31 March 2013 Edition

As down the glen one Easter morn . . .

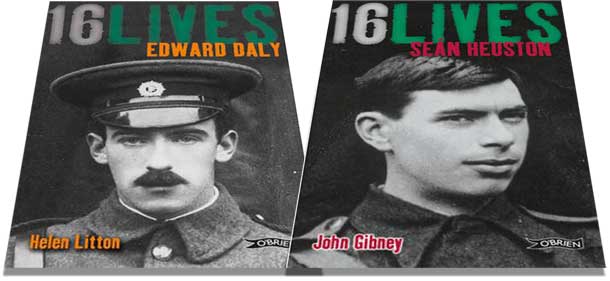

Book reviews 16 Lives Series: Edward Daly, by Hellen Litton; and Seán Heuston, by John Gibney. €11.99 each. Published by O’Brien Press

Daly and Heuston came from contrasting backgrounds, while sharing the same republican commitment. Curiously, Heuston’s north inner city Dublin working-class background has not been highlighted a lot; it should be reclaimed.

THE 1916 Easter Rising holds an ever-evolving and expanding fascination. In military terms it was not a major battle, albeit in a capital city. Casualties were in the hundreds at a time when thousands were being slaughtered every day on the killing fields of Flanders. But politically the consequences of the Rising were huge – epoch-making in the history of Ireland, crucial in the history of the British Empire.

It must be one of the best-recorded events of the early 20th century. We know nearly all the participants on the Irish republican side by name. The opening of the statements by participants in the Bureau of Military History revealed a wealth of detail that is still being mined by historians, including the authors of these two biographies. And there is still much to be discovered, much to be learned. In the pages of these two relatively short books I came upon facts and aspects of the Rising I had not been aware of previously.

And still there are conundrums that will likely never be sorted out. The Military Council’s plans for the Rising did not survive; indeed, it is probable that they were never committed to paper. We know that Joseph Plunkett and James Connolly were the key people in drawing them up. But we can only take educated guesses at the complete plans. And, of course, this is complicated by the fact that the capture of Roger Casement, the loss of the German arms shipment, and Eoin Mac Néill’s disastrous countermanding order meant that the Rising as staged was only a shadow of what was planned.

The wonder is that, despite the enormous confusion of that weekend, men like Edward Daly and Seán Heuston, with hundreds of other men and women in Dublin, turned out and followed the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic into battle on Easter Monday. The disappointment must have been crushing when, after years of preparation, they had to tell greatly-depleted ranks that ‘The Day’ had finally dawned. Yet they persisted and performed remarkable military feats against overwhelming odds.

Barracks in flames

No two commanders in 1916 led more effectively than Daly and Heuston. Daly’s sector was the area from the Four Courts to the Broadstone railway station in the north-west of the city. It was centred on Church Street, where Daly had his headquarters in the Fr Mathew Hall. It was an area of narrow streets, small houses and overcrowded tenements. Here, more than in any other part of the battle, barricades played an important role and there was much hand-to-hand fighting.

• Linenhall barracks

• Linenhall barracks

Daly’s was the only command that successfully destroyed a British Army barracks – Linenhall barracks, which went up in flames. This First Battalion of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers – the Irish Republican Army, as Daly told his men they now were – held out against a massive concentration of British forces right through the week up to the surrender on the Saturday. British troops took out their vengeance on residents in North King Street where they shot at least 15 civilians dead in cold blood, some in the basements of houses where attempts were made to hastily bury them.

Seán Heuston’s Rising was of shorter duration than Daly’s. He was detailed to hold the Mendicity Institution on Usher’s Island on Easter Monday for a few hours to impede British military movement along the Liffey quays while Daly established his position. He held out until Wednesday with a handful of men and only surrendered when his men were actually throwing British grenades back out the windows at their invading attackers.

For such a young man Heuston showed remarkable courage and discipline and commanded great respect from his men. As a key figure in Fianna Éireann he had played a major role in the training and organisation of the Volunteers and preparations for the Rising.

• Barricades played an important role in the battle and there was much hand-to-hand fighting

• Barricades played an important role in the battle and there was much hand-to-hand fighting

Daly and Heuston came from contrasting backgrounds, while sharing the same republican commitment. Curiously, Heuston’s north inner city Dublin working-class background has not been highlighted a lot; it should be reclaimed.

Edward Daly came from a relatively prosperous Limerick family. But their Fenianism led to great hardship. Edward’s uncle, John, had been jailed in harsh conditions in England. His sister, Kathleen, married Tom Clarke, so when the executions came she lost a husband and a brother. The Daly family remained staunch republicans and their home and business in Limerick was wrecked by both the Black and Tans and the Free Staters. One of the saddest episodes in these books is Edward Daly’s mother being struck and injured with a rifle butt by a Free State soldier on a vigil for republican prisoners.

Credit is due to authors Helen Litton and John Gibney for these latest two biographies in the superb 16 Lives series which is edited by Lorcan Collins and Ruán O’Donnell. Beyond the familiar names and photographs, a deeper knowledge of the 16 executed in 1916 will bring a renewed respect for their courage and their ideals.