24 November 2022 Edition

The Mellows I knew

• Nora Connolly O’Brien

This article first appeared in An Phoblacht in December 1932, ten years after the execution of Liam Mellows. Nora Connolly O’Brien, daughter of James Connolly and a revolutionary in her own right, was a close friend of Liam Mellows. She died in 1981 after a life of activism, including supporting the protesting Republican prisoners in the H-Blocks and Armagh Prison up to the time of her last illness.

— • — • —

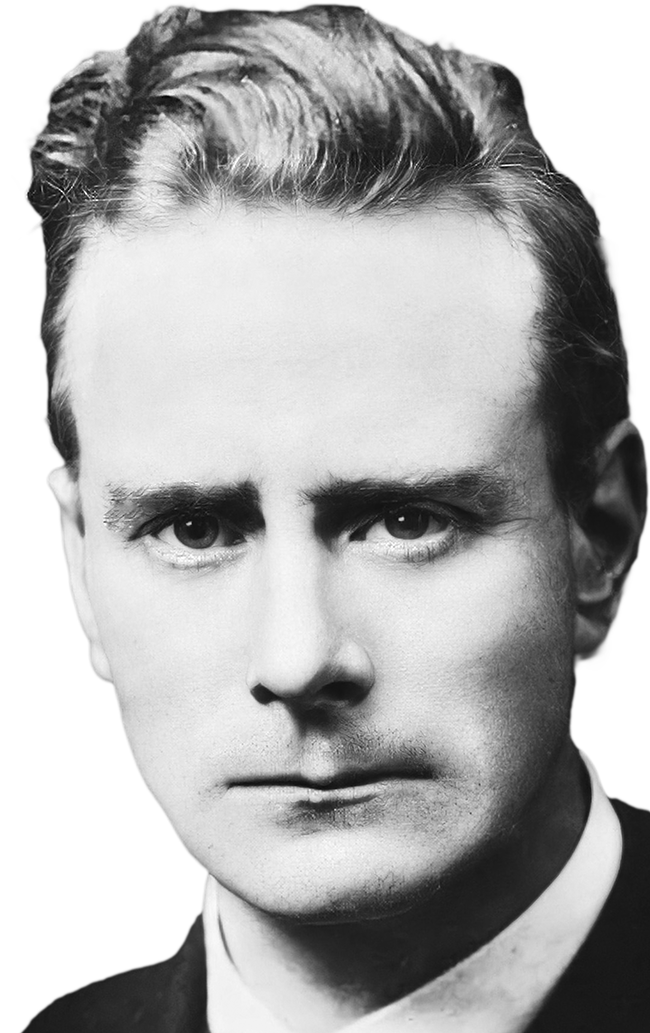

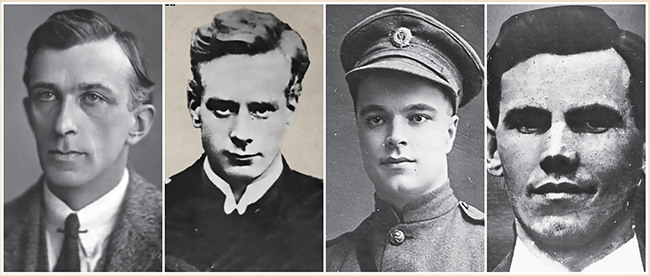

On 8 December 1922, four young men were executed. They were Rory O’Connor, Joe McKelvey, Richard 'Dick' Barrett and Liam Mellows. It is of Liam Mellows, my friend, and for the sake of his memory, I would write.

In days to come, from the long list of Irish heroes, Liam Mellows may well be chosen by the youth of Ireland as their own special hero. They will learn from him how to answer Ireland’s demand for undivided allegiance, for self-abnegation, for service that has in it no taint of self, and that courage, foresight and absolute sincerity which must arm every worker in Ireland’s cause.

He served and was humble in his service, believing that no merit was due to him who did what was right and necessary. Devotion to Ireland was the mainspring of his life, therefore whatever Ireland demanded of him, a big task or a little task, he exerted his utmost in the doing of it – his only thought that it should be well done.

With all his unbounded devotion and singleness of purpose, he was so human, so cheerful, so kind-hearted. He loved a joke as much, if not more than the rest of us, and was eternally youthful in his love of the boyish pranks he would play upon his friends. The best comrade, the best friend, he is eternally enshrined in the memory of those who knew him, and the thought of Liam will forever lie warm in their hearts.

Liam’s service to Ireland began in his early boyhood when he joined and became one of the leading spirits in Fianna Éireann. In those days when the demand for Ireland’s independence was lulled and swamped by the Home Rule movement; when those who believed and hoped for complete independence were considered by the mass of the people, and denounced by their leaders as dreamers and visionaries, if not fools, and were contemptuously called “hillsiders”, Liam was giving every spare moment of his time to the task of winning the boyhood of Ireland to the republican ideal.

Then in his early youth, when others were beginning to think of how best to make their way in the world, Liam threw up all hope of material success and accepted the job of organising the Fianna throughout Ireland. It was not an easy job nor a well-paid job, for he received as weekly wage but a few shillings, and only on a very special or urgent occasion could he take a train; he travelled from place to place on a push bike. But he considered himself generously repaid when his labours resulted in the launching of a new sluagh of the Fianna.

The historians of the future, when seeking the source of the independence movement and its rise from the swamps of the Home Rule movement, will find that the seeds were sown by Liam Mellows in the little groups which he formed throughout Ireland. I would appeal to everyone throughout the country who knew Liam Mellows in those days to write down their stories of him; what he did in their town; the difficulties he had to face and how he faced them – everything they remember of him, political and personal, and send them to someone for safe-keeping so that there will be a record of him who prepared the ground and sowed the seed which blossomed forth into the great independence movement of our generation.

When the Irish Volunteers were formed, the Fianna lent Liam Mellows to be their secretary. And everywhere a branch of the Volunteers sprang into being, there were young men who had been brought into the independence movement by Liam. Boys graduated from the Fianna into the Volunteers; Fianna officers became Volunteer officers.

When the World War broke out, Liam Mellows was one of the first to be arrested and imprisoned for anti-recruiting activities.

And when Redmond demanded that his nominees should have seats on the council of the Irish Volunteers and have a deciding vote in its policy, Liam was one of those who fought and finally caused a rejection of that demand. He was one of those who believed that “Unity is a good thing but honesty is better, and if we can only have unity at the sacrifice of honesty, then it is not worth the price we are asked to pay for it.” It was not possible to believe in the honesty of men who recruited for England when it came to deciding the policy of the Irish Volunteers.

Liam was again arrested and imprisoned, but that did not satisfy the British government. They did not feel safe while he was in Ireland and they deported him to England and confined him to a particular area there. But Easter Week was coming apace and Liam was to be in command in the West. Two Fianna members were sent to England to aid in getting him back. And on Good Friday, when Liam was safe, the Workers Republic came out with a ‘Stop Press’ telling that he was back in Ireland.

Liam was always reticent on the hardships he was called upon to endure while he was being hunted by the British after Easter Week; but there is one story he told which to others in inexplicable, but which Liam and his comrade accepted without seeking explanation. All the time they were being hunted, while they were seeking their way over strange fields and country, they were conscious of a third presence with them – a third man who seemed to lead and direct them and only left them when they reached safety. Liam felt it was someone who in his time had been hunted by the British and who had come to help them. They were continually conscious of him and spoke of him as “the third man”.

• Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Joe McKelvey and Dick Barrett

Liam made his way to America. As usual, he sought no limelight, no personal fame. To work, and to work hard for Ireland was all he asked. He subordinated himself to Ireland, but he refused to subordinate Ireland’s cause to questions of political expediency for the Irish-American leaders. What he felt was right to do he did willingly; but what he felt was wrong no power on earth could make him do. And as a result, he found himself thwarted at every turn. It was not until de Valera arrived in America that his zeal and capacity for work could be exercised.

When he came home, he was back in harness immediately, working day and night at a job that by its nature must have no publicity – Director of Supplies for the Army. But Liam was happy that he was back in Ireland, working for her and serving her by seeing that she was supplied with the sinews of war.

We all remember the Treaty debates and how Ireland’s cause and demand for independence was being lost under a dreadful scramble of words; when so many gods showed their feet of clay; when personal ambitions disclosed themselves; when one-time leaders tore the war-torn nerves of the people by fear and threats; when the one clear speech, thrilling in its simplicity, compelling in its sincerity, was Liam’s. A speech so great and so moving that his opponents declared if the vote had been taken after its delivery the Treaty would have been lost.

His simple undivided allegiance to Ireland made it impossible that he should waver for one instant or compromise her claim for complete independence.

When the Four Courts were attacked, he was one of the men who surrendered and was taken to Mountjoy Jail. There, when the Bishop’s Pastoral was discussed, he declared he could never accept it. His conscience was quite clear on the morality of all his actions, and, as a Catholic, he could not utter lip renunciation to an ideal which his heart would never renounce. That attitude he maintained to the shadow of the grave, and to a fervent, devout Catholic, such as he was, to face death without the consolation of the Sacraments was a greater sacrifice than his life. At the end, that consolation was not denied him.

About two o’clock on the morning of his execution, he got permission to visit a friend. A Free State officer remained at the door of the cell. The friend does not believe that Liam knew at that time he was going to be executed. He said he had come to say “Goodbye”. When his friend asked him where he was going, he said he did not know - he was just being shifted. Some premonition must have come to him just as he was leaving, for he asked his friend to take care of any little things he might leave behind – and mind them for him.

Later that morning in his spirit of cheerful acceptance of all Ireland’s demands, he made his last sacrifice.