27 January 2022 Edition

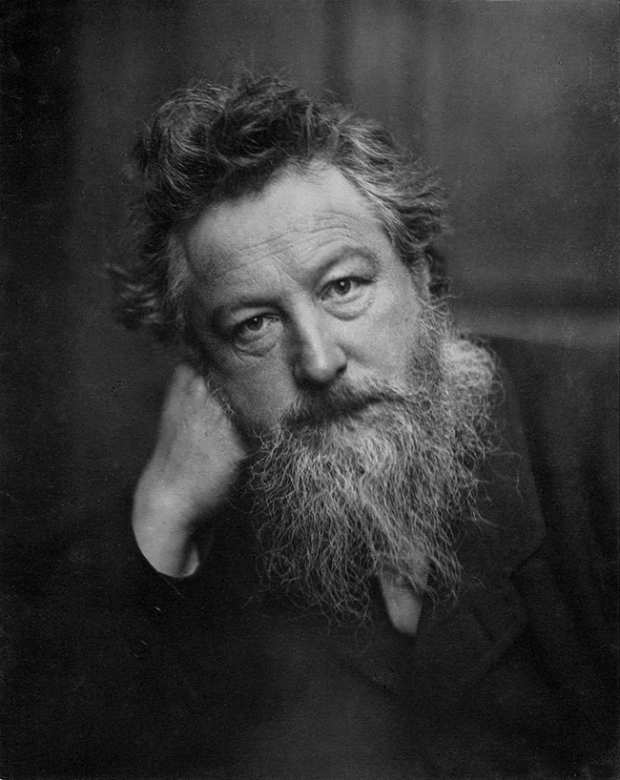

William Morris & Ireland

“The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make”

William Morris

In ‘Labouring Men’, the historian Eric Hobsbawm argues that “the really interesting and original contributions to Marxist theory in these islands came from men like William Morris and James Connolly.”

His elevation of Morris and Connolly is revealing. Admittedly, in some regards, it would be difficult to find two more divergent characters. One born and raised in a sphere of privilege and comfort; the other spent their childhood enveloped in overcrowded, urban squalor. One prophesised about a world revolution that never materialised; the other went out and made revolution, ultimately meeting his end before a firing squad.

However, on closer inspection, the parallels are clear to see. Both William Morris and James Connolly were revolutionists first and foremost. Both men adhered to an educationalist revolutionary creed, placing their faith in the working class ahead of any other strata of society. Neither trusted parliamentarian-led movements, mindful of the vitiating compromise and moderation that comes from constitutionalism.

While perhaps most widely remembered today for his imitable Arts and Crafts design work – whether wall coverings, stained glass, carpets, furniture, or tapestries – in his own time, William Morris was equally known for his social activism and political pronouncements.

Morris was converted to socialism in December 1882 following a series of lectures organised by the Democratic Federation (later renamed the Social Democratic Federation). The following month, he joined the Federation and so began 13 years of unfaltering activism, lecturing, and writing in aid of socialist revolution.

However, the SDF ultimately proved to be too stifling for the increasingly revolutionary Morris. Its founder, Henry Hyndman, treated the party as his own personal fiefdom and his controlling, domineering leadership ultimately drove away the SDF’s most capable personalities.

In December 1884, ten members of the SDF’s executive, including William Morris and Eleanor Marx, publicly denounced Hyndman and resigned from the SDF. The following month, in January 1885, this same breakaway grouping launched an alternative political vehicle: the Socialist League.

Four years later, the SL would be the first political organisation that a young James Connolly joined.

Connolly was there…

In April 1889, James Connolly - having just left the British Army - reunited with his brother John in Dundee, Scotland. It was there that he joined the SL. While the League was technically a splinter organisation, both the SL and SDF operated in Scotland as loose networks of social activists and trade unionists. Indeed, despite the opposition of both sets of leaderships, many Scottish activists even held joint-memberships.

John Connolly, James’s brother, was the secretary of the Scottish Socialist Federation, the collective title adopted by several Scottish branches of the SDF. The Scottish Socialist Federation openly took in members of the SL also and - when John left for Edinburgh - James took over as secretary.

When assessing Connolly’s later political writings, it is important to appreciate these formative political forays and ideological groundings they provided. It was through the study-groups of the Scottish Socialist Federation that Connolly was first introduced to socialist and anti-colonialist theory.

In this environment of fertile exchanges of new ideas, Connolly first honed his analytical framework. In the words of Donal Nevin:

“All of Connolly’s writings on economic and social issues are infused with the basic premises of Marxism as propagated in Britain in the last decade of the 19th century when he was imbibing his ideas from Marxist leaders of the British socialist movement in parties which were avowedly Marxist, the Socialist League and the Social Democratic Federation”.

Within such groups, the works of William Morris were to the fore. Accessible and communicable, Morris provided a straightforward articulation of socialism, unencumbered by the clunky translations or verbose style of other socialist tracts.

His writing was complimented with an artistic flourish and often incorporated imaginative, allegorical story-telling. In later years, both James Connolly and James Larkin would often quote Morris in speeches or reproduce extracts of his writings – whether from Commonweal, A Dream of John Ball, or News from Nowhere – in the newspapers they edited.

The Irish Question…

In October 1877, before his subsequent conversion to socialism, William Morris travelled to Tullamore, Co Offaly, to decorate Charleville Castle. During this visit, his aristocratic employers informed him that the area had once been “the very centre of Ribbonism” and how “even last year, a man was slain there for ‘agrarian’ reasons.” Also purporting that “an old man had told them how he had seen the [1798] rebellion; twenty miles of country burning in a straight line, the cabins and villages fired by the Orange Yeomanry.”

Not yet politicised, Morris’ reaction to such tales was that of a bystander and, in almost stereotypical English fashion, responded, “and these unreasonable Irish remember it all.”

Despite such flippancy, however, on his journey from Dublin to Charleville Castle, he did make a note of passing the Curragh, “where our army of occupation sits...”

Even before his socialist awakening, Morris knew occupation when he saw it.

Morris’ appreciation of ‘the Irish Question’ developed further as he entered the arena of political organising. In an appeal to London’s Irish community, he addressed a packed meeting of the National League, on Blackfriars Road, in May 1883. As he later recorded, “I was able to please them by assuring them of my sympathy for their views, and also by telling them I had read and admired translations of their ancient literature.” Enthusiastically adding, “one man who I spoke with afterwards knew all about the old stories and could speak Irish well.”

In April 1885, the SL’s newspaper Commonweal, which Morris edited, carried an ‘Irish Notes’ column. Written by the Irish novelist Elizabeth Casey (under her penname E. Owens Blackburne), the notes provided a detailed timeline of British misrule in Ireland from 1607 to 1798. However, the feature was ultimately a one-off initiative and Casey’s activity with the SL never progressed further.

During these early years, the SL unfortunately paid minimal attention to Irish affairs. Indeed, as late as 1885, William Morris was openly advising that, when it came to independence, the Irish people should “make up their minds that even if they have to wait for it, their revolution shall be part of the great international movement; [then] they will be rid of all foreigners that they want to be rid of.”

This suggestion that the people of Ireland shelve their freedom struggle - and instead wait on a fabled global uprising - was wholly detached from material conditions and grossly patronising.

In April 1886, Morris visited Ireland once again. This time for a series of lectures on art and socialism. This visit would prove a turning point in Morris’ attitude towards Ireland.

Addressing an audience of 600 in Dublin, the renowned public speaker made a rare faux pas; when he inadvertently referred to Dublin’s main street by its ‘official’ name, Sackville Street, rather than the popularly adopted O’Connell Street.

As he later recorded, “A great to-do followed this blunder, which, on a hint from the chairman, I corrected with all good will, and so was allowed to go on, with cheers.” The meeting continued with little further commotion, besides a spontaneous rendition of ‘God Save Ireland’ from the floor at the conclusion.

His time in Dublin decidedly convinced Morris of the necessity of Irish independence, particularly as a precondition for any meaningful advance for socialism in Ireland could take place.

His previously held position that the Irish should wait was dispelled. As he observed, “until the Irish get Home Rule, they will listen to nothing else, and equally so that as soon as they get Home Rule they must, deal at once with the land question.”

Commonweal began to cover Irish affairs more frequently and in greater detail. By July 1886, Morris was astutely predicting that the British government would ultimately look to divide Irish nationalists “into moderates and irreconcilables” and that “the more unmanageable will not be asking for a mere Dublin parliament, but will be claiming his right to do something with the country of Ireland itself, which will make it a fit dwelling-place for reasonable and happy people.”

Morris also defended Charles Stewart Parnell against the infamous forged letters, printed by The Times, purporting to show the Parliamentary leader’s support for the Phoenix Park assassinations. From the pages of Commonweal, he provocatively challenged Parnell’s accusers, writing, “Was it not at least a common opinion even in England at the time that Burke had got but what he had long been asking for?”

Although a supporter of Home Rule, Morris did not naively consider it a panacea for Ireland’s woes. Arguably pre-empting Connolly’s later warning about raising the ‘green flag’ over Dublin Castle without installing a socialist system of government, Morris outlined in May 1888:

“Home rule by all means; but not as an instrument for the exploitation of the Irish labourer by the Irish capitalist tenant; not as an instrument for the establishment of more factories, for the creation of a fresh Irish proletariat to be robbed for the benefit of national capitalists. Our Home Rule means Home Rule for the Irish people, that is to say equality for the Irish people”.

Bloody Sunday…

However, William Morris’ confidence in the politics of mass mobilisation, as the primary vehicle for revolution, was dealt a severe blow by the events of 13 November 1887. A day subsequently remembered as London’s ‘Bloody Sunday’. A tragically all too common mantle in the history of British interference in Ireland.

On 8 November 1887, a public order was issued prohibiting political meetings from assembling in Trafalgar Square. However, a demonstration - in support of the imprisoned Irish Home Rule MP William O’Brien - had already been announced to take place in just five days’ time.

The demonstration on 13 November thus became a rallying point for all defenders of free speech and assembly. Attendance swelled to 10,000 and every hue of the British left was represented. However, as demonstrators tried to enter Trafalgar Square, they were faced with 2,000 officers of the Metropolitan Police and 400 soldiers of the British Army determined to stop the meeting from taking place.

Morris witnessed first-hand the unprovoked violence meted out on demonstrators by the police and army. The severity shocked him, as he later conceded, “I confess I was astounded at the rapidity of the thing and the ease with which military organization got its victory.”

By the day’s end, 300 were arrested and 200 hospitalised. Two men would subsequently die from injuries sustained. The following week, 40,000 rallied in Hyde Park to demand the release of those still under arrest and to condemn the violence of the police and army.

That evening, a small protest attempted to again gain access to Trafalgar Square again. In the commotion, a passing law clerk, Alfred Linnell, was trampled by a police horse. He would die a fortnight later.

Linnell’s funeral became a momentous occasion for the collective British left, with 120,000 mourners marching from central London to Bow cemetery. The Irish National League’s London organiser addressed the funeral and told those assembled that Linnell “fell in the same cause in Trafalgar Square that they in Ireland had fought for in Mitchelstown”, a reference to the ‘Mitchelstown Massacre’ of 9 September 1887.

As Morris later reflected, “the meeting on Bloody Sunday was called to protest against the wrong done to an Irishman and Ireland, and every man in the bludgeoned processions was an enthusiastic Home Ruler.”

A champion for Ireland…

As C. Desmond Greaves reminds us, “Connolly always spoke with admiration of the work of British socialists for Irish independence.” In Labour in Irish History, Connolly notes how,

“In Great Britain amongst the Irish exiles [the Land League had] to depend entirely upon the championship of poor labourers and English and Scottish socialists. In fact, those latter were, for years, the principal exponents and interpreters of Land League principles to the British masses, and they performed their task unflinchingly”.

William Morris was one such champion. His eventual recognition that the Irish people would not wait – and, perhaps more importantly, nor should they wait – offers an important example for the British left.

As he wrote in May 1886, “the Irish (as I have some reason to know) will not listen to anything except the hope of independence as long as they are governed by England…”

It is still a recognition that many on the left in Britain – even in our own time – would do well to appreciate.