28 May 2020 Edition

Celebrating the Connaught Rangers mutiny of 1920

When it comes to the commemorations of the events of 1916–1923, the battle continues between Fine Gael and the rest of us. As far as Fine Gael are concerned, there is nothing inspiring or revolutionary to celebrate. Nothing to see here, let’s move on.

Readers will remember the embarrassing video that the government commissioned for the 2016 anniversary of the Easter Rising, a video they hurriedly took down in the face of a huge public backlash. Unfortunately for them, there were enough of copies made that that if you are in the mood for a cringe, you can indulge with a quick search on YouTube.

Then there was the attempt to commemorate the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Dublin Metropolitan Police, with a Dublin Castle event on 17th January 2020. This, the government said, was in a spirit of reconciliation and mutual understanding. But reconciliation with who? The British government of the day was directing these forces against the Irish national movement in a policy of ‘reprisal’ that even the most wooden-headed conservative would not expect to be celebrated in Ireland today.

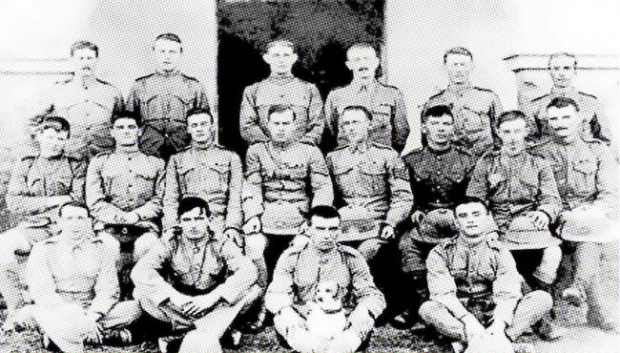

As part of this ongoing effort by Fine Gael to channel commemorations in a ‘safe’ and uninspiring direction, is their neglect of another important anniversary. It is that of a mutiny of Irish soldiers serving in the British Army in the summer of 1920. Around 350 Irishmen serving in the Connaught Rangers, stationed in India, participated in a rebellion that began on June 28th 1920. These men risked their lives to protest at the repression of Ireland and their story deserves a major celebration.

The key figure behind the mutiny was Private Joe Hawes. He later explained his action: “When I joined the British Army in 1914, they told us we were going out to fight for the liberation of small nations. But when the war was over, and I went home to Ireland, I found that, so far as one small nation was concerned – my own – these were just words.”

In particular, when Hawes had been in Clare on leave in October 1919, he’d been part of a crowd who had faced the British Army and drawn bayonets when attempting to attend a hurling match.

Soon after, stationed at Jullundur barracks near Amritsar, north-east India, where the previous year the British Army had massacred at least 400 civilian demonstrators, Hawes realised he could no longer fight in the British Army. Having talked it over with a few friends, at 8 a.m. on the morning of June 28th 1919 Joseph Hawes, Patrick Gogarty, Christopher Sweeney and Stephen Lally entrusted their belongings to an officer with instructions to tell their families the true reason for their deaths, should they be immediately executed. Then they reported to the guard room and announced they would no longer serve the British Army.

Word of this protest spread fast and groups of soldiers gathered to discuss the stand of the four men. When parade was called and Hawes’s C Company formed up, Jimmy Moran stepped out of the line to announce that he too would no longer fight for Britain. That defiant action was the trigger for a full-blown mutiny and twenty-nine more men (plus the armed duty guard) joined Hawes. Soon they were singing rebel songs and shouting ‘Up the Republic’.

Moreover, the mutiny became more serious that afternoon when their colonel arrived and ordered the troubled B Company to sit on the steps of buildings around the guard room, where he gave a speech about the regiment’s proud traditions and history, a speech that brought tears to his own eyes. Satisfied with the effect and confident of the result, he announced an amnesty for all if they would return to duty.

Much to his astonishment, Hawes, a mere private, then stepped forward into the sunlight and took over the assembly. His speech was short but effective: ‘All the honours in the Connaught flag are for England and there are none for Ireland but there is going to be one today and it will be the greatest of them all’.

B Company immediately joined in the rebellion and protected Hawes from being taken away. They released the men in the guard room; the senior officers hurried away, having now lost control of the entire barracks.

Unexpectedly in control of the situation, the 300 rebels consolidated their position and put a guard to watch the officers, also on the alcohol. They commissioned a hundred green, white and orange rosettes from the local Indian merchants and ran up a tricolour to replace the Union flag.

A major from B Company came out to urge the men to stop, on the ground that the Indian population surrounding the barracks would take advantage of the mutiny to kill them all. Once again Hawes’ gave a spirited – and internationalist – reply: “If I am to be shot, I would rather be shot by an Indian than an Englishman”.

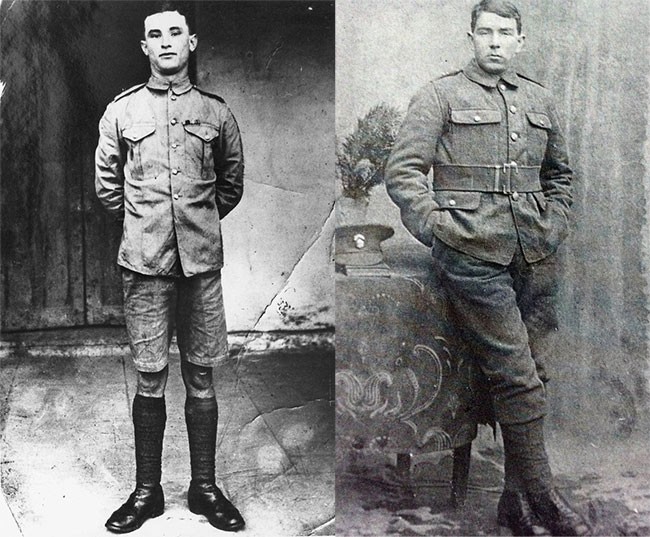

• James Joseph Daly and Joseph Hawes

In fact, the rebels had nothing to fear from Indian nationalists, who were sympathetic when the news spread of the mutiny of Irish soldiers in the British Army. One pro-Ghandi newspaper wrote that the action was an example of ‘how patriotic people can preserve their honour, defy the orders of the Government, and defeat its unjust aims.’

On June 30th 1920, the rebellion spread to other members of the regiment, who were stationed in Solon. Frank Geraghty and Patrick Kelly went to talk to the rest of C Company and in particular, to find James Joseph Daly, who was known for being a republican. Although the two rebel emissaries were arrested on their arrival, they shouted their news through the bars of their prison.

Daly rose the occasion and took the lead in bringing about forty soldiers to the Commanding Officer to announce they were taking over a bungalow in protest at repression in Ireland and would no longer serve in the British Army. Their new base was renamed ‘Liberty Hall’ and the tricolour was raised above it. Once again, rosettes were made and again too, the night air of the barracks was filled with rousing rebel songs, belted out by forty voices.

The following night, however, Daly tried to rush the magazine building on news that British troops were nearing the Solon barracks. The officers opened fire on the rebels, who carried bayonets, and two men were killed, one wounded. Desperate, Dally offered to fight any of the officers one to one with bayonets, but they just waited for dawn and reinforcements. If Daly’s plan was to fight a retreat to his comrades in Jullundur, it had failed. With the arrival of loyal troops, the Solon participants were placed under arrest.

Meanwhile at Jullundur the mutiny was ended by the arrival of the Seaforth Highlanders and the South Wales Borderers on July 1st 1920. Both these units had artillery and machine guns. The rebels had to surrender themselves into captivity, but they were determined to stick together and not let the authorities kill the ringleaders. This was as true for English rebels as Irish ones. A sergeant from Liverpool later explained at the courts martial, “These boys fought for England with me, and I was ready to fight for Ireland with them.”

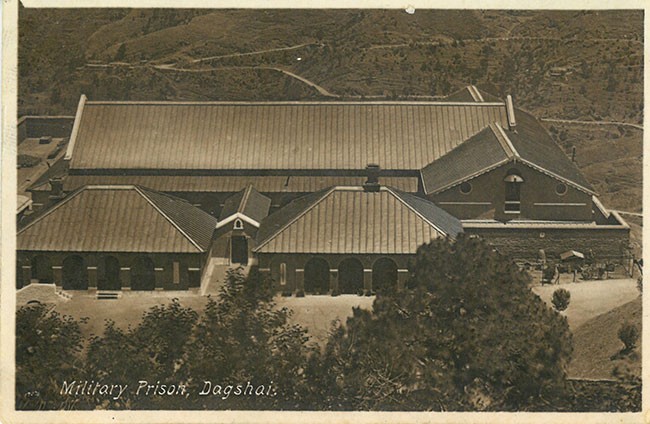

Though close to mass execution by machine gun and also to death from dehydration when penned outdoors in the blazing sun, the men resisted by physically holding on to their leaders at times, when attempts were made by the officers to drag away Hawes and nineteen others. Eventually, the more impassioned and violent officers gave way to proper procedure and eight-nine Connaught Rangers found themselves awaiting trail while in jail at Dagshai jail.

• Dagshai prison, northern India, where 88 Connaught Rangers were imprisoned after the mutiny

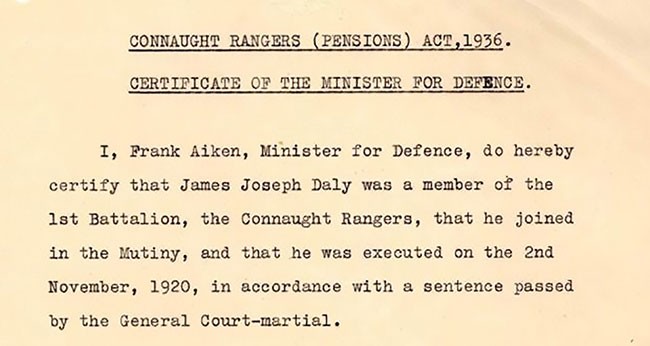

Proceedings began on August 30th 1920. Thirteen men were sentenced to death, with the other mutineers given fifteen-year prison sentences. By this time, however, the political situation in Ireland was coming to the aid of the rebels. Powerful protests, general strikes, mass boycotts and guerrilla actions had thrown British authority onto the defensive. To kill all thirteen men was likely to create a public outcry that would further harm the position of the British authorities. They commuted all the death sentences but that of Jim Daly.

As Major-General Sir George de Symons Barrow saw it, if no one were shot, that would create a very harmful precedent, not least for Indian men serving in the British Army. He needed to keep the threat of execution to prevent further mutinies.

Fortunately for the other men, they were in the public eye and so, on 9th January 1923, they were released as part of the general settlement between the Free State and the British Government.

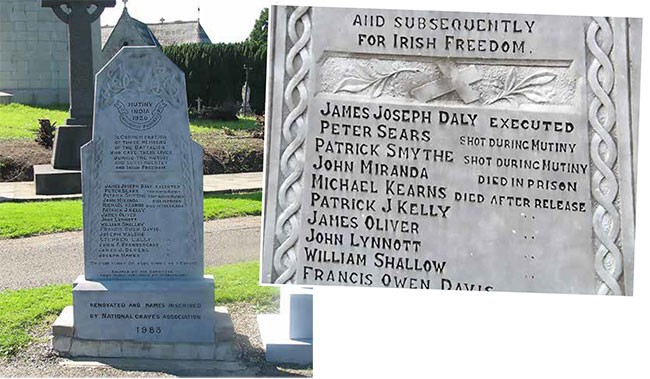

• Connaught Rangers mutiny memorial beside the Hunger Strike memorial in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin

It should be clear from this account that the men who risked their lives in 1920 in a protest against the repression of the Irish national movement deserve a heartfelt and sincere commemoration. Not least for the sake of the relatives of those involved. Instead, in an all too familiar pattern, it seems that the goal of the current plan is to belittle, rather than honour the soldiers.

At the time of writing, there is just one event planned. Reasonably enough, a new monument in Sligo will recognise three local mutineers. But the accompanying talks are in the hands of people with no sympathy for the mutiny. University of Kent historian Mario Draper’s claim to authority on this issue is his argument that the rebellion was not about support for Ireland’s national cause but local problems. His contention is that we can see the testimony of the men themselves as compromised by a desire to win a pension for their time in prison.

This slur on the reputation of the men flies in the face not only of their own evidence at the time, i.e. at the courts martial, long before any talk of pensions, but also of the British sources. These include the English soldiers who supported the mutiny, or Lieutenant-Colonel H.F.N. Jourdain’s letter to the London papers, saying that the men had been “led astray by the accounts they had received about the Black and Tans.”

Then too, there is the lie that these men were inexperienced and their real motive came from being ‘green recruits’ afraid of war. This is the position of the official regimental history.

These soldiers were veterans of the Great War, most of those on trial having been in the army for more than five years. They were not afraid of battle and their rebellion was made with the full knowledge of the power of the British Army to crush them. But they had come to realise that Britain was never going to reward Ireland for its part in the war and that enough was enough.

As Frank Geraghty put it: “I had served in France from January 1915 to the end of the war and had been wounded twice. And despite all my service, by mutinying, I knew what I was doing. But the news coming from Ireland disturbed my mind to such an extent that I was quite prepared to suffer anything, irrespective of what it might be.”

We need a proper, non-revisionist, celebration of this event and my suggestion would be a partnership between the families, Glasnevin Cemetery and those politicians who are unambiguously in favour of celebrating June 28th 1920 to hold an event (virus permitting) at the memorial to them in Dublin’s Glasnevin cemetery.

Conor Kostick is an historian and novelist.

Timeline

13 April 1919

Amritsar massacre of at least 400 civilians in North East India by the British Army, just 90km from where the Connaught Rangers would be stationed.

October 1919

Joe Hawes, Connaught Ranger, is on leave in Clare and present when troops obstruct a hurling match with bayonets drawn.

28 June 1920

Joe Hawes, Patrick Gogarty, Christopher Sweeny and Stephen Lally, C Company, Connaught Rangers, ‘ground arms’ and report to the guard room of the Wellington Barracks, Jullunder. This triggers a mutiny of around 300 soldiers who take over the barracks.

30 June 1920

Rebels send messengers to their comrades in Solon. They are arrested but spread the word and 40 men mutiny, occupying a bungalow.

Jullundur Barracks, scene of the mutiny of the Connaught Rangers in 1920

1 July 1920

Skirmish at Solon as the rebels attempt to seize the magazine. Two deaths.

At Jullunder, South Wales Borderers and Seaforth Highlanders arrive with machineguns to regain barracks.

2 July 1920

Leaders are not handed over to the authorities despite threat of mass executions.

Mid-July 1920

89 mutineers held in prison at Dagshai.

30 August 1920

Court martial of rebels.

2 November 1920

Execution of Jim Daly (aged 21).

9 January 1923

Release of the rebels as part of the Treaty agreement.

29 April 1936

Pension granted to survivors for the three years they were in prison.