3 February 2013 Edition

‘To be terrified of your own history is not a good thing’

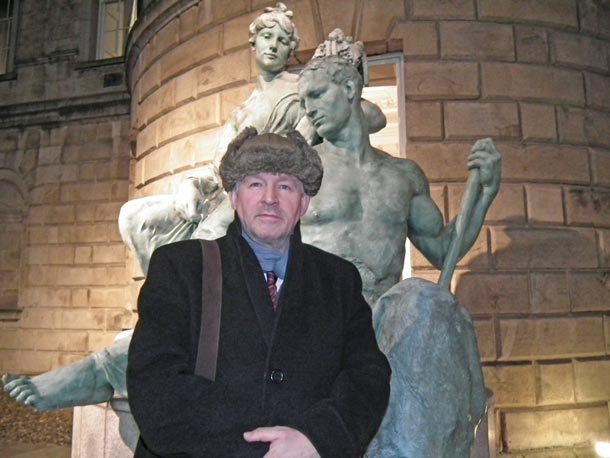

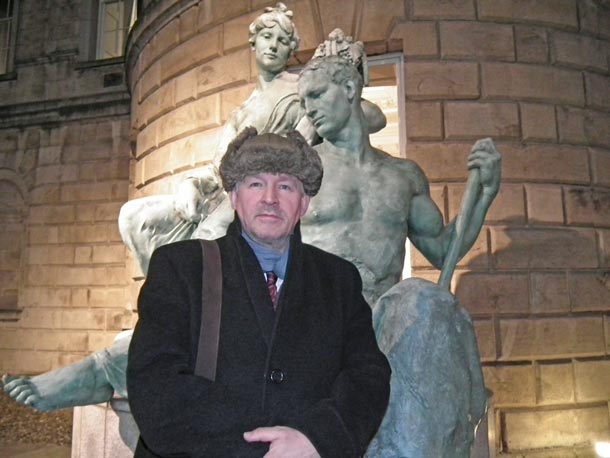

• Artist Shane Cullen

‘These people see themselves as self-appointed guardians. It’s a Catholic, right-wing, Francoist view of things they perceive people should not know about’

ARTISTS need to be noticed but Longford artist SHANE CULLEN hit the headlines nationally in January when Fine Gael councillors tried to have one of his works removed from the Luan Art Gallery in Athlone because they deemed it “offensive” and politically contentious.

Shane’s ‘Fragmens sur le Institutions Republicaines IV’ portrays messages (‘comms’) smuggled out of the H-Blocks of Long Kesh by republican prisoners during the 1981 Hunger Strike. Previously displayed around Ireland and overseas, it went on show in the Luan in November. An official motion demanding its removal was brought before Athlone Town Council in January. An Phoblacht’s MARK MOLONEY caught up with Shane to discuss the controversy and the wider issue of the relationship between politics, censorship and art.

I sit down with Shane in Dublin. He takes off his hat. His long hair which had been a common sight in newspaper photos and on TV in recent weeks has disappeared. “You’ve had some hair cut,” I laugh. “Ah, that’s so nobody will recognise me,” he responds jokingly.

Why had he decided to make ‘Fragmens’? The Hunger Strike and seeing men dying every few months, had a profound effect on him.

“I think everybody in Ireland went through a trauma at that time. It wasn’t until about ten years later that I felt skilled enough as an artist to be able to address such an important event. It took that long for me to feel I could deliver a work that could do it justice and address it properly, in a very public way. I wanted people to recall that time.”

Shane tells me he also wanted to question the huge gaps in the history of the Irish state and political censorship in the later decades of the 20th century in Ireland.

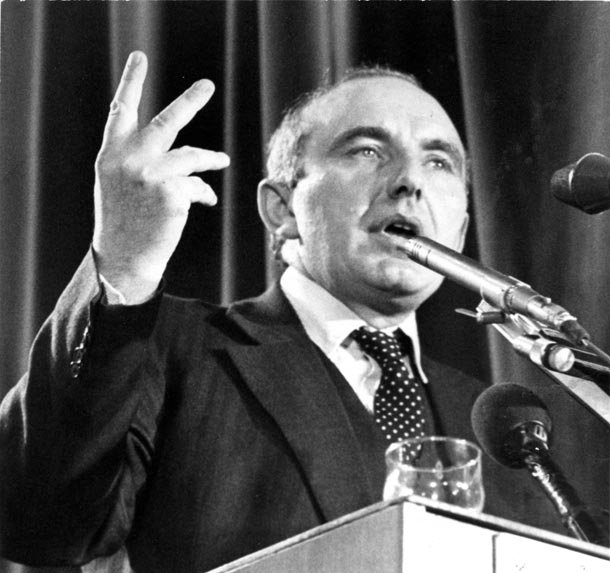

At the launch at the Luan Gallery in November, An Phoblacht Online reported how the infamous former Fine Gael Justice Minister, Paddy Cooney (now aged 81), had actually struck out at one of the panels of Fragmens with his crutch and roared for its removal. Cooney served as Justice Minister from 1973 to 1977, during the time of the notorious Garda ‘Heavy Gang’, which beat and tortured suspected republicans.

An Phoblacht dubbed him ‘Cockroach Cooney’ when he excused cockroaches in the cells and corridors of Portlaoise Prison, where republican prisoners were held. Cooney and the Cabinet he was a member of were so bitter that when the body of Frank Stagg, an IRA Volunteer who died on hunger strike in an English prison in 1976 was repatriated to Ireland, he ordered the Special Branch to hijack it and bury Frank’s coffin in concrete.

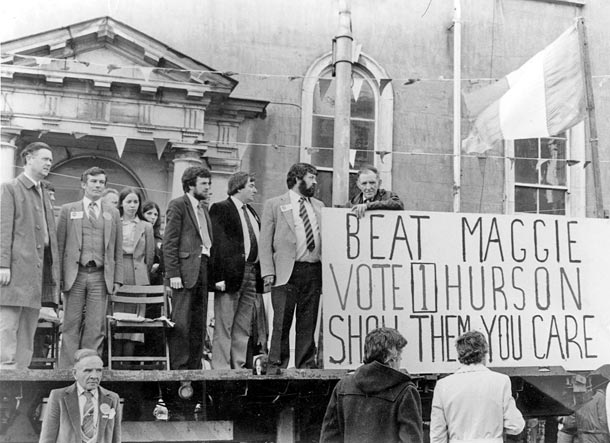

• H-Block hunger striker Martin Hurson stood as a Dáil candidate in Longford-Westmeath in 1981

This January’s council motion calling for the removal of Shane Cullen’s artwork was inspired by the ex-minister’s son, Councillor Mark Cooney, on the grounds that it was “offensive to so many people”. Of the 1,200 people who had signed the guest book at the gallery, only three had made any negative comments about the piece.

“An art gallery is a publicly neutral space,” Shane says, “where people can agree to disagree. So I was a bit shocked that we still have a fear of cultural manifestations that would lead people to censor them, or remove them, or to try keep people from knowing about them.

“It really did shock me when the official motion was made in Athlone Town Council. As an artist I took that terribly seriously and I felt I had to be there at that meeting of the council, not only as the artist who made that work but also as a member of the public whose rights were being infringed by this motion.”

Fragmens had previously gone on display across the globe, in the USA and Europe, but also in towns and cities in the North, including Portadown and Belfast.

“In those places, some people looked at it and I could tell some weren’t liking what they were reading and experiencing,” Shane says, “but no negative reaction was ever directed at me.”

The work was made over a period of five years. Shane worked in various places on the piece, including in a public space at the Old Museum Arts Centre in Belfast. During this period he met former Sinn Féin Director of Publicity Danny Morrison. Danny had been the link between the H-Block prisoners, the Hunger Strikers and the outside world.

“He was there for a play in the theatre upstairs,” Shane says. “I was working in a public space and I was painting the comms very slowly and painstakingly in public. I felt it was important for people to see me doing it. I turned around and suddenly there was this crowd of silent people standing behind me and my hands started to shake as I was painting so I thought I’d have a break and go for a coffee. I turned around and the crowd parted, nobody said a word. People could see how serious I was about this work and the way that I made it. I made it incredibly painstakingly over a period of five years. I somehow wanted to mirror the difficulties the prisoners would have experienced while writing the comms. I didn’t want an easy way of doing it, I wanted it to be really tough.”

While working on the piece in France, Shane says he had to sleep with his legs tilted up in the air so that fluid would return. “I was spending so long standing that my feet began to swell up!”

Shane is pleased that his work can still spark debate after almost 20 years. “ I don’t think that was the intention of the people who tried to censor the work,” he says, “but it has sparked an interesting debate about the role of art and culture.”

• Artist Shane Cullen says he was ‘shocked’ by the official motion to censor his work at Athlone Town Council

So what does he think of those who attempt to censor works they don’t agree with?

“I think there is still this kind of paternalistic sense of responsibility in Ireland. These people see themselves as self-appointed guardians. It’s a Catholic, right-wing, Francoist view of things they perceive people should not know about. We know incredibly little about the Civil War and we’re only starting to see documents and information emerge. Spain has this kind of hidden history to address also. I think the artist’s role is to open up these things and let the air into them. To be terrified of your own history is not a good thing.”

When the motion went before the council on 15 January, Shane was there. Outside, there were dozens of protesters carrying signs reading “Hands off our arts” and “Art is not the problem, politicians are.” Shane says it was great to get such support.

The council heard a counter-motion proposing the Fine Gael motion be simply referred to the board of the gallery. Since the furore, the gallery has reported a big surge in visitor numbers.

During the debate in Athlone Town Council, Fine Gael Councillor Gabrielle McFadden argued that ‘politicially contentious’ art should be removed from publicly-funded art galleries.

“I don’t know how often the councillor goes into the galleries to look at work,” says Shane, “but I think if she came to our own National Gallery and started to remove politically contentious work there would be a lot of blank spaces on the walls.”

He also highlights examples of other ‘politically contentious work’.

“For example, Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ – would that be removed from the Reina Sofía?”

• Former Fine Gael Justice Minister Paddy Cooney

• Former Fine Gael Justice Minister Paddy Cooney

Speaking after the debate in Athlone, Shane referred to a climate where artists seemed afraid to be too outspoken.

“It’s led to a sense that there’s only so much funding for the arts and people won’t get funded unless they behave well in their relationships with decision-making bodies and the authorities,” he says. “I think there’s a certain amount of ritualistic criticism of authority but it’s just for show. I would like to see more artists taking up the deep-questioning, critical role that art should play in society.” He says he would like to see more issue-based works, more “speaking truth to power”.

“Artists don’t have power, not the kind to make the important decisions, but they have a role of questioning how power is deployed in society. If they abandon that role then the public will lose respect for what they do and it’ll become ghettoised and of little significance to people’s lives.”

Finally, Shane says that while some people criticise him, claiming he presents a republican point of view on history, they very rarely refer to Fragmens’ sister work, The Agreement on the Good Friday Agreement.

“That work has not been seen as widely as it should be. The controversy around conflict is much more newsworthy and interesting to the public than a work that is about peace. Fragmens is having a second coming and I think The Agreement will suddenly have a relevance. I do think The Agreement and public ownership of it is important and I would really like them to see that piece too.”