30 November 2023 Edition

Hidden treasures of republican prison history

There were more than 50 different republican prison papers published across 130 years of incarceration in jails spread across Ireland and Britain from 1867 to 1999. Eoghan Mac Cormaic sheds a light on this aspect of prison life from the Wild Goose to the Captive Voice.

• — • — • — • — • — •

In a long and troubled history of political imprisonment, Republican prisoners have used many means to occupy their time, maintain their sanity and morale, and to continue to educate and engage in the wider struggle while ‘faoi ghlas ag Gallaibh’.

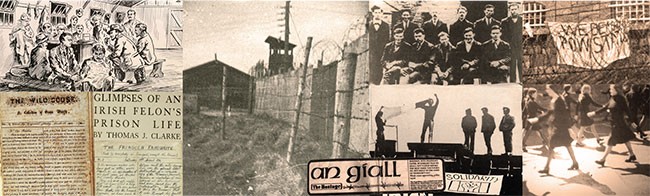

While the most visible artefacts and keepsakes from Irish republican prisoners are ‘handicrafts’ such as harps, crosses, wallets and other items made from leather, wood and even bone, a much less visible heritage of prison life is to be found in journals, magazines, and newspapers produced behind the walls and wire.

Many of these newspapers, created and read within the prisons, existed for only a few issues at most and the majority remain now only as passing references in prison memoirs. In a span of over 130 years however, more than 50 different prison papers existed, sometimes being produced under very difficult conditions and distributed and ‘read’ in very different ways.

The earliest surviving Republican prison paper is a handwritten journal called The Wild Goose, which ran for seven issues on board the prison ship Hougoumont, which in 1867 was the last ship to take convicts to Australia. The editor of the paper was Fenian prisoner John Boyle O’Reilly and the paper contained poetry, history, some politics, and satire. It was hand copied and read aloud to the assembled prisoners during a weekly concert on board.

The Wild Goose may not have been the first newspaper produced by Fenian prisoners however, as some of those on board the ship had previously spent time in Portland Prison where they patiently pinpricked news onto sheets of toilet paper to pass from cell to cell, or in an even stranger ‘newspaper’ where news was scraped onto leather tongues torn from prison boots and furtively passed from prisoner to prisoner.

Tom Clarke recorded in his ‘Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Life’ that he, John Daly, and James Egan used to write each other secret notes, with illustrations, on toilet paper and that this became their newspaper. Then the wily rebel decided to create an even more audacious newspaper. While working in the prison print-shop and under almost constant close guard, the resourceful Clarke managed to liberate letters and font over a long period from the print shop store until he had assembled enough letters to print a complete single-issue newspaper which he titled The Irish Felon and which he shared with his comrades.

Sadly, no copy of this unique tribute to an unbroken spirit remains but his memoir recalls satirising the prison governor and the infamous political defectors Saidléir and Keogh in prose and verse in the publication.

In the aftermath of 1916. prisoners interned in Frongoch produced several newspapers including The Daily Wire, The Daily Rumour, and The Frongoch Favourite. The last of these boasted that it was “Read by everybody in Frongoch except the Censor”. These papers – single sided and handwritten – were pinned to the window of the barbershops in the prison and the news tended to be camp gossip and speculation with some political satire thrown in.

Around 130 sentenced prisoners were held in Lewes Prison after 1916 and they too began their own bilingual paper. Páraic Ó Fathaigh and Tomás Aghas were the respective Irish and English language editors. The paper was called An Bhuabhall (The Trumpet).

Around the same time, a small group of prisoners were interned in Reading Gaol, and with Arthur Griffiths as editor and Seán Milroy as illustrator, An Foraire (The Outpost) was produced. Contributors to the paper included Ernest Blythe and Terence Mac Swiney.

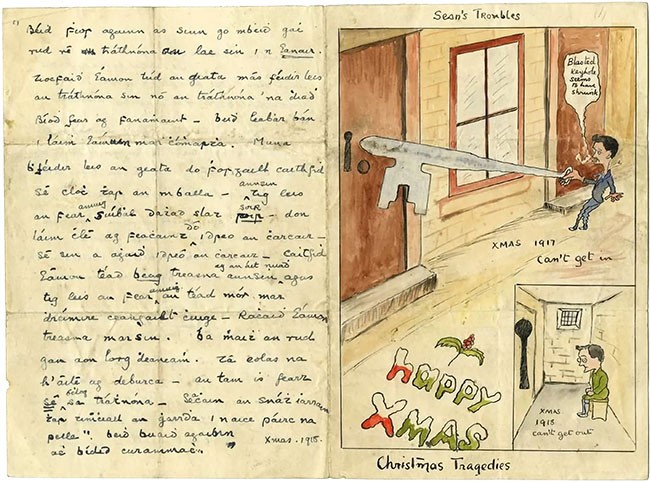

• The Christmas card on which Seán Milroy drew a key to precise scale, that was used to enable the escape of Eamon De Valera from Lincoln Prison in 1919

Milroy’s artistic skills were to be called on a year later while in Lincoln Prison, when he would draw to precise scale a key and lock on a Christmas card from which a real key would be produced to enable the escape of De Valera.

Before escaping from Lincoln, Milroy was also illustrator for that prison’s underground paper The Insect, while around the same time Blythe, in prison once again, would edit a paper in Crumlin Road Jail called Glór na Carcrach (The Prison Voice). Another paper produced in Crumlin Road in those years was called Faoi Ghlas, a title which would be used again in the 1940s and again in the 1970s in Long Kesh.

All of these handwritten publications were read out to weekly assemblies of prisoners in the wings, and political content was more to the fore by now than satire or wing scéal, although such items continued to play a part.

By the end of 1920, internment had been reintroduced and almost 2,000 prisoners were held in two neighbouring cages in Ballykinlar, and also in the Curragh, Spike Island, Derry, Armagh, Belfast, Mountjoy etc. The prisoners were now adept at publishing their papers and titles included Saoirse on Spike Island, and in Ballykinlar one paper from each of the two camps, Barbed Wire and Ná Bac Leis.

The first of these, Barbed Wire, produced in Camp Two was a handwritten paper which contained news and political comment. Ná Bac Leis in Camp One was in a different league from anything produced before.

The prisoners had benefitted from the chaos and backlog created by a parcels strike and smuggled a Gestetner copier into the camp, which of course was seized by the censor. It was successfully spirited from his office and smuggled into the cage where it vanished from sight - and so began a regular printed paper of which around seventy copies were published and sold each month among the prisoners.

During the Civil War, news sheets and papers such as The Book of Cells (edited by Liam Mellows) and The Trumpeter were produced in Mountjoy. In the Women’s’ Prison, Hannah Moynihan produced an issue of The NDU Invincible for her comrades in the North Dublin Union internment camp.

In the now partitioned North, internees were held on the prison ship 'Argenta' and published a paper called The Ship’s Bulletin. That paper was brought to a sudden end when the editor was sent to a punishment wing in Derry Jail for having the audacity to sign his name to a letter complaining about conditions on board the overcrowded ship.

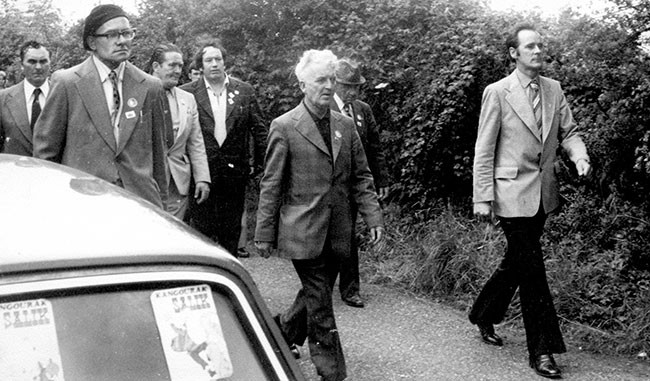

• Bodenstown 1973: Dáithí Ó Conáill (right) was editor of ‘An Timire’ and ‘Saoirse’

Republicans would be imprisoned again during the forties, North and South. The Curragh saw a number of papers in circulation, including Barbed Wire and a paper produced by the Communist Group of internees (including Neil Gould and Mícheál Ó Riordáin) which they named An Splanc (The Spark) in a nod to Lenin’s paper Iskra (also, The Spark).

Papers were also produced in Mountjoy Jail and in Belfast and Derry Jails. Ironically, another Spark, An Drithleog, was produced in Derry Jail although it had no communist leanings whatsoever. While in the 1970s, yet another Drithleog was published, that one in the USA and containing prison news and articles from internees aligned to the ‘official’ IRA.

The longest running paper of the forties which was produced in both Belfast and Derry Jails was Faoi Ghlas. This paper began as a satirical newsletter in English, on multiple typed copies using carbon paper. It then became an Irish language paper under the editorship of Tarlach Ó hUid.

After a break of almost two years, the paper had insulted the Irish dancing teacher in an article and refused to apologise, it reappeared as a handwritten paper – the governor of the jail had seized the typewriter in retaliation against the 1943 escape of Jimmy Steele, Patrick Donnelly, Ned Maguire, and Hugh McAteer. It remained in production as a manuscript paper until 1945.

The 1950s saw the production of another Irish language paper in Crumlin Road, although on this occasion using an English title. The Internee was published by D Wing inmates while across the Circle in A Wing, the sentenced prisoners produced various titles over the course of a long period of imprisonment from the early 1950s until the last of them were released in 1965.

Among the titles adopted were an Irish language paper An Timire (The Messenger) and Saoirse, edited by Dáithí Ó Conáill. The papers were not immune to political strife, with articles sometimes being suppressed for left-wing leanings, presumed indecent content or personalised attacks.

However, the longest and possibly largest period of imprisonment was still to come. It began in 1970 with some arrests and was followed by widespread internment between 1971-75. Sentenced prisoners were held in Armagh, the prison ship Maidstone, Long Kesh, Magilligan, Mountjoy, Limerick, Maghaberry, Portlaoise, and the Curragh, with many more prisoners scattered across English dispersal prisons, and some prisoners held in Germany, Holland and in the USA. Thousands of prisoners were held, often on protests, twelve of them dying on hunger strike and always battling for recognition and improved conditions wherever they were held.

A number of camp-wide and caged-based papers were produced in Long Kesh with titles like Barbed Wire Bulletin, An Eochair, An Fuascailteoir, Ár nGuth Féin (in Irish), and the title Faoi Ghlas making yet another comeback. These papers were often typed and copied and illustrated in colour, with many writers cutting their political teeth in the papers’ collective columns.

The paper Faoi Ghlas was unusual in so far as it had two simultaneous editions, one typed and hand-illustrated inside the prison, with the same content being typeset as a full newspaper and printed and sold outside the prison in Belfast. In Magilligan in the same way during 1976-77, the prisoners produced a paper named An Giall which was written inside, then sent outside for printing as a proper newspaper, and was on sale in Derry and surrounding counties.

The women internees in Armagh in the 1970s produced a paper called Beandando, which provided a platform for satire aimed mainly against their comrades in Long Kesh!

Portlaoise prisoners began a newspaper which was to last for 20 years, An Trodaí, was typed and laid out by the prisoners and then photocopies were made for the different landings through the prison education service.

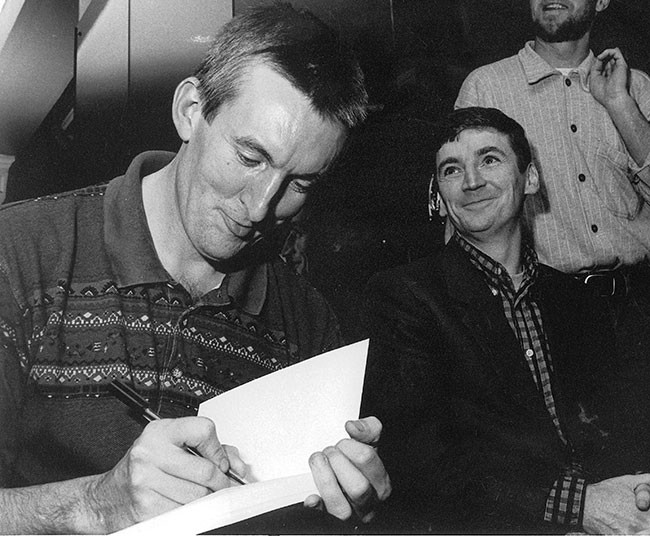

• ‘The Captive Voice’ Editors: Laurence McKeown and the late Brian Campbell at the launch of the book, 'Nor Meekly Serve My Time: The H-Block Struggle, 1976-1981'

When a number of prisoners in Portlaoise formed a Gaeltacht landing, they began a second paper An Réabhlóid, which eventually amalgamated with An Trodaí as numbers in the prisons fell. Prisoners in Portlaoise – and in other prisons – also contributed to the final title in prison paper history, The Captive Voice / An Glór Gafa.

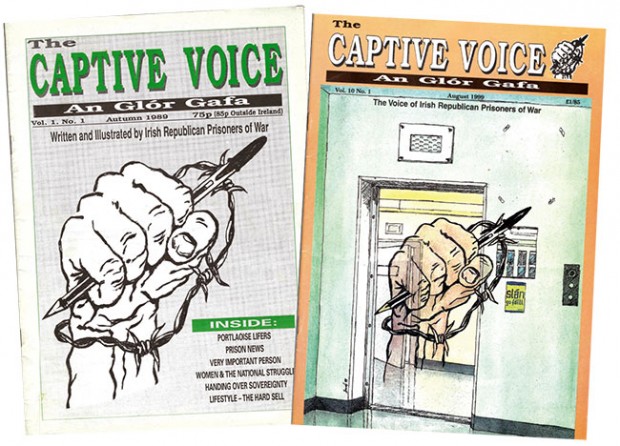

The Captive Voice, produced mainly in the H Blocks between 1989 and 1999 was undoubtedly the most professional of all prison journals. Preceded for a short while by a typed A5-sized annual poetry collection called Scairt Amach, The Captive Voice carried more prose, more analytical and political articles, and occasionally some poetry, crosswords, Irish language articles, and prison gossip/ satire.

The first editor, the late Brian Campbell, became editor of An Phoblacht some years after his release while another member of the original editorial board, Laurence McKeown, has achieved widespread recognition for his prose, poetry, and scriptwriting over the past thirty years.

The Captive Voice, because it was produced inside the prisons but on sale outside in a glossy magazine format, quickly became a collectible item during the ten years of its existence. It was intended to be solely a platform for those physically in prison, but on one occasion, the magazine invited contributions for writers beyond the walls to discuss issues between prisoners and families. In its last issue in 1999, the journal again broke with tradition by inviting Laurence McKeown to pen the final editorial.

Over 130 years span the period between The Wild Goose and The Captive Voice/An Glór Gafa, yet those publications, and the more than 50 others between them, all carried the same message of defiance, of hope, and of comradeship from the men and women who wrote them. They are truly hidden treasures of our republican struggle.