30 November 2023 Edition

Gerry Adams elected president of Sinn Féin

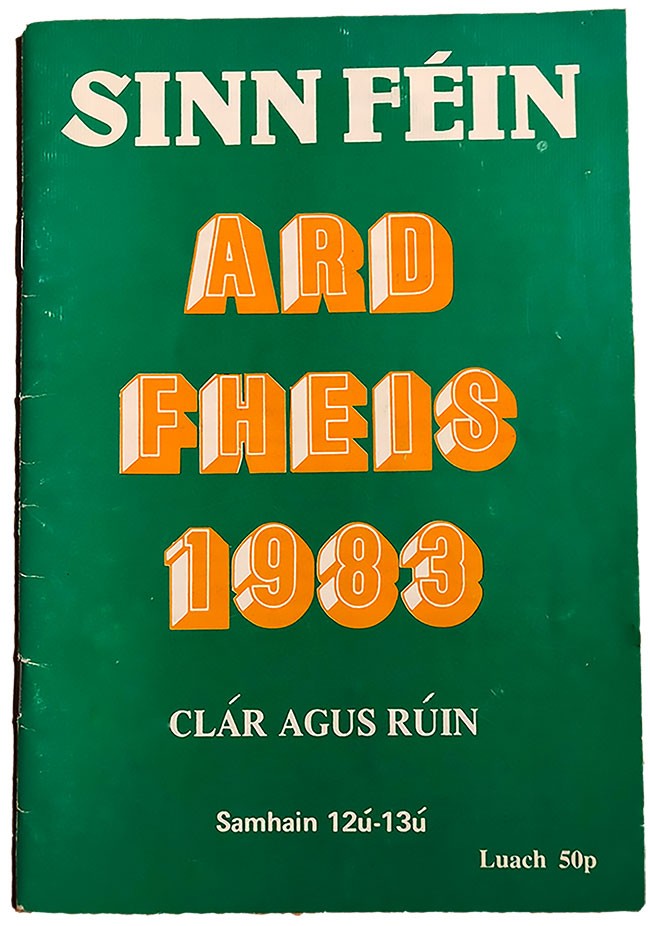

• New Uachtaráin Shinn Féin Gerry Adams and former Uachtaráin Ruairí Ó Brádaigh shake hands at the 1983 Sinn Féin ard Fheis

We asked Jim Gibney to reflect on the 40th anniversary of Gerry Adams's election as Sinn Féin President in November 1983. He talked with two other republican veterans, Danny Morrison and Richard McAuley. Here is Jim’s personal insight, with the input of those two lifelong activists who were there for the key events over the last 40 years.

• – • – • – • – • – •

The first time I heard Gerry’s name mentioned I was walking round the yard in Cage 3, Long Kesh. It was 1973 and I was 18. The memory is of three helicopters in the sky flying over Long Kesh’s airspace preparing to land. Someone in our walking group said that Gerry was in one of the ‘choppers’. He was interned in Cage 6.

Gerry organised education classes in Cage 6 and his advice was to learn about the history of your own country, its struggle for independence, and its heroes like Padraig Pearse, Constance Markievicz and James Connolly.

Back then, republicans were keenly interested in the many anti-imperialist struggles taking place; Cuba, Palestine, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Angola, and the Basque Country. The value of Marxism and socialism were high-profile topics for debate and reading in the Cages of both the internees and the sentenced republican prisoners who had won political status after a successful hunger strike in 1972.

So, it was good advice that Gerry was encouraging republicans to complement their knowledge about struggles by reading about Ireland’s long struggle for unity and independence and to absorb the writings of Pearse and Connolly which covered the national, cultural, and social elements of the struggle.

The next time I encountered Gerry was after his release in 1977. He was in the audience at a meeting in the Ballymurphy Tenants’ Association on the White Rock Road. The meeting was organised by the recently formed Relatives’ Action Committee, set up by relatives of political prisoners in response to the British government’s decision to end political status for political prisoners.

• Long Kesh cages, summer 1975: back row L-R: Seanna Walsh; Gerald Rooney; James Gibney; Brendan ‘Dark’ Hughes; ‘Tomboy’ Loudon; Bobby Sands: front row: Tom Cahill; Tommy Tolan and Gerry Adams

I was a member of the organising Committee. Gerry sat at the back of the hall and didn’t speak at the meeting. I didn’t know he was there until the meeting was over. He left the meeting as quietly as he had been throughout it.

And that is how I experienced Gerry at the many, many, many meetings, at all levels of the party, I have been at with him, since that day in the Ballymurphy Tenants’ Association, almost 50 years ago.

He is of course a remarkable leader, but his presence is ‘soft, ‘discreet’ and ‘encouraging’ of others to speak, especially if it is a meeting of activists or supporters. Even when he is chairing meetings, it is the views of the people in attendance that concern him, not his own views.

His attitude is one of patience, to listen first before offering his opinion which often gathers the strands of other views and thoughts into something cohesive, more focused and more powerful. Adams is a bold and cautious leader, even if that sounds contradictory but his long stewardship of the struggle demonstrates these qualities.

No matter the topic – big or small – he seeks consensus and then proceeds with what has been collectively agreed. Gerry creates space for people, for political views, and especially new ideas to be discussed.

• Gerry Adams and Jim Gibney pictured behind the coffin of Bobby Sands, May 1981

I recall reading a section of his second book, ‘A Pathway to Peace’ published in 1988, in which he explained that, “Peace is not simply the absence of war or conflict. It is the existence of conditions of justice and equality which eradicate the causes of war or conflict. It is the existence of conditions in which the absence of war or conflict is self-sustaining. The Irish people have a right to peace.

“Those who claim to seek permanent peace, justice, democracy, equality of opportunity and stability cannot refute that the abiding and universally accepted principle of national self-determination, in which is enshrined the principle of democracy, is the surest means within which to further those political and social aims and once having achieved them, of maintaining them.”

Those words remain as central to Irish republicanism today as they were almost 40 years ago. In struggle, it is the people that matter most to Gerry. He is a firm believer in the power people have when they combine to achieve an objective local or national. They are at the centre of his political thinking and have been since he first joined Sinn Féin in 1964 and when he campaigned for decent housing in west Belfast and for civil rights.

He combines his belief in people with a meticulous skill for organising, attention to detail and planning and a tried and trusted publicity instinct. Throughout the years of the protest for political status in the H-Blocks and Armagh Jail, Gerry chaired a group overseeing the situation. I was a member of the group. It was a very difficult time for the prisoners and their families and for theHe and I were also members of the National H-Block, Armagh Committee, which organised protests across Ireland in support of the prisoners. There I saw his leadership qualities at close hand, at that seminal and decisive moment in the struggle when the idea of standing Bobby Sands in Fermanagh and South Tyrone was being discussed.

It was a huge decision, a high-risk decision. Even if Bobby did exceptionally well, highlighting the issue of political status, but still lost, the criticism of those who advocated for the electoral intervention could have been overwhelming and damning.

Many people had to be consulted, their views listened to, answers given, and decisions made. Time was of the essence, yet Gerry ensured that all those for and against the idea were met and their voices heard, especially those with reservations.

The outcome – the election of Bobby as the MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone – and subsequently the election of Kieran Doherty in Cavan-Monaghan, Paddy Agnew in Louth, and Owen Carron who replaced Bobby as MP, in the summer of 1981 was a turning point in the struggle.

Ten courageous comrades died, defying British rule and breathing new life into the struggle for freedom. Bobby’s election became the platform that launched a new electoral front, one that was to cause our opponents endless headaches as they attempted to curb our successes, silence our voice, and assassinated our elected representatives through their loyalist proxies.

Sinn Féin stood in the Assembly election at the end of 1982 and won five seats. Gerry, Martin McGuinness, Owen Carron, Jim McAllister, and Danny Morrison were all elected. Gerry and Martin were to lead the party and the struggle for the next 30 years – a formidable pair steeped in activism and street politics.

I was back in prison from 1982 until 1988 and from the H-Blocks watched the party’s growth. I missed the Westminster election of June 1983 when Gerry was elected as the MP for West Belfast and then several months later in November he was elected as Uachtarán Shinn Féin. Gerry, who had been elected MP for West Belfast in 1983, was shot several times the following year.

• Gerry addressing supporters and media after his 1983 election as MP for West Belfast, June 1983

In his first Presidential address, he set the political tone for republicans for the decades that followed, “Sinn Féin’s gain, and the potential for further gains, have not been sufficient to move the British government. We never said or thought it would. There is no magic formula nor short cut in the struggle we have been forced into. On the contrary there is only patient, well planned and sometimes mundane work which will in time create an irreversible thrust towards independence and the restoration of an Irish democracy.

“We do not seek mere territorial re-unification or the merging of the six and twenty-six county states. We seek the unity of all our people in an independent Irish democracy shaped by all its citizens to fulfil their needs. We accept that in a post-British withdrawal situation with Irish democracy restored, we will be bound by the democratic wishes of the Irish people.

“The Protestant people have as much right to a full and equal involvement in this process as any other section of the Irish people. Republican do not seek a sectarian state. On the contrary we seek a secular, or at least a pluralist society. We have more to unite us than to divide us. We offer nothing but equality. We ask nothing for ourselves but equality.

“If Sinn Féin stands on the side-lines separate from and isolated from the people, it cannot hope to attract support for what looks like a vague utopian image of some perfect Éire Nua of the future. The solution is for Sinn Féin to get among the people in the basic ways which the people accept. This means new approaches and difficult and perhaps risky political positions have to be faced by us.”

His years of leadership as Uachtarán saw these ideas made reality. After my release from prison, I returned to the fray. I remember the setback in the Westminster election of 1992, sitting beside Gerry in the early hours of the morning in a room in Belfast City Hall watching his West Belfast seat slip to Joe Hendron of the SDLP due to tactical voting organised by the UDA.

I was devastated but Gerry was philosophical and took it in his stride. A cavalcade was organised for West Belfast, with Gerry in a black taxi to thank our voters. Tom Hartley and I joined it. The response of the people, especially in his home of Ballymurphy, was overwhelming, uplifting, highly charged, and emotional. The people came out in defiant droves to salute us.

I went to a friend’s house and drowned my sorrows in a bottle of whisky. Joe Hendron later remarked ruefully, “You would think they won the election. They organised a victory cavalcade. We didn’t.”

I heard a few days later that Gerry organised a meeting of his electoral team in Connolly House the day the seat was lost. The purpose of the meeting to win back West Belfast, which is what happened at the next Westminster election in 1997. It has been a Sinn Féin seat ever since.

The decision to put Gerry forward for Louth for a seat in the Dáil was again high-risk and bold. Adams topping the poll with almost 22% of the first preference vote was a clear signal of the change to come. His entering Leinster House galvanised and prepared Sinn Féin for the opportunities presented today.

Among the many priorities that Gerry set in his political life, and especially as the president of Sinn Féin, was to strengthen the struggle for a united Ireland, to build a radical republican socialist party, to engage with unionists and Protestants, to encourage women to take up leadership positions, and to promote the Irish language.

His decades-long commitment to gender equality in the party contributed to the process that has resulted in Mary Lou and Michelle becoming our national leaders, with both on the cusp of leading a government in Dublin and Belfast. I think it is particularly satisfying to him that two women are leading the party at this time of great opportunity.

• Gerry Adams, Michelle O'Neill, Mary Lou McDonald and Martin Martin McGuinness, January 2017

A Gaeilgeoir, Gerry was equally committed to promoting the Irish language and was involved in many of the language campaigns and used his personal influence and the power of Sinn Féin to ensure the language was a priority and schools resourced accordingly with public money.

In the late 1980s, Gerry appointed Tom Hartley to lead the party’s engagement with the unionist and Protestant people. Tom invited me to join him in exchanges which have been ongoing. That engagement has been a priority for the party’s leadership for many years and considerable effort has and is going into it.

The biggest challenge that Gerry and Martin as leaders faced was the complexities of creating a peace process from a military stalemate. A process which would lead to an end of conflict but with the potential of realising republican goals to end Partition and reunite Ireland. It was another high-risk and mammoth undertaking.

Gerry chaired what was light-heartedly described as his ‘kitchen cabinet’ to plan this huge project and included the best thinkers in the movement. The successes are there to see in the strides republicans have made. Foremost has been the profile of the campaign for a United Ireland. It is Gerry who chairs the party’s United Ireland Committee, putting into it as many hours now as he did when he was party leader.

Looking back over my experience with Gerry from the first time I saw him at the meeting in the Ballymurphy Tenants’ Association in 1977, he reminds me of a virtuoso composer conducting an orchestra of political activists playing a symphonic song of freedom.

So much of what has been achieved by Gerry was made all the easier by the love and support he got from Colette, his wife and activist in her own right, his family, and from the irrepressible Richard McAuley whose ubiquitous political presence in Gerry’s life could well be described as a revolutionary marriage.

Jim Gibney is a republican ex-prisoner and lifelong activist