30 November 2023 Edition

Sunningdale agreement was never about equality or inclusion

As we reach the 50th anniversary of the failed Sunningdale Agreement, glib soundbites detract from the wholesale failure of Sunningdale to address any of the causes of the conflict in Ireland. Joe Dwyer explores the reality of Sunningdale Agreement.

• — • — • — • — • — •

In this 25th anniversary year of the Good Friday Agreement, the refrain ‘Sunningdale for slow learners’ received its predictable airing from the usual quarters. The received ‘wisdom’ that the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement could have readily ended the conflict remains a favourite of the chattering classes.

Nearly 50 years ago, on 9 December 1973, following three days of talks between British and Irish government ministers and representatives from the UUP, SDLP, and Alliance Party, a communiqué was issued from Northcote House in Sunningdale Park, Berkshire announcing that a broad agreement had been reached. A power-sharing Executive in the North of Ireland was to be formed, alongside a cross-border Council of Ireland.

The Agreement was endorsed by the SDLP, Alliance, and the majority of MPs in Westminster and TDs in Leinster House. The supposed ‘moderate’ wing of the Ulster Unionist Party, which was anything but moderate, did not reject the proposals but neither did they unambiguously support them.

There was little prospect of Irish republicans supporting the accord and nor was there any effort to sell it. Under the terms of the Agreement, internment without trial continued, border roads stayed closed, and political mobilisation in nationalist areas remained prohibited. The UDR and RUC were left untouched. Sinn Féin remained a proscribed organisation, just as it had been since 1957. Rubber bullets were still being fired wantonly. The brutality of the interrogation centres and the depravity of the prison regime continued unabated.

The Civil Rights Association publicly denounced the SDLP for resiling from a collectively agreed boycott of all public bodies in protest against internment.

Under Sunningdale, the SDLP’s Austin Currie became the new Minister for Housing and Local Government. Currie had been a noted champion of the popular rent-and-rates strike against internment. Indeed, SDLP leaflets had assured participants that “no arrears will be payable” once the strike was concluded. With Currie purportedly advising one audience, “Drink it, smoke it, gamble it. Just don’t pay it”. Accordingly, thousands of households across the North did just that, with homemade notices in windows announcing: ‘Rent spent!’ However, now as Housing Minister, Currie instructed tenants to come off strike, advising, “Payment in full will be required. There cannot be an amnesty. Arrears must be paid.”

This turnaround dealt an effective body-blow to the campaign of civil resistance. By the summer of 1974, the strike was all but over as the popular expression of protest was effectively suffocated.

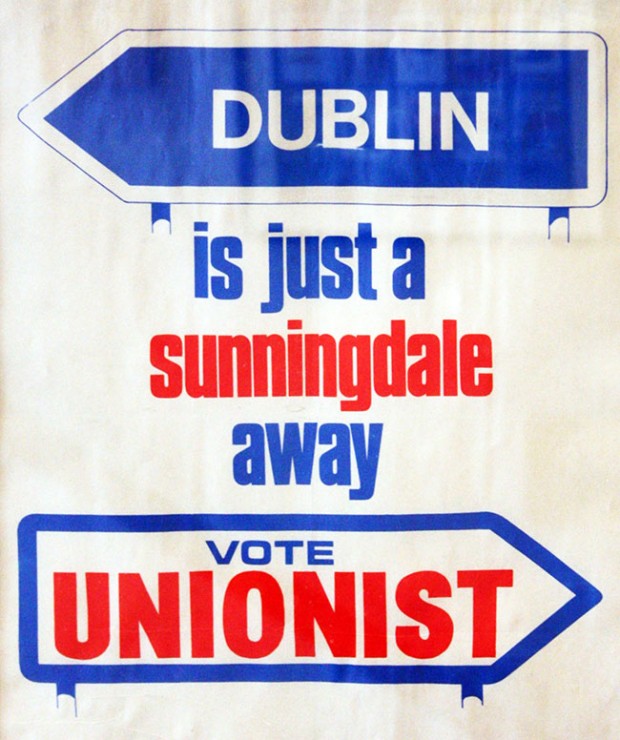

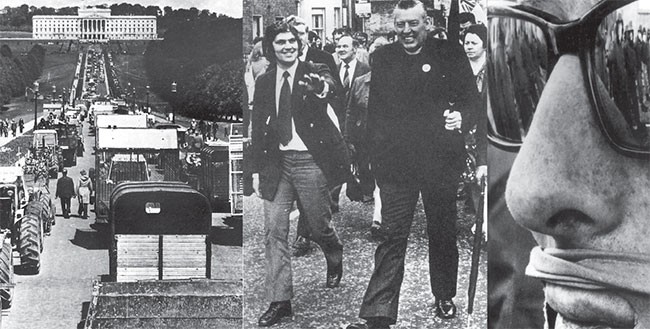

In any event, Sunningdale was ultimately brought down by the combined forces of political unionism and paramilitary loyalism. The February 1974 Westminster election quickly devolved into a plebiscite on powersharing and those Ulster Unionists opposed to Sunningdale decisively came out on top. While this setback may have hobbled the nascent executive, the coordinated general strike organised by the Ulster Workers Council struck the fatal blow.

• The Sunningdale Agreement was endorsed by the SDLP, Alliance, and the majority of MPs in Westminster and TDs in Leinster House

Nonetheless, following Sunningdale’s collapse, few Irish republicans mourned for it. From the beginning, it had been evident that the British state was not seriously seeking to redress legitimate grievances. Ultimately, Sunningdale was never about ending violence. At least not all of the violence as the violence of the state continued. The British Army, and their surrogates in loyalist paramilitary gangs, still sought a military victory over Irish republicanism throughout this period.

The 1973 Agreement gave no concession on security-related matters. Besides the Council of Ireland, it offered little more than ministerial seats to the SDLP. In return, it ushered in a largescale military offensive against republican communities. Indeed, the British government privately briefed that Sunningdale’s greatest success was cross-border co-operation against the IRA. Those at war pre-agreement were still at war post-agreement.

It is telling that today Sunningdale is best remembered not as a cautionary tale or a false start, but rather as a rhetorical counterfactual to be brandished against modern Irish republicanism.

Rather than engage with the material reality of the conflict in the early 1970s, establishment commentators and political opponents prefer to wax lyrical about how ‘slow’ everybody, besides themselves presumably, was back then.

While the late SDLP grandee Seamus Mallon is most often credited with coining the phrase, as with many SDLP positions over the years, he was simply parroting a well-worn establishment line.

The phrase ‘Sunningdale for slow learners’ actually first appeared in a Sunday Independent editorial. It was first deployed, before Good Friday was even written, to characterise the multi-party talks that proceeded the agreement. So, it was never even meant as a judgement on any final document.

It is characteristic of the admonishing tone of the Sunday Independent throughout much of the talks process. Perhaps most infamously demonstrated by the personalised vilification of John Hume during the revelation of the Hume-Adams dialogue.

Besides anything else, the quotation is tactless and offensive. The outdated notion that anyone who disagrees with you must therefore be ‘slow’ should not be celebrated as some great witticism in 2023.

The wording is specifically insulting to those with intellectual disabilities, as powerfully articulated last May by Pauline Tully TD in Leinster House, following Leo Varadkar’s use the phrase, “I do not care what the Taoiseach thinks about my party policies. In fact, I would be worried and wondering where we were going wrong if he agreed with them. However, I care about the choice of words because he has caused deep upset to disabled people, especially those with intellectual disabilities. Language is important.”

Besides being offensive, the ‘slow learners’ assertion has also been criticised by respected political scientists. As the late Rick Wilford articulated, “This remark is as misleading as it is diverting, since the (Good Friday) Agreement is a much more subtle and inclusive bargain than was reached at Sunningdale”.

Obviously, as two negotiated documents, there are broad similarities between the 1973 document and the 1998 document. Sunningdale features a regional power-sharing executive within the six-county statelet, with an all-island dimension. It anticipated a consociational model of local administration with broadly defined ‘identity blocs’, weighted voting majorities, and mutual vetoes.

However, such broad-brush summation overlooks notable distinctions. A key difference is the rights and equality agenda that characterised so much of the 1998 document. It is no accident that the word ‘equality’ does not feature once in the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement. Indeed, during the 1998 talks, the British government routinely sought to substitute ‘equality’ for ‘equity’, preferring the ambiguity of the latter. An exercise that Sinn Féin’s negotiators repeatedly overturned.

The incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into law, alongside other legislative safeguards and protections, marked notable advancements in 1998. Still to this day, the British government is determined to unpick these hard-won gains. Arguably, the greatest measure of their importance.

The powersharing model was also strengthened in 1998 when compared to 1973. Rather than the grand coalition model proposed in Sunningdale, proportionality on the basis of D’Hondt was adopted in Good Friday. Consequently, ministerial posts are held as of legal right and not under the appointment of a British Secretary of State, as they were under Sunningdale. Good Friday also provided for a review of policing and justice structures, the establishment of commissions on Human Rights and Equality, and the rollout of demilitarisation across the North.

The presence of republican and loyalist representatives in the 1998 deliberations was a fundamental divergence. Sunningdale was conceived to endure and withstand an ongoing conflict waging on the outside. Good Friday functioned to bring all parties to that conflict inside the room.

The inclusion of a programme of prisoner release, arguably the truest measure of any end to conflict, demonstrated the importance of such inclusion. Such concerns were never going to be a priority for the SDLP, UPP, DUP, or Alliance. Indeed, at the time, Seamus Mallon had proudly boasted that the SDLP did not have any prisoners.

As the barrister Austen Morgan has noted, unlike Sunningdale, the Good Friday Agreement expressly foresees the possibility of a united Ireland. Under the terms of the 1998 Agreement, statutory emphasis switched from a majority for the union to a majority for unification. Some might consider this to be of little consequence, but something can be gleaned from such deliberate shift in qualification.

Legislatively speaking, under the Constitution Act of 1973, the North would ‘not cease’ to be part of the ‘United Kingdom’ without the consent of the majority. It did not explicitly state, however, that the North’s status would change if there was such a majority. Only that it would not change without a majority. Under the 1998 Act, a United Ireland is specifically envisioned. It is an unambiguous legislative guarantee to give effect to unification if a majority in the North vote for it. What was once implicit is now expressed.

As part of Good Friday, the British government’s standing territorial claim over ‘Northern Ireland’, section 75 of the 1920 Government of Ireland Act, was repealed. In its place, a qualified legislative basis was introduced, limiting the life of the union to the whim of a majority.

The North is the only part of the Union that is inherently detachable. One might even say expendable. Accordingly, any British claim of sovereignty given, without specific reference to consent, is null and void.

• The Ulster Workers Council general strike was the fatal blow for the Sunningdale Agreement

Furthermore, as a result of pressure from Sinn Féin’s negotiating team, the 1998 Act also stated that this new constitutional scaffolding “shall have effect notwithstanding any previous enactment”. Consequently, the 1801 Act of Union and 1973 Constitution Act cannot be upheld as underlying commitments or overriding claims to sovereignty. This inclusion was famously denounced by Ian Paisley, who decried that, “An axe has been taken to the root of the Union!”

The Good Friday Agreement is not a republican document. Ultimately, the Union remains in place.

Fundamentally, it is a compromise. But, as a compromise, it offers an alternative way forward. It is the product of numerous policy documents and submission papers. Reducing such painstaking negotiations and compromises into a game of ‘told you so’ is unedifying. The complicated process of conflict resolution is not a checklist, and it serves nobody to treat it as such.

Power-sharing failed to sustain itself in 1973-74, not because some were ‘slow’ but rather because there were different start lines. The British government had not yet recognised that they could not militarily defeat Irish republicanism.

What took place in Ireland was a political conflict and it demanded a political resolution. One that provided space for all political actors. This was not present in December 1973.

The Good Friday Agreement received popular support, both North and South. Rather than treat politics as the sole reserve of middle aged, mostly middle-class, men in suits, wider civic society was proactively brought into the process in the 1990s. This was a notable step change.

However, just as there were different start lines, there remain different finish lines. While the Union is weakened, Partition remains. The struggle to fully extricate the British state from Irish affairs continues.

But as Gerry Adams once observed, “When I hear some wiseacres saying that the Good Friday Agreement is Sunningdale for slow learners, I think of the wee unionist woman who said recently that it was in fact a United Ireland for slow learners”.

Joe Dwyer, is Sinn Féin’s Political Organiser in Britain