24 November 2022 Edition

The riddle of the rebel

Remembering Erskine Childers 100 years on

“It was Erskine’s sniff that got him shot.” So remarked one who “knew and loved him well”. And perhaps there is truth in such a devastating verdict. For Erskine Childers was often an outsider, even among friends.

Born on 25 June 1870 in London, the second son of Robert Caesar Childers, a translator and scholar, and Anna Henrietta Barton, of Anglo-Irish land-owning stock. It marked a curious start for a revolutionary republican.

Indeed, for the first part of his life, he had been in every respect an establishment subject. A graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge, he worked as a committee clerk inside the British Parliament.

His cousin, Hugh Childers, had served as Secretary of War, first Lord of the Admiralty, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Home Secretary. His best friend from Cambridge, Edward Marsh, was to be the perennial private secretary to Winston Churchill.

Childers himself had even made a bid for a seat in Westminster, standing as a Liberal in Devonport in 1912. Away from parliament, he had served with distinction in the British Army, in both the Boer War and First World War.

Perhaps most notably of all, he penned a best-selling spy novel ‘The Riddle of the Sands’. Later heralded by John Buchan as “the best story of adventure published in the last quarter of a century”.

His first foray into active Irish nationalism came late in life. In 1914, he was approached by a small group of London-based Irish nationalists, led by Sir Roger Casement, seeking a yachtsman to assist with procurement of arms for the Irish Volunteers.

As Darrell Figgis later recalled, “I went to see Mr. Childers at his flat in Chelsea. He told me that Casement had spoken to him fully concerning the project, and that he was willing to help in every way possible, recognizing the risks that were involved, and the necessity for absolute secrecy.”

The Howth gunrunning would become the first significant military operation in Ireland’s 20th Century fight for independence and represented a key milestone on the road to the 1916 Easter Rising.

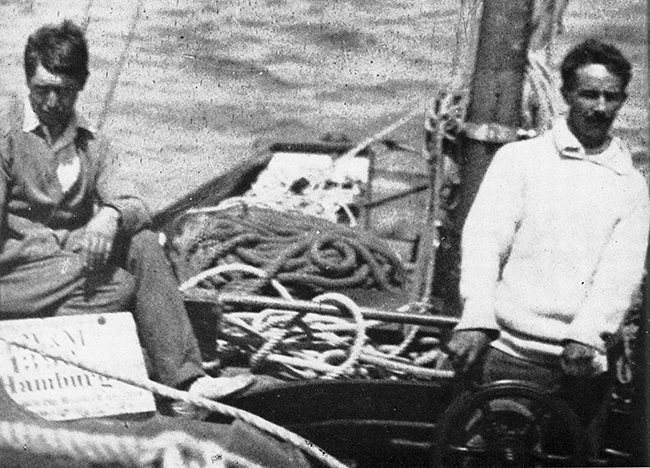

• 1914 Howth Gun running - Childers at the helm of the Asgard and helping land guns in Howth

Indeed, the aftermath of Easter Week and Sinn Féin’s subsequent victory in the 1918 General Election propelled Erskine Childers into the struggle for Irish freedom wholeheartedly. Having crossed this Rubicon, Childers applied the same rigour and determination that defined much of his life.

When he first arrived at Sinn Féin’s Harcourt Street office in March 1919, Arthur Griffith enthusiastically confided to a colleague, “He’s a good man to have, he has the ear of a big section of the English people.”

Within only three years however, the same Arthur Griffith was rebuking Childers from across the floor of the Dáil in the aftermath of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. Bringing his fist crashing down onto a table, Griffith barked, “I will not reply to any damned Englishman in this Assembly.”

To draw such admiration and ire in equal measure was characteristic of Childers. He was in many respects a riddle of a man. Often appearing, to both comrades and critics, as inscrutable and irreconcilable.

Arguably, it stands as a measure of his effectiveness as a political propagandist that he was so loved when inside the fold and so vociferously detested once he stood outside it. Although a liberal by instinct and temperament, Childers penned some of the most radical contemporary thought from the Tan War period.

For he knew the enemy as only one who had once served it could. As a former parliamentary committee clerk, he had spent years drafting and redrafting clauses, amendments, and enabling acts to carry out the functions of Empire. Childers knew the nature of the British establishment intimately and was equally cognisant of the radical, domestic challenges it faced.

For this reason, he was one of the few among Irish republicans to recognise the merit in rallying Britain’s still burgeoning labour movement behind Ireland’s cause.

In May 1919, he contributed a piece to George Lansbury’s The Daily Herald, highlighting reports of British Army mobilisation against striking British workers. He cautioned those on strike to “not forget where and how an army adapted for that purpose is receiving its training and practical experience. Under their very eyes—in Ireland.”

From the pages of the militant newspaper, Childers identified British interference in Ireland as “the ugly face of capitalistic imperialism”, and provocatively asked, “Has Labour forgotten James Connolly, thinker, writer, and Labour leader, who in 1916 for the first time identified national freedom with the cause of Labour in Ireland?”

Recounting Connolly’s subsequent execution, strapped to a chair before a firing squad, he suggested that “a parable for British Labour may be discerned in that incident.”

His anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist critique did not cease here, however. Through an old London acquaintance, and leading member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, R. Palme Dutt, Childers contributed to ‘The Labour International Handbook’ of 1921.

In a chapter dedicated to Ireland, he argued, “The most powerful foe of Labour is capitalistic Imperialism and in Great Britain capitalistic Imperialism stands or falls by the subjugation or liberation of Ireland.”

It is unsurprising that when negotiations with the British finally came about, Childers was selected to serve as secretary-general to the Irish delegation. In fact, it was remarked that Éamon de Valera chose him “knowing that it would be impossible to find in the Dáil anyone so qualified for the position.”

Childers knew, probably better than any of the plenipotentiaries that he now served as secretary, exactly what to anticipate when negotiating with the British. He understood first-hand the need for precision of language when drafting official documents and the pitfalls of inexact terms and open ambiguity.

He was particularly conscious of the need to maintain a united front and avoid the risk of splitting the Irish negotiating team. For this reason, he deliberately elected to ignore his old friend, Edward Marsh, who now sat across from him on the British side, assisting Winston Churchill. It was a decision that hurt Marsh considerably.

Unsurprisingly, having undertaken this personal approach, Childers was considerably frustrated when some on the Irish side began dining and socialising with British negotiators. It was not long before the delegation was split.

A convert of conviction, rather than convenience, Childers was not afraid to plough his own furrow. He could already see the capitulations and retreats that were taking place before his eyes in London.

The British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, later recalled how following the conclusion of the negotiations, in December 1921, “we met Mr Erskine Childers outside, sullen with disappointment and compressed wrath at what he conceived to be the surrender of the principles he had fought for.”

Childers would go on to become one of the most vociferous critics against the resultant Treaty and silencing his voice would become a key objective for the counter-revolution that followed. With the outbreak of civil war, Erskine Childers’ operational control and authority over Anti-Treaty forces became grossly exaggerated by pro-Treaty propaganda.

• Robert Barton, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins Treaty part of the negotiations team returning to London in December 1921

From pro-Treaty pulpits and bulletins, Childers was recast as a sinister spectre who guided the hand behind every nefarious attack and heinous outrage.

On 27 September 1922, with conflict engulfing the country, the pro-Treaty Minister for Home Affairs, Kevin O’Higgins called out Childers personally, in all but name, in inflammatory terms:

“I do know that the able Englishman who is leading those who are opposed to this Government has his eye quite definitely on one objective, and that that is the complete breakdown of the economic and social fabric”.

In truth, Childers’ activity had remained entirely devoted to propaganda efforts, just as it had been prior to the split.

In fact, the closest he came to being ‘a gunman’ was his possession of a pearl-handled, souvenir revolver, a keepsake gift courtesy of Michael Collins, now a bitter opponent.

Tragically, it was the possession of this revolver that ultimately sealed his fate. For when he was arrested by Free State forces on 10 November 1922, the possession of a pistol constituted a capital offence. The following week, he was brought before a secret military court, inside Portobello Barracks. A tribunal deliberately crafted to find him guilty.

That same day, 17 November, four anti-Treaty IRA men, James Fisher (19), Peter Cassidy (21), Richard Twohig (20) and John Gaffney (20), in Kilmainham Gaol, also held for the possession of weapons, were led out of their cells and shot by Free State soldiers.

As O’Higgins later explained to the Free State’s provisional parliament, it was deemed appropriate that the first executions ought to be carried out against rank-and-file men, because:

“If we took, as our first case, some man who was outlandishly active and outstandingly wicked in his activities, the unfortunate dupes, throughout the country, might say that he was killed because he was a leader, because he was an Englishman.”

The following week was to be Childers’ turn.

His conduct prior to his execution was typically brave and courteous. He shook the hand of each member of the firing squad and, once they had taken up position in yard of Beggars Bush barracks, called out to them “come closer, boys, it will be easier for you.” Neither blindfolded nor trussed, he stood with perfect composure.

And so, it was that his supposed ‘sniff’ got him shot. A ‘sniff’ that to some cynics might have suggested a feigned superiority or condescension, but in truth represented a confidence and willingness to stand alone.

The assuredness and self-belief was characteristic of his class, a clarity of vision and certainty of the justness of one’s own beliefs that was instilled by his social background and upbringing. It was an unshakable conviction that rankled those who sought easy refuge and convenient cover.

His written tributes following the untimely deaths of Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, only months before his own untimely end, demonstrate a generosity of spirit and basic goodness that dispels any notion of him being a deranged warmonger or bloodthirsty ‘Englishman’.

While awaiting his execution, he wrote to his beloved wife Molly:

“I die full of intense love for Ireland. I hope, one day, my good name will be cleared in England… I die loving England and passionately praying that she may change completely and finally towards Ireland”.

For Erskine Childers was a riddle of a man. The English-born Irishman who fought for Ireland against England, and who died an Irish Patriot, loving England, before an Irish execution squad.

Here was no fanatic. No zealot. Rather a visionary who saw beyond the bitterness and strife of his own time, who defied the narrow notions and definitions of identity and held fervently onto the hope that, one day, the land of his birth and the land of his heart might co-exist in harmonious friendship - as equals. It is a vision that is still to be realised.

• Joe Dwyer is Sinn Féin’s political organiser in Britain