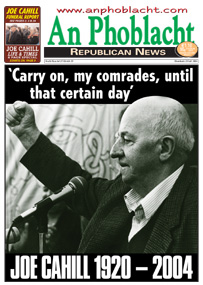

29 July 2004 Edition

Thousands mourn as Cahill is laid to rest

BY MARTIN SPAIN

It might seem strange to say in the context of a funeral, but last Tuesday in Belfast was a great day to be a republican. It is not often that a world famous freedom fighter is laid to rest, so it was understandably a day of pride for the many thousands who gathered to pay their respects to Joe Cahill.

True, there was great sadness for those many people whose lives have been touched by Joe Cahill, but it was also a day for his family to celebrate his extraordinary life. And when we speak of Joe's family, we are not just talking of his immediate and extended family. Because Joe Cahill was also a valued and beloved member of the republican family and of the wider family of West Belfast.

And they came from the four corners of Ireland and from across the seas and oceans to be there to honour a man who had sacrificed so much for the cause of Irish freedom. Even a former Taoiseach, Albert Reynolds, was there to pay his respects.

Joe's family, friends and comrades took turns shouldering his coffin as it was taken from his home in Andersonstown to St John's Church at the bottom of the Whiterock for the funeral Mass. Thousands followed and lined the route, as West Belfast shut down to pay tribute to a man who had devoted his life to defending his community from attack and to spearheading the liberation struggle.

At St John's, Fr Des Wilson spoke of the turbulent times into which Joe Cahill was born in 1920, as nationalists suffered "attacks, the refusal of basic rights and insult from almost every powerful sector in society".

"The history of the years in which Joe lived were in one way a history of horrors," said Fr Des. "But there is another side. Whatever the crisis, there were men and women like Joe and his comrades who would respond on behalf of people who had not created war but too often were victims of it.

"If people were in danger, Joe would not walk away from them. Instead, he would walk into the middle of that danger."

Fr Des pointed out that Joe had never been given a city he could live in which was worthy of his generosity or his courage. Indeed, he said, "that city is still to be created".

Joe, he said, always looked upon himself as a man of action rather than words. "His job was to create the circumstances for all our people to come together around the table and build a new Ireland."

"And he came to believe that the powerful ones of this earth had sometimes to be met with their own weapons. For that he faced and suffered imprisonment and faced and suffered even the sentence of death."

Fr Des recalled that over generations, "the most generous, bravest and kindest of our people have been left unrewarded, imprisoned, tortured, derided, sometimes driven to despair.

Joe "didn't believe in pre-emptive strikes. For him war was a last resort.

"No man or woman should ever have had to believe that such a remedy for bad government was ever needed.

War, said Fr Des, was a necessity forced on people against their choice, often by governments who could bring justice and peace if they so desired.

"For him and for all the people of his tradition, war is a last resort, not a first one, a last resort which can be engaged in only when all other means to obtain justice have been tried and have failed.

"This is indeed a noble tradition among republican people in Ireland. It is also the tradition followed for centuries by faithful Christians. They all believe, if war becomes inevitable, as it may, it has to be tempered by mercy and stopped at the earliest possible moment."

Des recalled that Joe had argued the case for a new Ireland in every country that would have him and even in some that wouldn't, but were given no choice. He believed in reaching out to friends and foes alike.

"It is a pity Joe did not live long enough to see his vision of a new Ireland become a full reality. It is for us who are left to see to it that it does. The achievement of the peace and justice for which he worked is the most fitting memorial we can build to our friend Joe."

Fr Des spoke of Joe's deep spiritual commitment before paying tribute to his wife, Annie, "one of the many courageous women who have shown such courage, endurance, patience and strength when it was most needed".

At the graveside in Milltown after Joe's coffin was lowered, Dublin's Deirdre Whelan chaired proceedings. Gerry Campbell of the National Graves Association led a decade of the rosary before wreaths were laid on behalf of the Cahill family, Óglaigh na hÉireann, republican prisoners, Sinn Féin, Irish Northern Aid, Clann na Gael, Friends of Sinn Féin in the United States, and many more.

Singer Frances Black, a dear friend of Joe and Annie's, delivered a moving rendition of The Bold Fenian Men.

The main oration at Joe Cahill's graveside was delivered by his good friend Gerry Adams, President of Sinn Féin. We carry it here in full.

Tá muid le chéile ag uaigh Joe Cahill. Le chéile mar chlann mór ag faire amach dá cheile. Mar chairde inár gcroíthe, inár n-anamacha, inár bhfíseanna. Le chéile le Annie agus páistí Joe agus Annie. Le chéile leis an phobal is i measc an phobail. Is ócáid mór an tórramh seo, ócáid mór inár saol agus i saol ár strácáilt. Ba mhaith liom buíochas a thabairt do gach aon duine anseo.

Is bhféidir liom a rá gan amhras go mbeadh Uncail Joe sásta scaifte mór mar seo a fheiceáil.

Everybody here and most certainly the people who know Joe Cahill will have a story to tell. Joe was a multi-dimensional person. He was a husband, a father, a grandfather, a great-grandfather, a brother, an uncle, a comrade, and a friend. He was also a story teller and he would delight in all the stories that were told in the wake house and in homes across this island and the USA and in the corridors of the British establishment, as news of his death spread.

Joe lived a long life and it's quite impossible to sum that life up in a few words.

Annie Cahill

I don't believe in eulogising the dead but I do believe in celebrating life and particularly a life well lived - a life spent in struggle and in activism.

Of all of us who shared that life, one person deserves our heartfelt thanks. That person is a wonderful woman, and a republican in her own right, Annie Cahill.

I have a great grá and admiration for Annie.

On your behalf I want to thank her and her wonderful family. I also want to thank the extended Cahill clann. All the in-laws and outlaws, the older people and the young ones, all the grandchildren, great grandchildren, nieces and nephews. And Joe's two surviving direct family members, his sisters May and Tess.

Early memories

I first saw Joe Cahill when I was about 14 or 15 going into the Ard Scoil in Divis Street. Some of you knew him for much longer than that. I am thinking here of Madge McConville, Willie John McCorry, Maggie Adams, and Bridget Hannon.

Joe had the great capacity to work with his contemporaries while relating to much younger people. So when I said that people will have stories to tell, it could be prison stories stretching over the decades, from his time in the death cell with Tom Williams, to Mountjoy and Portlaoise, or New York. It could be stories by his comrades in the IRA, their exploits and difficulties, their trials and tribulations. It could be stories of travels through Irish America, or of Sinn Féin gatherings all over Ireland.

Quite uniquely, there will also be stories about Joe Cahill told by Albert Reynolds, by Tony Blair, by Bill Clinton, and by Colonel Ghaddafi.

I'm very mindful of the fact that in the 1970s, when Joe went back to full time Republican work he was already in his 50's. At a time when most people would be thinking of retirement he was back into a rollercoaster of activism and the difficulties of separation from his family.

He is one, almost the last of that group of people, his contemporaries, who came forward into the bhearna bhaoil in 1969. People like Jimmy Steel, JB O'Hagan, John Joe McGirl, MacAirt, Jack McCabe, Bridie Dolan, Seamus Twomey, Jimmy and Maire Drumm, Billy McKee, Mary McGuigan, Daithí Ó Conaill, Sean Keenan, Seán MacStiofáin, Ruairí Ó Bradaigh, John O'Rawe, and many, many others.

Pain of exile

Joe hated being exiled. He was looked after by good people. But even with dear friends, such as Bob and Bridie Smith, Joe told me that on Sundays he would drive into the Wicklow Mountains and think of Annie, his son Tom and the girls. At times, he told me, he cried to be with them.

He had a great wicked sense of humour and a caustic wit. He was also withering when it came to dealing with people who he thought were failing to do their best.

Championing the peace process

When Joe became active in Sinn Féin he was one of the party's treasurers. He was scrupulous and extremely stingy with party funds. In fact his stinginess was legendary. But his logic was impeccable. If he managed to spend a lifetime in struggle without spending a proverbial penny of republican money, he expected everyone else to spend even less.

Joe was a physical force republican. He made no apologies for that. But like all sensible people who resort to armed struggle because they feel there is no alternative, he was prepared to defend, support and promote other options when these were available. Without doubt, there would not be a peace process today without Joe Cahill. And he had no illusions about the business of building peace. Peace requires justice because peace is more than the absence of conflict.

Joe understood the necessity of building political strength and while political strength requires more than electoralism, Joe spent the recent election count glued to the TV set in his sick room and he rejoiced and marvelled at Sinn Féin's successes right across this island. For him, the cream on the cake of the growth of our party north and south was Mary Lou and Bairbre's election to the European Parliament.

The people's mandate

His big fear was that the governments would not respect the people's mandate. His concern was that the establishment, both Irish and British, would deny and not uphold citizens' rights and entitlements.

Joe knew that for a peace process to succeed it must be nurtured, particularly by those in positions of power. He was not surprised at the explosion of nationalist anger in Ardoyne in recent weeks.

He told me to tell Tony Blair, and I did, that the British Government is failing the peace process. Joe's generation were beaten off the streets of this city for decades by the combined might of the corporate state. In his younger days even Easter commemorations were outlawed. Any dissent from the status quo was banned.

Let those in power note that we are not ever going back to the old days of second-class citizens.

Uncle Joe knew those days were over because we were off our knees and he was proud to havey Blair has said if the process isn't going forward it will go backwards. We have told him in recent times that elements within his own system, particularly within the NIO, are doing their best to subvert progress and to encourage the backward slide.

As September approaches, and negotiations go into a new mode, the British Government has a clear cut choice. Either it stands with the Good Friday Agreement, and builds a bridge toward democracy and equality, or it sides with the forces of reaction, as successive British governments did for decades.

Testimonial function

There's lots more could be said on this issue but today is a day for celebrating the life of our friend. In reflecting on what I was going to say today, I thought back on the last occasion that Joe and I and Annie and Martin McGuinness shared a public platform.

At that event in Dublin, Joe made a wonderful speech. I will finish by letting him speak for himself. I know that notion would amuse him. I have talked for long enough at his graveside. This is in part what he told us that evening. He said:

In his own words

"I have had a long life and a good life. I have had a lucky life and I have had a life that many people have helped me in. And if I started to thank everybody that it was necessary to thank throughout my life we would be here to morning and you don't want that. You want to get on with a bit of craic.

We all have dreams and we all have desires. A few weeks ago I was being released from the Royal Victoria Hospital. As I was waiting to go down in the lift to the ground floor I happened to look out through the window and I saw the best sight ever of the Cave Hill.

I remember looking at the Cave Hill and I remember thinking that is where it all started. I thought of Tone and his comrades and what they said and what they planned to do.

What struck me most was that they wanted to change the name of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter to Irish people. That started me thinking and then I thought of the people who came after them. Emmet and what he tried to do and the message that he left us.

My mind wandered on through the years to the Fenians and one man stuck out in my mind, not a Fenian, but a man called Francis Meagher who brought the flag that we all love, our Tricolour. He said, 'I have brought this flag from the barricades of France and I am presenting it to the Irish nation. Green represents the Catholic, the Orange the Protestant and the White the truce between them'. I hope that one day the hand of Protestant and Catholic will be united and respect that flag.

Then I thought of the Fenians and I thought of the likes of old Tom Clarke and what he had gone through in prison. I remembered that he was the first signatory to the 1916 Proclamation, which says it all as far as we are concerned. Then I thought of the '30s, '40s and what we went through at that time - the struggle we put up then and what we were up against, right through into the '70s.

People have often asked me 'what keeps you going?' I think of Bobby Sands and Bobby said 'it is that thing inside me that tells me I'm right'. That's what drives me on. I know we are right.

I think also what Bobby said about revenge. There was no revenge on his part. He said that the true revenge would be the laughter of our children.

I think of Tom Williams and the last days that I spent with him in the condemned cell. I think of that letter that he wrote out to his comrades, to the then Chief of Staff, Hugh McAteer. He said the road to freedom would be hard and that many a hurdle on that road would be very difficult. It has been a hard struggle but he said 'carry on my comrades until that certain day'. And that day that he talked about was the dawn of freedom.

Just one other remark I would like to make about Tom. It was his desire, as we all talked together when we were under sentence of death, that one day our bodies would be taken out of Crumlin Road and laid to rest in Milltown. The reason I mention this at all is this is what determination does. This is what consistency and work does. I personally thought that I would never see Tom's remains coming out until we got rid of the British but people worked hard at that. People worked very, very hard and we got Tom's remains out. So with hard work it shows what you can do.

I don't want to keep you much longer but I too have a dream. In 2005 we will celebrate the 100th anniversary of Sinn Féin.

I am not saying we are going to get our freedom by then but certainly we can pave the way by then. We can work hard. And hard work brings results.

I have been very; very lucky in the women I have met in my life. I owe a terrible lot to Annie. Never once did she say don't, stop, I don't want any more. She always encouraged me.

Somebody mentioned earlier on did I regret anything. I said no I didn't, except for one thing. My family. That was tough. I often thought of Annie struggling with Tom, my son, the oldest of the family, and my six girls Maria, Stephanie, Nuala, Patricia, Aine, and the baby of the family, Deirdre. They are a credit to her, they have been a support to me and I thank God for people like my mother and Annie.

I will just finish off by saying there are so many people to be thanked for giving me help throughout my life. No matter where I was, if I was in America, in Europe, if I was down the South, I always met great people who give me support. I am asking for that continued support not for me but for Sinn Féin, for the republican movement which is going to bring about the dreams of Ireland, the dreams of the United Irishmen, the dreams of Emmet, of the Fenians, of the men of 1916, the dreams of those who have died through the '30s, the '40s and right into the present day. And I am asking you to continue your support. Whatever little you have done in the past do that wee bit more and we will have our freedom."

Recommitting to struggle

Sin na focail Joe Cahill. Bígí ag éisteacht leis. Déanaigí bhúr ndícheall.

Comrades, we have lost a great republican and a true friend but his inspiration, his life, his vision of a new Ireland, a free Ireland, outlives him.

A lot has changed in Joe Cahill's lifetime, not least because of his contribution.

So let us go from here today recommitted in our resolve to continue our struggle and to carry on until that certain day.