three or four different buyers come here every month and buy from the pier on a set date with set prices. It fluctuates, goes down a lot in the summertime. In the wintertime, a box of lobsters would fetch double what you’d get in the summertime.”

It is Ger Folan’s honest opinion that as long as there’s a sea and fish in it, people will go fishing. The industry may be in crisis, with fewer boats, longer trips, strict quotas, oppressive laws, fuel increases, elusive fish, irrational conservation and quota mismanagement, but it is not dead. Those with fishing in their blood insist that the industry has a future, despite the incongruity that still exists where Irish fishers are prohibited from landing more than 4% of the EU’s quota.

Kathleen Hayes, a trawler skipper out of Ring before she took full-time to motherhood, advocates a change in the politics of fishing that will benefit Irish fishers instead of treating them like criminals. For more than a decade she has been imploring fishery ministers to take back from the EU what their naive counterparts gave away when Ireland joined the European Community in 1973.

“Nobody wanted the Fisheries Minister’s job; nobody wanted it and there was total ignorance to it. I really think at the time they went into the EC they had no idea what they were giving away.”

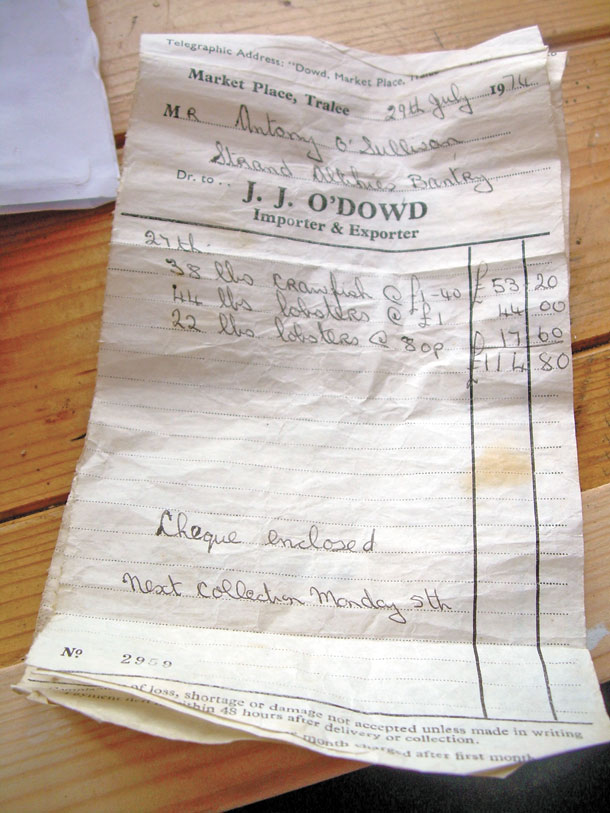

• A pot payment docket in the ‘Good Old Days’

Historically, she is correct but it could have been very different had the 1920s not been so fractious. A carefully-structured policy aimed at developing Irish fisheries was high on the political agenda of the new state. Michael Collins, who had grown up on a farm not far from the sea, at Woodfield between Clonakilty and Rosscarbery in west Cork, knew how important fishing was to the well-being of the people. He believed the sea’s rich harvest could energise coastal communities and stimulate an industry that would benefit the emerging nation after centuries of prohibitive laws. On 11 March 1921, during a Dáil debate on a report by the Fisheries Department, Michael Collins, as Minister for Finance, reluctantly admitted that fisheries was beyond the means of the state. Policy and intricate planning for the indigenous fisheries industry would have to be put on the long finger. It stayed there.

• Hunter: Richard ‘Doc’ Murphy

Five decades later, when the time came for quotas to be dished out, the French and Spanish argued that their slice should reflect the amount of fish being landed by their expansive fleets. Kathleen Hayes says this was to Ireland’s detriment and that the numbers shouldn’t have counted.

“The fact that Ireland didn’t have the boats wasn’t relevant. We had the fish on our shores, we owned the waters but as far as the EC was concerned we didn’t want fishing because we weren’t doing the fishing as we were landing 10 boxes compared to the 20 by the French and the 30 by the Spaniards. The French and Spanish wanted it, they needed it and they showed they were getting it on paper. That’s why today we’ve had such a hard battle to fight for quotas. It’s only now we are showing what we are catching, it’s only now that we can compete.”

She is also cognisant of a terrible fact that has done more to damage the industry than anything else, as the consequence of a repressive colonial past and the negative impact foreign rule has had on an ancient maritime culture.

“We never took fishing seriously because we didn’t eat fish. We weren’t a food country like France because of our history and our famines. Sure, fish was the poor man’s diet. My own kids, they eat fish, but my God the amount of people that don’t eat it!

“If you go to the south of France, you walk along the pier and the boats come in, huge big boats, they tie up alongside the pier and they sell their fish, and there’s all these fabulous restaurants where you can buy cuttle fish and squid and whatever. In Ireland we can’t do that. We have no fish culture, none whatsoever, and it is so sad.’

Back in Allihies, in Doc’s pub, Mitey tells a joke. The lads have been out in the sound fishing for mackerel. A neighbour who is not in the habit of working without reward tells them it was all for nothing. Anthony ‘Batt’ O’Sullivan, a persistent pot man like Folan, retorts that they were out for therapy. The neighbour thinks for a moment. “And what kind of fish is that?”

Up in Howth, David Doyle, a former crabber, is using his experience to take tourists out sea angling. Beshoff’s, on West Pier, is thriving as a wholesale fish merchant and prawn fisher David Price is hoping he is not one of the last of the hunters.

Robert Allen’s book Mackerel and Potatoes: Being and Nothing at Sea, will be out soon.