24 November 2022 Edition

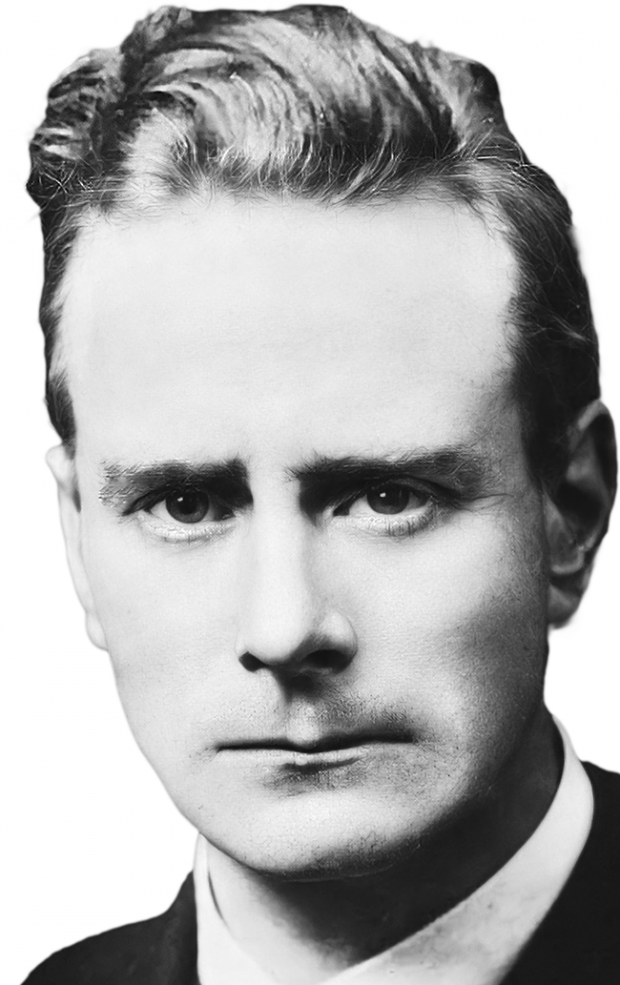

Liam Mellows: the revolutionary legacy

• Liam Mellows

"James Connolly realised that if Ireland were really to be free, it must be owned by the Irish people; that it was little use freeing Ireland from foreign tyranny if, in the course of a comparatively short time, it would fall under domestic tyranny" — Liam Mellows

In ‘The Gates Flew Open’, Peadar O’Donnell’s inspirational memoir of his days as a Republican prisoner during the Civil War, Liam Mellows is described as “the richest mind our race had achieved for many a long day”. Others testified to the magnetism of his personality and his ability to motivate and to organise, as well as his deep thinking and profound commitment to the cause of the Irish Republic.

Nora Connolly O’Brien makes clear in the accompanying article that Mellows had a leading role in the Irish independence movement as a Fianna Éireann organiser, well before the Irish Volunteers were founded in 1913. He was by then tried and trusted enough to go on the first Provisional Committee of the Volunteers. The British regime in Dublin Castle thought Mellows so menacing to their British Army recruiting campaign that he was one of the Volunteer organisers deported from Ireland prior to the 1916 Rising.

Liam Mellows returned secretly to Ireland in time to lead the Volunteers in County Galway during the Rising. It was the largest mobilisation outside Dublin but was only a shadow of the planned force that was to receive the German arms landed in Kerry, distribute them in the West and seize key positions. The failure of the German arms landing and Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order meant that the Galway rising was isolated.

Mellows had a good number of volunteers but few weapons and very limited other supplies. He wished to continue the fight, but his fellow officers prevailed on him to disband the force on Easter Saturday. The previous night he had addressed his men. In a letter to a friend in New York in 1919, he recalled:

“Can I ever forget the scene? Several hundred men drawn up in a courtyard of a castle residence that was our headquarters, at two o’clock in the morning, a weird light cast on the assemblage by several torches of bog deal. They were armed with every conceivable type of weapon, rifles, shotguns and pikes. I spoke to them at length, putting the situation clearly before them, and ended by saying that any man that did not feel he could go further with us could go home and he would not be thought any worse of, he had risked everything in coming out and no man could do more. There was a dead silence for a few minutes then a big powerful countryman, one of the simple, honest, and so many I know here would denigrate as uncouth and ignorant fellows, stepped to the front and said, ‘we came out to fight for an Irish Republic, and now with the help of God we are not afraid to die for it’.”

Mellows went on the run in Galway and Clare and then crossed to the United States where he worked tirelessly for the Irish cause. On his return to Ireland during the Black and Tan War, he was appointed to the IRA’s General Headquarters Staff as Director of Supplies. He was a Sinn Féin TD for Galway East and Meath North. Mellows vehemently opposed the Treaty and his speech against it in Dáil Éireann on 4 January 1922 was perhaps the most impassioned and effective. He asserted that the Irish Republic existed and was a living, tangible thing that was being subverted by the Treaty. Unique in that debate was his strong attack on the British Empire and its whole basis:

“We have always in this country protested against being included within the British Empire. Now we are told that we are going into it with our heads up. The British Empire stands to me in the same relationship as the devil stands to religion. The British Empire represents to me nothing but the concentrated tyranny of ages. You may talk about your constitution in Canada, your united South Africa or Commonwealth of Australia, but the British Empire to me does not mean that. It means to me that terrible thing that has spread its tentacles all over the earth, that has crushed the lives out of people and exploited its own when it could not exploit anybody else. That British Empire is the thing that has crushed this country; yet we are told that we are going into it now with our heads up. We are going into the British Empire now to participate in the Empire’s shame even though we do not actually commit the act, to participate in the shame and the crucifixion of India and the degradation of Egypt. Is that what the Irish people fought for freedom for?”

In a lecture on Mellows in 1972, Peadar O’Donnell stated that while in the USA, Mellows had successfully argued for the inclusion of African Americans and representatives of colonised countries such as India on an Irish solidarity platform. Mellows had known James Connolly and assisted the locked out Dublin workers in 1913.

So, while some have claimed the socialist ideas he set out in his ‘Notes from Mountjoy’ in 1922 came out of the blue, there was clearly a progressive and radical background to his politics. Mellows built on the principles in the First Dáil Éireann’s Democratic Programme, itself influenced by Connolly and Pearse. In a speech in Boston in April 1918, he said the three outstanding leaders in 1916 were Tom Clarke, Pádraig Pearse, and James Connolly. He said of Connolly:

“James Connolly realised that if Ireland were really to be free, it must be owned by the Irish people; that it was little use freeing Ireland from foreign tyranny if, in the course of a comparatively short time, it would fall under domestic tyranny as other countries had done.”

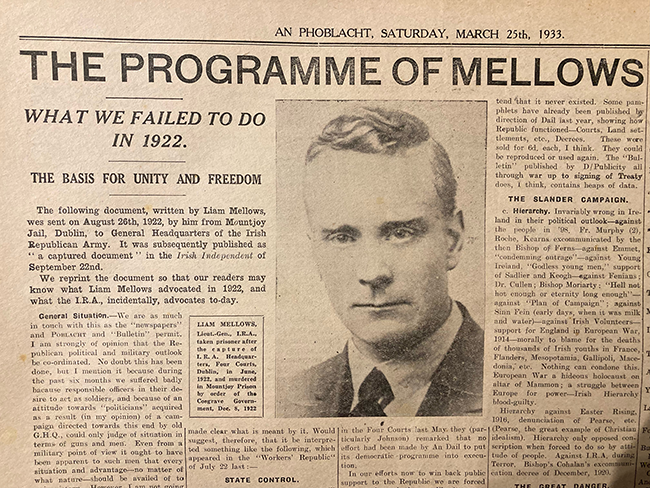

Mellows was jailed in Mountjoy and was there from his capture at the fall of the Four Courts in June 1922 to his death in December. In prison, he had some time to begin formulating thoughts that he had been developing on the Irish Republic as “a People’s Republic”. Some of this was published in the ‘Workers Republic’ on 22 July 1922. He was encouraged by fellow prisoners to elaborate on this in a memorandum to the IRA Executive outside.

He set out what he saw as the political reality:

“In our efforts now to win back public support to the Republic we are forced to recognize - whether we like it or not that the commercial interest so-called money and the gombeen man - are on the side of the Treaty, because the Treaty means imperialism and England. We are back to Tone - and it is just as well - relying on that great body, ‘the men of no property’. The ‘stake in the country’ people were never with the Republic. They are not with it now and they will always be against it - until it wins. We should recognize that definitely now and base our appeals upon the understanding and needs of those who have always borne Ireland’s fight.”

Mellows then sketched a socialist programme:

“Under the Republic, all industry will be controlled by the State for the workers’ and farmers’ benefit. All transport, railways, canals, etc, will be operated by the State - the Republican State - for the benefit of the workers and farmers. All banks will be operated by the State for the benefit of industry and agriculture, not for the purpose of profit-making by loans, mortgages, etc. That the lands of the aristocracy (who support the Free State and the British connection) will be seized and divided amongst those who can and will operate it for the nation’s benefit.”

These notes were captured by the Free State authorities outside the prison and were immediately published and presented as ‘Communistic’, using scare tactics to falsely present them as a threat to personal property, businesses and small farmers. This was worked into the vicious anti-Republican propaganda that escalated in October 1922 when the Free State government gave further Emergency Powers to its Army, with court-martials and the death penalty for possession of weapons, and when the Catholic bishops issued a trenchant anti-IRA pastoral.

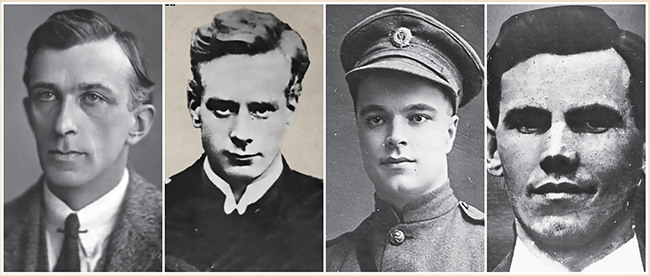

• Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Joe McKelvey and Dick Barrett

The culmination of the Free State counter-revolution was the prison execution policy which began with four Dublin IRA Volunteers on 17 November after ‘trial’ under the new laws. The Free State government went even further with the execution of Liam Mellows, Rory O’Connor, Joe McKelvey and Dick Barrett – there were no charges and no trials because the government admitted openly that this was an act of reprisal. The IRA had shot dead Seán Hales TD, who was also a Free State Army officer, following an order from IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch who had warned that any TD who voted for the emergency powers would be held to account. The four prisoners in Mountjoy had nothing to do with this order or with the killing of Hales, but they were chosen to be executed in an act of revenge.

In the early hours of 8 December 1922, Mellows and his three comrades were taken from their cells to another part of the prison where they were told of their impending deaths. He had time to write a few last letters. In one of them, he wrote:

“I have no regrets, for the future of Ireland is assured. The Republic is assured and before long all Irishmen, including those now unhappily in arms against the Republic, will be united against Imperialist England – the common enemy of Ireland and of the world.”

• Mícheál Mac Donncha is a Sinn Féin Dublin City Councillor