27 January 2022 Edition

Warriors of patience and time

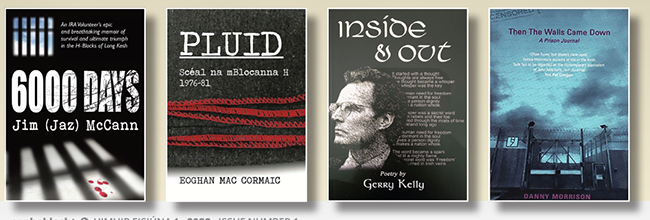

n as many months towards the end of last year, six former political prisoners launched books detailing their prison experience and the years spent in the struggle for freedom – as IRA volunteers on active service on the outside and the inside of prison.

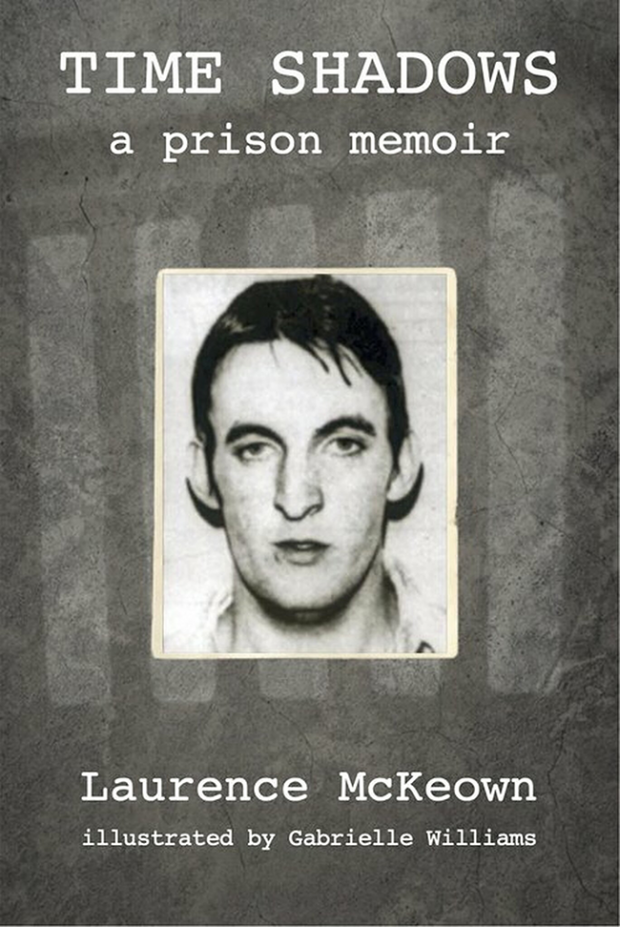

They were: Jim McCann’s ‘6000 Days’; Seamie Kearney’s ‘No Greater Love’; Eoghan (Gino) Mac Cormaic’s ‘Pluid – Scéal na mBlocanna H 1976-81’ (which will be released in English in April 2022); Gerry Kelly’s poetry collection, ‘Inside and Out’; Danny Morrison’s 'Then the Walls Came Down', and Laurence ‘Lorney’ McKeown, ‘Time Shadows – a Prison Memoir’.

All of the prisoners served time in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh and Gerry Kelly also spent many years in various English prisons.

Lorney McKeown spent 16 years in jail; 1,621 days naked in a prison cell, 1,079 days without washing, and 70 days on hunger strike.

And all of the time on protest, he, along with hundreds of other political prisoners, experienced institutional torture and abuse at the hands of prison guards and the prison system including the women on protest in Armagh Jail. These included governors, doctors, senior civil servants at the Northern Ireland Office and at the very top in 10 Downing Street, Maggie Thatcher approved of and sanctioned the abuse of prisoners.

Reading Laurence’s book and Jaz McCann’s, which I reviewed for the Bobby Sands Trust website, I was filled with anger at the casual brutality the prisoners experienced.

A former political prisoner myself, I know the feelings of fear expressed in both books when a prisoner comes face-to-face with prison warders and an implacable administration.

However, there is no comparison between my experience of occasional assault by a small number of prison guards, while I was fully dressed, and to what is chronicled in Lorney and Jim’s books.

The brutality was orchestrated, prolonged, daily - sometimes hourly, systematic, planned but occasionally random.

It was psychological terror with a political purpose – to break the will and spirit of the political prisoners in the H-Blocks and Armagh and force them to accept a criminal status and that the cause of Irish freedom was a criminal enterprise with repercussions for the overall morale of the struggle and how the struggle would be perceived internationally.

It struck me reading the books that the British government has a legal case to answer for its brutality of the prisoners in the same way that the Irish and unionist governments and the Catholic Church had a case to answer regarding the sexual abuse of children in various institutions including the ‘Mother and Baby Homes’.

One of the north’s leading solicitors, Padraig Ó Muiri, is challenging the treatment of the political prisoners, based on the findings of the ‘Report of the Independent Panel of Inquiry into the Circumstances of the H-Block and Armagh Prison Protests 1976-1981’. That report was commissioned by Coiste na nIarchimi which provides services to former political prisoners.

Lorney, now an academic with a doctoral thesis, is a writer, an accomplished author, poet, playwright, and filmmaker. The memoir is written in a matter-of-fact, chronological style, where an economy of words conveys the emotional power of the story from the time when Laurence, from an ‘idyllic, innocent and rural background’, joins the IRA in 1973 until he lapses into unconsciousness on his 70th day on hunger strike in September 1981.

Lorney writes:

“I can recall the moments, good and bad, but I know I’ll never be able to fully capture the strength of emotions as I felt them in those moments, despite the fact that I can still break into tears of laughter, or feel rage or pride, at their recollection.”

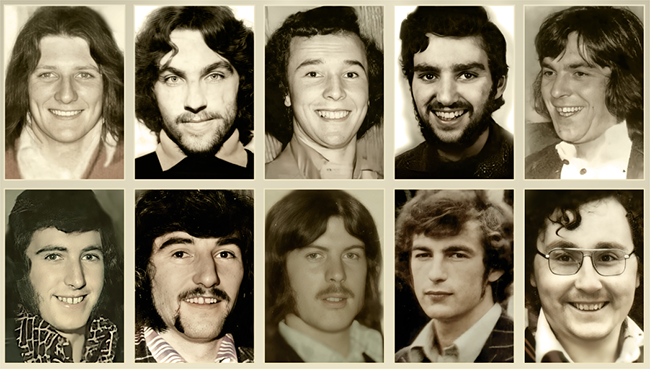

The first four hunger strikers are dead - Bobby Sands, Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh and Patsy O’Hara - and have been replaced by Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kieran Doherty, and Kevin Lynch.

Laurence is in communication with Brendan ‘Bik’ McFarlane, the O/C of the prisoners, seeking permission to join the hunger strike. He says:

“It’s difficult to describe the feelings in the Blocks, or put into words the depth of strength and determination we felt. We had adopted the consciousness of an army at war and our battle was with every manifestation of the system and its administrators, especially with the guard who opened and closed our doors. We were steeled for the battle.”

And what an epic, heroic battle it was. It is an awesome, awe-inspiring story of resistance and endurance by highly-motivated political prisoners.

Lorney received a communication from the IRA’s Army Council, “Comrade, you have put your name forward for the hunger strike. Do you know that this means you will most likely be dead in two months? That means, comrade you will be no more. Reconsider carefully your decision.”

Although he said he hadn’t expected the communication and the words did startle him, especially “seeing my ‘death’ written in black and white appeared very stark, but it didn’t cause me to rethink my position. My earlier examination of the situation had been done seriously and responsibly. I was ready to go ahead.”

And when his father and Mary, a close friend, pleaded with him not to go on the hunger strike, he remained “ready to go ahead”. Laurence wasn’t callous with his family or his friends in carrying on with his hunger strike and the book reflects the emotional turmoil he was in and the feelings he had for his parents and family.

The Hunger Strikers: Bobby Sands, Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O’Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee and Michael Devine

And these are reflected in his relationship with his mother.

When the judge was sentencing him to life in prison, he asked was there anyone in the courtroom who wanted to say anything about the ‘defendant’.

His mother, quiet and very soft spoken, on her own, in the alien surrounds of police, warders, and the court, stood up and said, “He’s my son.”

It reminded me of the story Tom Hartley told the Forum for Peace and Reconciliation, set up by the Irish government in Dublin. Hilda, Tom’s mother, was seeking a visit with Tom who was being held in Musgrave RUC barracks in the early 1970s. When she told an RUC man she had a right to visit her son, he told her, “Mrs, you have no f…..n rights.”

It also reminded me of the occasions when my own mother would send me a change of clothes in a brown paper bag when I was in custody, either in Castlereagh Interrogation Centre or Crumlin Road Jail. On the bag was her carefully written name in large letters. I felt her presence when I looked at her handwriting and drew strength from it.

When Laurence was weak and close to death and his mother was alone with him in his prison cell, he said to her, “I’m sorry all of this came about for you.” She leaned across to him and whispered, “You know what you have to do and I know what I have to do.”

• SUPPORT FOR THE PRISONERS: On protest, political prisoners, experienced institutional torture and abuse at the hands of the prison system. These included prison guards, governors, doctors, senior civil servants at the Northern Ireland Office and at the very top in 10 Downing Street, Maggie Thatcher approved of and sanctioned the abuse of prisoners

And on his 70th day on hunger strike when he slipped into unconsciousness, his mother authorised medical intervention.

He woke up in the Royal Victoria Hospital to the sound of a female voice speaking his name.

He was alive. He was totally exhausted; physically, psychologically and emotionally.

In his cell in the prison hospital, he experienced the close by deaths of Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Tom McElwee, and Mickey Devine and the ending of the hunger strike by Paddy Quinn and Pat ‘Beag’ McKeown when their relatives intervened.

‘Time Shadows’ took 40 years to write. It is an ‘on the record’, minutely-observed account of a gruesome period where prisoners and prison staff battled it out over a fundamental issue – was the struggle for freedom politically motivated or was it, as the British incredulously claimed, a criminal enterprise.

The prisoners paid a heavy price but they won the moral and actual argument that they were political prisoners. The people also paid a heavy price outside the prison with over 60 people dying on the streets.

Lorney also deals frankly with the circumstances that led to the end of the first hunger strike in 1980 and which led inevitably to the second hunger strike. He makes the point that he is, ‘in general’, non-judgemental about those who left the protest but, in the book, he makes an exception in the case of the late Brendan Hughes and Richard O’Rawe. Both left the protest shortly after the end of the second hunger strike.

He criticises Brendan Hughes for unilaterally ending the first hunger strike, without the authority to do so, and criticises Richard O’Rawe for his unfounded and discredited claims that the IRA’s Army Council had rejected a deal just before Joe McDonnell died.

Of this, he says, “We held firm. And it cost us a lot. It cost us an awful lot. And yet it was ‘one of our own’ who in one short sentence sowed division, animosity and doubt.”

On a blank page facing the prologue, Lorney has this single quote from Leo Tolstoy, “Patience is waiting. Not passively waiting. That is laziness. But to keep going when the going is hard and slow – that is patience. The two most powerful warriors are patience and time.”

The prisoners were truly “warriors of patience and time” and kept going when it was “hard and slow”.

Jim Gibney is a Republican activist, former political prisoner