28 May 2020 Edition

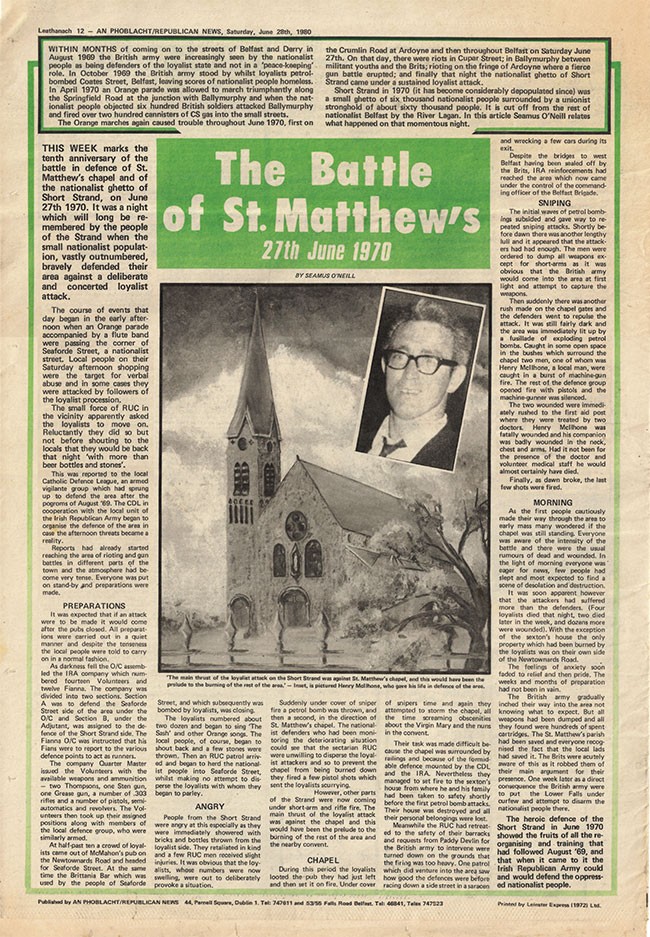

The Battle of St Matthews

When the people of Ireland and in particular the people of the Ballymacarrett-Short Strand woke up on the morning of the 28th June 1970, they woke up to a different Ireland, to a very different northern state and to a very different nationalist community in particular.

The reason for this difference happened, literally overnight, indeed in the space of a few hours, roughly from 9pm on the 27th June to 3am the following morning.

In the space of those six hours, the 50-year-old reign of the Unionist Party and its military state power, shuddered to a stand-still.

A new reality was born and a new experience began for the people of the six counties, particularly the northern nationalist people, hitherto denied their full rights as Irish citizens in their own country - trapped in a state which used its oppressive and hostile authority to impoverish them politically, economically, socially and culturally.

The first break in the chains that helped keep the nationalist people in check happened inside the heads of the people of the Short Strand and it happened on the streets of that numerically small district when the people, the IRA and the local defence force, the Citizens Defence League, (CDL), united to defend the people of the district.

In taking such a stance to arm and defend themselves, the action became ‘offensive’. At that point, the reach and influence of the unionists’ state power hit an invisible ceiling. From that night forward it never regained the omnipotence and fear it wielded over nationalists for the previous 50 years, since partition in 1920.

The IRA’s authority as the defenders of the northern nationalist and Catholic people was restored on the streets of the Short Strand as it fought alongside the CDL to protect the people against the armed and sustained attack on the district by unionist paramilitaries.

Too often this has been misrepresented as ‘inter-communal rioting’, thus masking the true nature of the attack, as in Paul Bew and Henry Patterson’s ‘Northern Ireland - a Chronology of the Troubles’.

The assault was aided and abetted by the RUC and the British Army who colluded in the attack as they ‘stood idly by’ and watched in hope, that the attack by unionist paramilitaries would raze the district to the ground. This would have forced the people to flee as they had the previous year, in August 1969, in a similar attack on Bombay Street and surrounding streets on the Falls Road and in Ardoyne in North Belfast where Catholics’ homes were also burnt down.

On that occasion the IRA were ill-equipped to repel the unionist marauders and their long-standing and justified reputation as defenders was tarnished.

In what became known as the ‘Battle of St Matthews’, the IRA emerged victorious and a new chapter began in its history as a popular national liberation army, on a par with the volunteers during the War of Independence.

All of this was of course not part of my thinking on June 27th 1970, as I went about my normal day as a 16-year-old going on 17. It was Saturday, it was warm and it was work free. A day to chill, as it would be described by a lad of a similar age these days.

I don’t recall the hours before my friend Jimmy and I went to his sister’s house in Comber Street around 7pm to babysit the children to allow her and her husband to go out for the night.

Jimmy had a few sisters with children who needed regular baby-sitters and they were generous with their appreciation and we were delighted to have a ‘free’ house a few bob and a good night’s craic.

It was in the days long before smoking was banned from public places but for some reason, I stepped from the house into Comber Street for a smoke. And that smoke and what I saw, while I was puffing away, changed the course of my life forever.

I wasn’t a complete stranger to darkened streets and men on patrol performing vigilante duty to protect their homes from attack by loyalists.

I was a vigilante myself for the previous year or so and had a ‘station’ at the corner of Bryson Street and Madrid Street beside my family home, where I and a few other young lads and men stood, keeping a weather-eye on the activities of loyalists.

The big difference on this occasion was that the men on patrol were armed. One man walked past me carrying a rifle and the amazing thing was he did so openly, not concealed.

And even more amazing for anyone to see, back then, but for a 16-year-old to witness it, the man casually strolled to the corner of the street, less than one-hundred yards from me and began to fire the rifle up Bryson Street towards the unionist Newtownards Road.

For some reason, I stood there transfixed but not afraid of what I was seeing. It was like a scene from a war movie and it was happening on the streets of my district; where I grew up and played cowboys and Indians and now there was a real gun-battle under way.

• Billy McKee, a senior member of the Belfast IRA

For the next six hours the district resonated to the sound of sustained gunfire, people screaming, an acrid smell of smoke hanging in the air; rumours of people shot, and worse to come, as more armed loyalists were heading for the district to join in the attack.

The armed man who passed me in the street was joined by a few others at their snipers’ post. From there I watched a regular exchange of gunfire with unseen loyalist snipers over the six-hour period.

Throughout the gun battle I was the only eyewitness on the street watching the defensive snipers, faces covered, protecting the people of the district. From the safety of the doorway, where I took shelter, I ‘reported in’ to Jimmy what I was seeing, while he comforted his frightened nephews.

I wasn’t really thinking about anything beyond what I was seeing. My family and Jimmy’s were literally up the street from us a few hundred yards.

They too were hemmed in but the danger of the gun battle meant that all we could do was worry about them and them us.

As dawn was breaking the six-hour ‘liberated zone’ that encapsulated the streets of the Short Strand began to fade, as the snipers melted away into the safety of people’s homes.

And with the dawn came the British Army in their heavy armour-plated vehicles circling the district, waiting their opportunity to reoccupy it. Their military might made it easier for them to retake the streets but it was over for them and the unionist regime.

Its writ, power and authority obliterated in the resistance by the people and the IRA, as a new phase in the age-old struggle for Irish freedom entered its most popular and decisive stage since partition.

I, like thousands of other republicans, settled into a life of service in what became a life-and-death struggle for decades to come.

That night the McIlhone family tragically lost their father and husband Henry. He died in the attack on St Matthew’s Church and Billy McKee, a senior member of the Belfast IRA, was seriously injured. Other families lost as well – a number of Protestants died and many were injured.

In the long struggle for Irish freedom the ‘Battle of St Matthews’ was a turning point. The people of the district endured much that night of the 27th June; they endured worse thereafter.

Their resolve and that of republicans all over Ireland ensured that the injustice of partition, unionist domination and British occupation withered in the face of the determination of a risen people.

• Jim Gibney is a Republican activist, former political prisoner and parliamentary adviser to Senator Niall Ó Donnghaile