24 November 2022 Edition

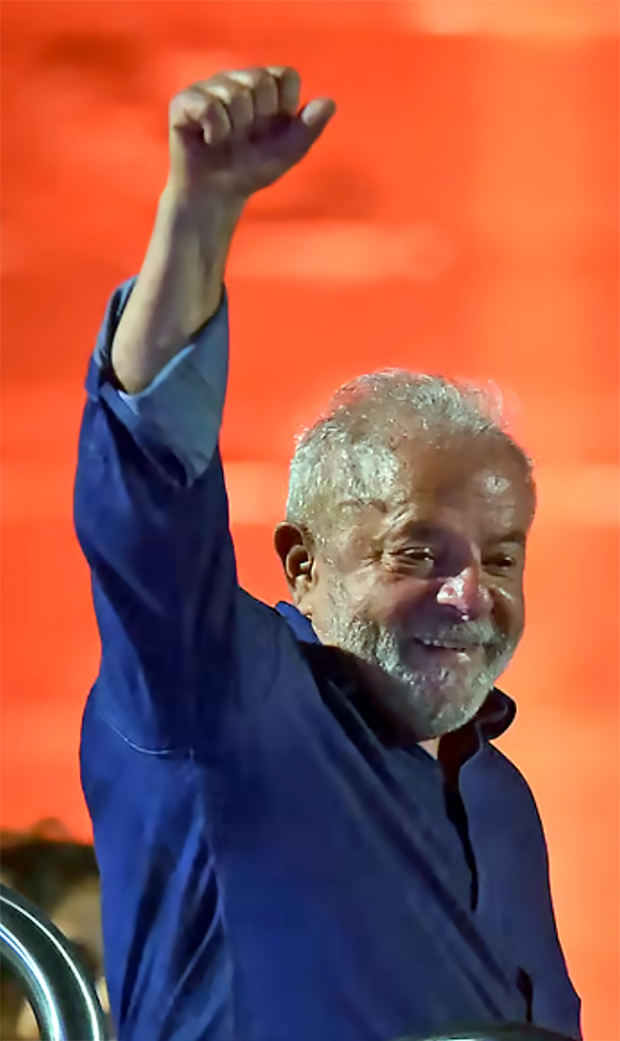

Lula returns as President of Brazil

Luiz Ignácio Lula da Silva was elected President of Brazil on 30 October, beating the right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro by two million votes in the second round. The result was narrow – 50.9% to 49.1% -and the campaign was both dirty and violent.

Bolsonaro-supporting traffic police set up roadblocks in some states to make it to make it harder for Lula's supporters to get to the polls. Seven people were killed in the months running up to the election. In an overall climate of fear and tension, Roberto Jefferson, a prominent political ally of Bolsonaro was arrested at the end of October after inciting hatred against members of Brazil's Supreme Court and then shooting at police officers and throwing grenades at them.

Ironically, it was Jefferson who, in 2005, first set in motion a train of events that are still destabilising South America's largest democracy. Lula's Workers Party (PT) had first come to government two years beforehand, beating the more moderate Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB).

Lula was a former trade unionist and PT played a key role in mobilising the protests that brought down the dictatorship in the 1980s. It consisted of former guerrillas, liberation-theology Catholic laity, environmental campaigners, feminists, and the rural and urban poor. Jefferson alleged that he and a group of other Members of Parliament had been receiving monthly payments to vote for the government on some occasions.

The 'big monthly' (mensalão) scandal led to the sacking and imprisonment of Lula's chief of staff, José Dirceu, a former student leader who had been imprisoned under the dictatorship and freed when a group of his colleagues kidnapped the US Ambassador to Brazil. He was replaced by Dilma Rousseff, another former guerilla who had been imprisoned and tortured by the military regime. Dilma succeeded Lula to the presidency in 2010 when he stood down at the end of his constitutional time on a wave of massive popularity.

Brazil had prospered under Lula, who raised the minimum wage, introduced a rudimentary social welfare system – the family purse (Bolsa Familia) – and massively expanded access to higher and further education.

Maintaining a parliamentary majority became increasingly difficult however and PT resorted to stitching together coalitions by doling out ministries and state appointments to minor political parties in exchange for their support.

In 2012, an investigation into the activities of a money launderer revealed a widespread network of corruption in which businessmen and politicians were receiving kickbacks for inflated payments. Most of Brazil's political parties were implicated in the scheme, but the judge leading the investigation, Sergio Moro, focused increasingly on PT and Lula himself.

Brazil was now mired in recession and the corruption investigation established a causal connection between the two in the minds of many Brazilians. Moro's legal tactics were extremely dubious and some commentators dubbed his strategy as that of lawfare, an overtly political attack on the elected government by judicial means.

Lula was imprisoned, although the cases against him were all subsequently overturned and Moro's investigations also contributed to the impeachment of Dilma, who was removed from the presidency two years into her second mandate. Bolsonaro appointed Moro as his first Minister for Justice, although the two subsequently fell out.

Bolsonaro disastrously mishandled the Covid-19 pandemic which killed almost 700,000 Brazilians. He presided over a record destruction of the Amazon rain forest and a serious deterioration of the public finances.

His populist, macho right-wing message has clearly resonated though with a larger Brazilian audience than many believed existed. Since the return of democracy, Brazil had been mainly governed by the centre-left, PT and PSDB.

Lula chose a prominent PSDB leader as his vice-presidential candidate in this election and reached out to other prominent 'centrist' politicians such Marina Silva and Simone Tebet. Nevertheless, Bolsonaro's vote was much higher in the first round of voting than anyone had predicted. Right-wing Bolsonarist candidates polled well in the elections of the State Governor positions and also now have a large political block in the new parliament. Lula will need all his skills as a diplomat and negotiator to put together a governing coalition.

In Lula’s presidential victory speech, he reached out to all Brazilians – including those who voted for his opponent. Bolsonaro has yet to concede that he actually lost and there is a strong possibility that his supporters may mimic Trump’s actions after his own defeat.

Bolsonaro faces his own investigations into corruption and ties with right-wing militia groups and he will lose legal immunity when he steps down from office. He has strong support amongst rank-and-file members of the police and armed forces and so the possibility of violent confrontation remains high.

Lula is trading on extremely high international good will however, and other world leaders were quick to congratulate him and pledge support to his plans for environmental protection.

• Conor Foley is a Visiting Professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro and has worked on legal reform, human rights and protection issues in over 30 conflict zones