7 September 2020 Edition

Ireland 1920 – A nation in turmoil

The Ireland of 1920 was a country at war, in the grip of a revolutionary epoch that would define the politics of the island for much of the next century. The War of Independence was intensifying, while, electorally, Sinn Féin followed up on their stunning performance at the 1918 elections with more gains in the local elections across Ireland in January and June.

1920 also saw the creation of British Auxiliary Units within the RIC, whose rampage of destruction and murder was one more episode in the blight of the British colonial record in Ireland. On top of all this was the unleashing of sectarian violence against Catholics with pogroms against nationalist communities across what is now Northern Ireland.

To mark this centenary, An Phoblacht has singled out four distinct stories of turmoil and revolution from this literally hundreds of episodes that frame this important period in the history of republican struggle.

Jim McVeigh writes about the Belfast Pogroms that began in July 1920.

Luke Callinan remembers the killing of Sinn Féin councillor Mícheál Breathnach in October 1920.

Oisín McCann looks back at the events surrounding Bloody Sunday at Croke Park in November 1920.

We also publish a chapter from Ireland’s Hunger for Justice, which tells the stories of the 22 Republican Hunger Strikers from Thomas Ashe in 1917 to Michael Devine in 1981. Here, we have selected the chapter on Cork republican Mick Fitzgerald who died on hunger strike in October 1920.

The Belfast Pogroms

Pogrom – an organized massacre of a particular ethnic group 1920 - 22. By Jim McVeigh

The word pogrom has its origins in Russia and is most closely associated with the pogroms against the Jews of Russia in the early part of the 20th Century and later the Nazi persecution of the Jews in Germany that proceeded their attempted genocide.

However, the origins of the word, pogroms have a long and frequent history here in Ireland, as long as the conquest itself. From the Plantation of Ulster, Cromwell’s ‘To Hell or Connaught’ or to the anti-Catholic pogroms that swept across County Armagh following the Battle of the Diamond in September 1795. Following the battle, the Peep o’ Day Boys took the name of Orangemen and hence in the words of G. B Kenna, “Thus was Orangeism cradled in what we now call Pogrom”.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Belfast would become the epicentre of these anti-Catholic pogroms. In 1808, Belfast had a recorded population of just 25,000. By 1911, it had increased to 385,000, a staggering rate of growth. In 1784, the Catholics of Belfast numbered around 8% of the population. By 1911, that figure had risen to 24% and was continuing to grow.

During this period of industrialisation and economic growth, Belfast’s once radical Presbyterians became the stoutest defenders of the Union with Britain. Its capitalist class would build considerable wealth upon Britain’s vast empire of exploitation. A new Protestant working class emerged that came to rely upon the employment provided by this new capitalist class. The provision of skilled and well-paid employment in places like the shipyards was used to consolidate the loyalty of many Belfast Protestants.

Many Protestants were taught by some within this new privileged class, the Orange Order and by religious demagogues such as the Rev Henry Cooke, Roaring Hugh Hannah, and latterly by the Rev Ian Paisley, to despise their Irish Catholic neighbours as a threat to their religious liberty and economic prosperity. Sectarianism and discrimination against Catholics thus became a foundation stone of industrial Belfast.

When Home Rule emerged as a Nationalist demand in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, sectarian sentiment was whipped up, not just by northern Unionists but by England’s Conservatives. Leading Tory and Unionist Lord Randolph Churchill (father of Winston) wrote at the time; “I decided some time ago that if GOM (‘Grand Old Man’ as Gladstone was known) went for Home Rule, the Orange Card would be the one to play. Please God it may turn out the ace of trumps and not the two”.

It was the ace of trumps that Churchill intended it to be. The Home Rule Bill was defeated and in the British general election of 1886, the Tories defeated Gladstone’s government.

Inevitably, the consequences of these cynical political manoeuvres were vicious attacks upon Catholic enclaves in Belfast, the Half Bap, the Newlodge, Peters Hill, Sailor Town, Ballymacarett, Ardoyne, Clonard, the Falls. The worst of these pogroms occurred between July 1920 and the founding of the new northern state in 1922. As James Connolly had predicted, Partition unleashed a carnival of sectarian reaction across Belfast. The city’s Irish Catholic population was subjected to a veritable reign of terror by the RUC, the Specials, and loyalist mobs

By the end of 1922, an uneasy peace had temporarily descended upon Belfast. However, according to the historian Jonathan Bardon;

“The price in blood had been heavy: between July 1920 and July 1922 the death toll in the Six Counties was 557 – 303 Catholics, 172 Protestants and 82 members of the security forces. In Belfast, 236 people had been killed in the first months of 1922, more than the widespread troubles in Germany in the same period. In Belfast there had been a vicious sectarian war at a time of political turmoil, and yet the statistics speak for themselves: Catholics formed only a quarter of the city’s population but had suffered 257 civilian deaths out of 416 in a two year period. Catholic relief organisations estimated that in Belfast between 8,700 and 11,000 Catholics had been driven out of their jobs, that 23,000 Catholics had been forced out of their homes, and that about 500 Catholic businesses had been destroyed.”

Following the terror of those months, the new Unionist regime set about gerrymandering the electoral map to exclude nationalists and Catholics from holding or exercising significant political power. The Special Powers Act was enacted and was used ruthlessly to suppress opposition to the regime. Discrimination against Catholics in employment and the provision of housing was promoted by the new leaders of northern Unionism. An enduring and elaborate system of religious apartheid was created.

Looking back now what is incredible is not that the population revolted against the regime in 1969, but that it took so long!

Jim McVeigh is a Sinn Féin member and trade union activist

The Killing of Cllr. Mícheál Breathnach

By Luke Callinan

In the Spring of 1920, an initial phase of the republican campaign in Galway during the Tan War began with attacks on RIC Barracks in the north-east of the county at Castlehacket and Castlegrove under the leadership of Michael Moran, an inimitable IRA Commander from Tuam.

The more intense period of conflict, however, effectively began in September 1920 with the death of RIC Constable Edward Krumm at Galway Railway Station (now known as Ceannt Station) and was reinforced by new special powers passed in Westminster to declare public emergencies and curfews.

By Christmas of that year, 13 IRA Volunteers or Republican sympathisers in Galway City and County had been killed by British Crown forces.

One of the many brutal killings of this period was the shooting dead of Sinn Féin’s Galway Urban District Councillor Mícheál Breathnach on the night of 19th October, 1920. Breathnach was born in to a large family at Headford, Co. Galway, an area that produced many Republicans during this period and that would play a key role in the Tan War and subsequent Civil War.

His parents Michael and Brigid had a shop in the town, but later moved to Galway City where they ran a public house and shop on High Street, known today as the Old Malt House. Mícheál took over the shop from his father and married Agnes Cotter of the Cois Fharraige Gaeltacht in 1907, raising a large family at their home on High Street.

Mícheál was a known Republican and when he was asked to run as a local Sinn Féin candidate in late 1919 at the age of 39 he was more than happy to do so. He was successfully elected as a councillor for Galway’s East ward along with Sinn Féin activist and solicitor Louis O’Dea in late January 1920.

Less than nine months after being elected, at around 10pm on the night of Tuesday 19th October, five Black and Tans in civilian clothing with their faces partially covered and armed with revolvers, entered Mícheál’s premises on High Street, searched it, and threw out the five customers that were there.

• Mícheál Breathnach's family at his plaque on the Long Walk, Galway

17 year old shop assistant Martin Meenaghan was ordered to knock off the lamps while the men pointed revolvers at him and Mícheál. When Mícheál asked if his assistant could get him a glass of rum, he was told by one of the men that it would be wasted on him as he would be dead within an hour.

Four of the men then marched Breathnach out of the shop and down the street, while one remained with Meenaghan. They marched 500 metres down High Street, through the Spanish Arch, and along the now iconic Long Walk facing out on to the River Corrib and Galway Bay. The Tans fired one shot into Mícheál Breathnach’s head at point blank range, killing him instantly, and dumping his body in to the river before returning to the shop and threatening young Meenaghan not to mention a word of the night’s events. One of the Tans was wearing Breathnach’s coat when he arrived back to the shop.

• Wreath Laying ceremony: Mark Lohan, Cathal Ó Conchúir and Mairéad Farrell TD at Breathnach's grave

The following morning, as Martin King of Court House Lane, Galway City, walked to work along the river bank, he noticed something unusual in the water and, on further inspection, found it to be the body of Cllr. Mícheál Breathnach. The shocking nature of his death meant that Mícheál’s funeral was one of the largest and most poignant in Galway city from this time, comparable to the major republican funeral that took place in Galway a month earlier, following the killing in action of Volunteers Seán Mulvoy and Séamus Quirke.

Many of Mícheál Breathnach’s sons were known republicans from the 1930s onward and their public house on High Street was frequented regularly by IRA Volunteers, including Tony D’Arcy of Mícheál’s native Headford, who would die on Hunger Strike in 1940 at the hands of a Fianna Fáil Government.

His son Fursa Breathnach was a former republican internee at Tintown prison camp in the Curragh, as well as a Clann na Poblachta Councillor in Galway and ITGWU official, while his grandson of the same name is today an active Republican, Sinn Féin activist, and former Ballinasloe Town Councillor.

Luke Callinan is a Galway based Sinn Féin activist

The darkest day Bloody Sunday 1920

By Oisín McCann

November 21st 1920 was one of the darkest days of the War of Independence. Ireland was in the midst of war between the IRA and the British Forces. Despite the Easter Rising being suppressed just four years earlier, the thirst for Irish sovereignty had grown exponentially. In that time, Sinn Féin won a landslide election in 1918, claiming 73 of the 105 seats available.

The following year saw the establishment of An Chéad Dáil Éireann, which would sit in Ireland’s Mansion House, the first sitting of a revolutionary Government that would claim Ireland as a sovereign, independent State.

The growing power of an ascendant independent Ireland was demonstrated in 1920 with Sinn Féin winning majorities on 24 of the 32 county councils in that year’s local elections. David Fitzpatrick’s chapter in Nationalism and Popular Protest in Ireland tells how “republicans took control” of “72 of 127 urban authorities, and 338 of the 393 boards of guardians, rural district councils and county councils”.

As the War of Independence broke out and confrontations intensified, violence on the streets of Dublin continued to grow. By mid-1920, 500 RIC Barracks had been abandoned, with 400 of these destroyed or burned across Ireland. The Irish Republic was an accepted state of mind for much of the public across the island.

• Victims and military outside Jervis Street Hospital, Dublin after Bloody Sunday 1920

In an effort to re-assert themselves in a losing battle, British Forces stepped up aggression by raiding villages and towns with great fury up and down the countryside, indiscriminately targeting women and children.

In March 1920, Sinn Féin Mayor of Cork Tomás Mac Curtain was shot dead in his home. The inquest into his death found British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, a number of his subordinates, unnamed elements of the RIC and District Inspector Oswalt Swanzy guilty of wilful murder. On Sunday 22nd of August later that year, while leaving church, Swanzy was shot and killed in Lisburn by members of the Cork Brigade of the IRA.

The War of Independence continued to rage on and Lloyd George had dispatched extra troops, Auxiliaries, and most critically more intelligence agents to Ireland. Their objective was to conduct intelligence operations against the IRA with the aim of assassinating high-ranking members. This was done after Michael Collins’ own intelligence unit had effectively infiltrated and neutralised the Dublin Metropolitan Police’s own G-Division, through its own campaign of targeted warfare.

On the morning of November 21st 1920, Collins dispatched teams of IRA volunteers to assassinate British spies across Dublin City. In total, 14 British soldiers and suspected intelligence officers would be killed in that operation.

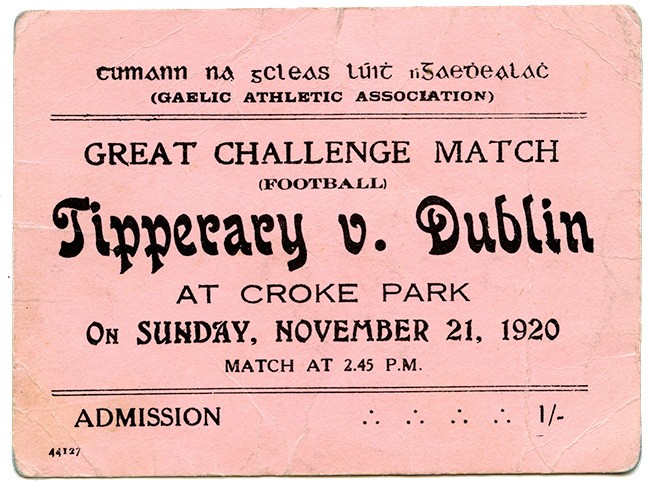

Later that afternoon, Tipperary were set to face Dublin in a challenge match in Croke Park. Tension filled the stadium as news of the morning’s successful operation spread across the grounds.

• Croke Park in the aftermath of the shootings

As crowds continued to spill into the stadium, Harry Colley, adjutant to the Dublin Brigade, Seán Russell and Tom Kilcoyne made their way through the sea of spectators. Word had reached Kilcoyne from a DMP sergeant that a force of Auxiliaries and military vehicles were being mobilised for Croke Park. The message from the IRA was clear; the game should be called off in the interest of public safety. Unfortunately, time was not on their side.

The game wasn’t long underway when British soldiers, Black and Tans and members of the RIC made their way to the ground.

11-year-old William Robinson from Dublin turned around when he heard the noise of the vehicles approaching. The first shot ripped through his chest, knocking him out of the tree where he was perched to watch the game. A second shot knocked 10-year-old Jerome O’Leary from a wall behind the goals where someone had placed him to get a better view of the match.

As gunfire tore through the stadium from centre-field, the crowd scattered, but 60 would be left injured, and 14 dead. Among those killed that day included Michael Hogan, who was playing right corner back for Tipperary.

In an effort to cover up the atrocities that occurred in Croke Park that day, British authorities tried to claim that a number of IRA gunmen were present at the match, and that the original intent of the officers on site that day was to speak to the crowd through a megaphone.

Later testimony from a Dublin Metropolitan Police officer stated clearly that the assorted British troops, Auxiliaries and RIC members began firing at the crowd as soon as they disembarked from their lorries.

The decision to target Croke Park specifically was not one made at a whim. It was a deliberate attempt to strike at the heart of Irish identity. A foreign regime attacking cultural hubs to beat the masses they are seeking to oppress is commonplace throughout history. To them, the GAA and the IRA were interlinked.

Headlines across the world rang of condemnation, further undermining Britain’s legitimacy in Ireland. Some commentators even drew comparison with the Amritsar Massacre in India, when in the previous year British Brigadier General Reginald Dyer ordered troops to fire mercilessly into a crowd of civilians, killing 379 people and wounding over a thousand more in the process.

From then on support, members and allies flowed to the IRA and the pursuit for Irish freedom from Britain grew stronger. The Dublin Brigade of the IRA scaled up its campaign of guerrilla warfare against British Forces in the city. The two sides would continue to exchange blows until the truce called in July 1921.

Today the GAA is home to over half a million members across the world, and continues to be a core part of Ireland’s cultural identity. Almost one hundred years on from Croke Park’s Bloody Sunday, and it is still seen as one of the darkest days of the War of Independence.

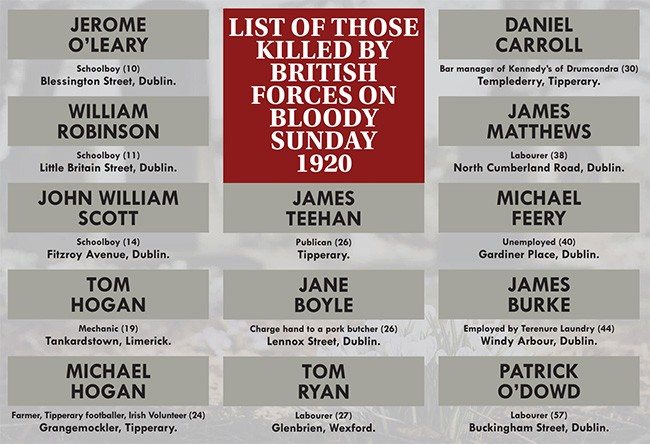

List of those killed by British Forces on Bloody Sunday 1920

Jerome O’Leary, Schoolboy (10), Blessington Street, Dublin.

William Robinson, Schoolboy (11, Little Britain Street, Dublin.

John William Scott, Schoolboy (14), Fitzroy Avenue, Dublin.

Tom Hogan, Mechanic (19), Tankardstown, Limerick.

Michael Hogan, Farmer, Tipperary footballer, Irish Volunteer (24), Grangemockler, Tipperary.

James Teehan, Publican (26), Tipperary.

Jane Boyle, Charge hand to a pork butcher (26), Lennox Street, Dublin.

Tom Ryan, Labourer (27), Glenbrien, Wexford.

Daniel Carroll, Bar manager of Kennedy’s of Drumcondra (30), Templederry, Tipperary.

James Matthews, Labourer (38), North Cumberland Road, Dublin.

Michael Feery, Unemployed (40), Gardiner Place, Dublin.

James Burke, Employed by Terenure Laundry (44), Windy Arbour, Dublin.

Patrick O’Dowd , Labourer (57), Buckingham Street, Dublin.

Oisín McCann is a Dublin based Sinn Féin activist

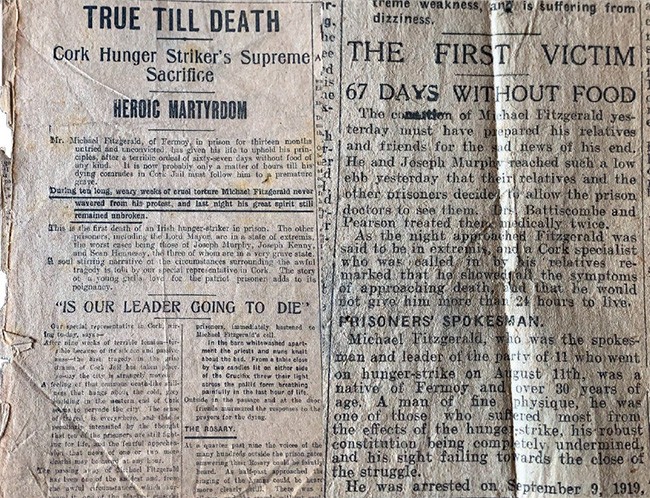

The life and death of Michael Fitzgerald

Born into the rural area of Ballyoran, roughly halfway between Castlelyons and Fermoy in County Cork, in December 1881, Michael ‘Mick’ Fitzgerald inherited an Ireland going through the upheavals of the land war.

Fermoy, the largest town in the vicinity of Ballyoran, was a garrison town with a large military presence. Many young men of the time would have sought out careers in the British Army. At one stage in the 19th Century, nearly 40 percent of members of the British army were Irish. While there was a multiplicity of reasons for joining, many simply joined due to economic necessity.

Mick was educated in the local Christian Brothers School and went on to work in a local mill. He was secretary of the local branch of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, a position which led him to develop broad sympathy with the views espoused by James Connolly and others who recognised the importance of the question of Labour in the overall national struggle.

Events in Ireland on the issue of Home Rule had reached a climax in the period between 1912 and 1914. The Anti-Home Rule Unionists had introduced the gun into Irish politics with the Larne Gunning running incident and the British Army and the Curragh mutiny had added fuel to the fire.

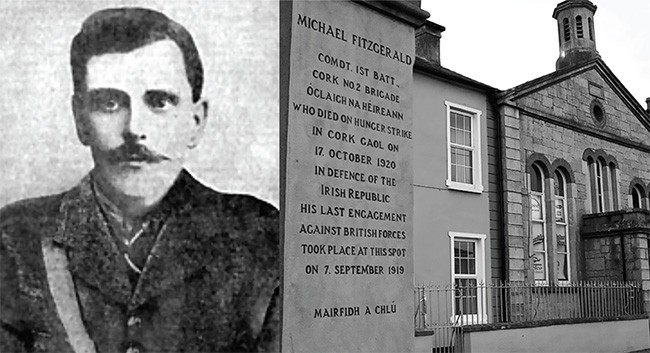

The National question was looming large and, by 1914, Mick, like many others, had realised the need for change in Ireland so he joined the Irish Volunteers. As a member of the Irish Republican Army, he played an important role in building the organisation in his local area. He soon rose to the rank of Battalion Commandant, 1st Battalion, Cork No.2 Brigade.

With the advent of the Tan War, Mick and many others found themselves thrust into the burgeoning guerrilla war which would soon engulf Ireland.

On Easter Sunday, April 20, 1919, Mick Fitzgerald led a small group of IRA volunteers in a daring raid. They captured Araglen RIC Barracks located on the border between Cork and Tipperary. Matt Flood recalled that five carbines had been secured and without a single shot being fired. Shortly after the raid, he was arrested and sentenced to three months imprisonment at Cork Gaol.

Upon his release in August 1919, he returned immediately to active IRA duty. One of the operations he participated in involved holding up a party of British Army troops at the Wesleyan Church in Fermoy. This attack was important as it was the first deliberate attack on British military during the Tan War.

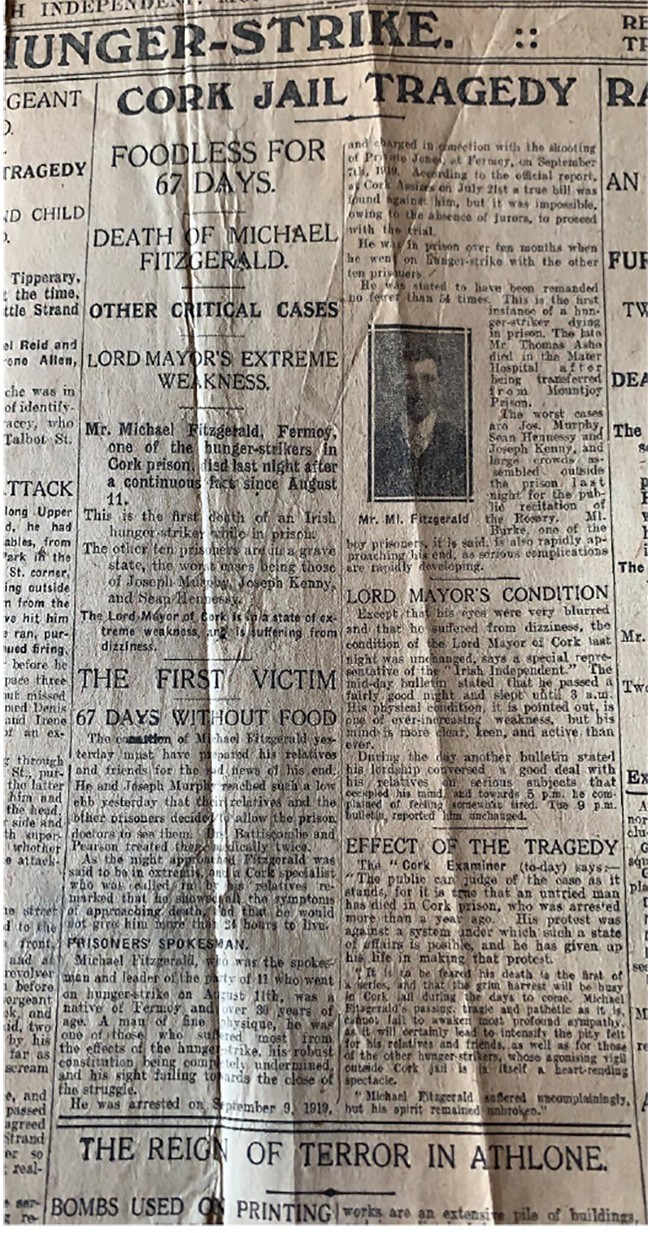

Mick was arrested along with Terence MacSwiney and nine other volunteers on August 8th, 1920. Fitzgerald’s trial at the Cork Summer assizes had to be abandoned due to the non-attendance of jurors. As part of Dáil policy, an alternative and very successful system of National and local government was introduced, which included a courts and policing system. This resulted in many refusing to co-operate with the British judicial system.

Despite the absence of a conviction, Mick was detained at Cork gaol and along with ten other prisoners, who were being held indefinitely without trial, began a hunger strike on August 11th, 1920. Limited information exists in relation to the specific journey of Fitzgerald on his long gruelling sixty seven day fast. However, the documented experiences of other Republican strikers during 1920 offer some insight into the suffering he endured:

‘Tonight, my head aches. The hardest thing of all to bear is that there are no meals hours. The Jail life hinges on the three meals, and now there is no division of the day, no beginning and no end- the head aches, the body is damp and weak, even sleep has gone……This is the darkest night yet. Death alone could find his way in here now – yes- he is there again tonight – I feel him coming towards me’.

The death of Mick Fitzgerald was the first death of a hunger striker in an Irish prison since Ashe, three years previously. When he died in Cork Jail at 9.45pm on October 17, 1920, he was aged just 38 years.

A New York times article from the following day reported: ‘STRIKER DIES IN CORK JAIL AFTER 68-DAY FAST; Michael Fitzgerald, Accused of Death of Soldier Sept. 17, 1919, Is First to Expire. ANOTHER IS NEAR THE END Prison Physicians, with Consent of the Nine Other Prisoners, Called in to Give Treatment. MacSWINEY ‘FAIRLY WELL’ Pope Asks Congregation of the Holy Office to Decide Whether His Death Would Be Suicide’

Fitzgerald’s remains were taken by his comrades to the Church of Saints Peter and Paul in Cork’s city centre. Huge crowds turned out to witness the removal and the coffin being carried in relays by Volunteers of his own Battalion.

Accounts of his church service on October 18th highlight a heavy-handed approach from the British. Attempts were made to undermine and threaten those who had come to pay their last tributes as family, friends, and Republican supporters. After the mass, British military in full uniform, including the wearing of steel helmets, invaded the church carrying fixed bayonets.

The British soldiers walked over the seats to the altar rails. An officer with a drawn revolver handed a notice to the priest warning that only a small number of people, fifty, would be allowed to take part in the rest of the funeral. A machine gun was mounted at the church gates. Despite this intimidation, which also included armoured cars and lorries carrying heavily equipped British forces shadowing the cortege, thousands of people are reported to have taken part in the funeral.

• 1920 Hunger Strikes: IRA Volunteers Maurice Crowe (Tipperary) and Michael Carolan (Belfast) recover in the Mater Hospital after the Mountjoy hunger strike had ended

His body was taken to St. Patrick’s Church, Fermoy where he lay in state overnight. On the following day, more crowds attending the funeral at Kilcrumper were threatened by the same type of intimidation as was displayed previously in Cork. A barbed wire entanglement was set up and machine guns were mounted on the bridge in the town centre. His comrades assembled again and, later that afternoon, paid a last tribute of three volleys to the first IRA volunteer to be buried at the Republican plot at Kilcrumper Cemetery in Fermoy.

General Liam Lynch had a particular friendship with and admiration for Michael Fitzgerald. When Lynch lay dying, after being shot by Free State forces in the Knockmealdown Mountains on April 10, 1923, his final request was to be buried with Michael Fitzgerald in Kilcrumper. That last wish of his was fulfilled and their graves have now become a place of National pilgrimage.

In recognition of the selfless and brave sacrifice Mick made for the cause of Irish freedom, Cork City Council named a road in Togher in his memory. At a commemoration in 2008, Pat Doherty MP spoke of ‘the duty that now falls to the present generation to continue their struggle until our ultimate aim of a free democratic 32-County Republic is achieved, the only way to pay homage to such great men to whom we owe so much’.