28 May 2020 Edition

Brazilian democracy under attack

With Brazil challenged by a neglectful and confusing response to Coronavirus and besieged by a president who supports a return to military rule, Conor Foley explains the events that have led Brazil to this critical threshold.

On April 24th 2020, 2018 Jair Bolsonaro the President of Brazil sacked the head of the federal police force after learning that an investigation had been opened into one of his sons for inciting a demonstration calling for the military to shut down Congress and the Supreme Court.

A few days before this Bolsonaro had sacked his own health minister, Luiz Mandetta, for refusing to back calls that shops and schools must reopen in the midst of a rapidly rising death toll during the Coronavirus pandemic. Bolsonaro was also reportedly irritated with Mandetta´s criticisms that he was refusing to observe ´social distancing´ advice, going walkabout in crowded areas and hugging his supporters during repeated demonstrations demanding the return of military rule.

There are a number of ongoing investigations related to Bolsonaro´s family. One concerns another son who allegedly embezzled State funds to finance illegal construction carried out by right-wing ´militia´ groups in Rio de Janeiro. Another is one who gave the order to assassinate a left-wing Assembly member in Rio, Marielle Franco, which was allegedly carried out by two of Bolsonaro´s associates.

Bolsonaro´s Minister of Justice, Sérgio Moro, resigned from office in response to the sacking of the chief of police, alleging that the President was interfering in an ongoing criminal investigation. Brazil´s Supreme Court has also blocked Bolsonaro´s attempts to put his own nominees in both positions.

Bolsonaro is a former military officer who won the Presidency in October 2018. His notoriety comes from a series of bizarrely offensive statements during his career. He told a fellow legislator that she was too ugly for him to rape her; said that he would rather his son died than accept him as gay; repeatedly taunted black people, indigenous communities and the poor; and said that the dictatorship’s only mistake was that it did not kill enough people.

• President of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, Minister of Justice, Sérgio Moro and Luiz Mandetta sacked health minister

When casting his vote for the impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff in 2016, Bolsonaro dedicated it to the memory of the dictatorship’s chief torturer whose victims included Dilma herself. On the eve of his election Bolsonaro released a statement in which he promised to imprison his political opponents and echoed a slogan from the dictatorship era: ‘Brazil, love it or leave it’.

The scandal of Bolsonaro´s actions as President of Brazil is only matched by the manner of his election. In 2002, the same year that I arrived in the country, Brazil elected Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula) as its President. Lula was a former trade unionist and his party PT (the Workers Party) consisted of former guerrillas, such as Dilma, liberation-theology Catholic laity, environmental campaigners, feminists and the rural and urban poor. It played a key role in mobilising the protests that brought down the dictatorship, in the 1980s.

Lula´s government ran primary surpluses year-on-year, paying down its national debt and funding innovative social programmes like Bolsa Familia (family purse), while sharply raising the minimum wage. Millions were lifted out of poverty, inequality decreased slightly and education minister Fernando Haddad dramatically increased access to further and higher education.

• In 2002 Brazil elected Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula), a former trade unionist

PT rejected the neoliberal ´Washington Consensus´ and moved Brazil more firmly into the non-aligned camp, building Southern linkages with other developing countries. It did little to tackle the enormous concentrations of wealth and power in Brazilian society, though, and in mid-2005, it emerged that opposition legislators had been bribed to vote with the government, in what became known as the Mensalão scandal. This crystallised internal discontent and PT split with the loss of high-profile members, including some of the party’s original leadership.

PT had a reputation as a ‘clean hands’ party, and its achievements in office included strengthening the power and independence of the State prosecutor. Ironically, these reforms had only been achieved with the votes of parliamentarians through the Mensalão scheme.

With this strategy no longer available, PT turned to the more traditional means of horse-trading with the parties that make up Brazil’s Congress, stitching together support for its legislative programme by doling out ministries and key positions in its State-owned industries. It was an open secret that once in office some of these politicians treated it as a licence to loot.

By the time the ‘Mensalão’ scandal came to trial in 2012, the world was mired in recession. Lula was succeeded by Dilma, his former chief of staff, in 2010, and she was comfortably re-elected President in 2014. But PT lost control of the Brazilian Congress in the same year and these two crises coincided with the opening of an anti-corruption investigation, known as Operation Lava Jato (car wash). A group of judges led by Moro, devised a prosecution strategy, which was to be the biggest in Brazilian history.

By the end of 2017, over 300 people, including members of Congress and State governors, had been charged with criminal offences and over 1,000 warrants had been issued. Suspects were placed in pre-trial detention and offered plea-bargains as inducement to testify. In some cases family members were also arrested. Evidence gathered in this way was used to target more suspects and the unsubstantiated word of alleged accomplices has been deemed sufficient for conviction.

Brazil has a civil law system in which judges have an investigative as well as an adjudicative function. This means that judges sitting without juries have overall direction of a criminal investigation and then also determine the guilt or innocence of the defendant. Moro, who presided over most of these trials, also provided the Brazilian media with selective briefings or tipped them off about police raids so that these could be televised.

The effect on public opinion was electric. Huge protest marches were now regularly taking place throughout the country. A new generation of mainly middle-class Brazilians was emerging, too young to remember the dictatorship and impatient with the sclerotic inefficiency of the Brazilian State. Some linked up with the Tea Party movement in the US that was soon to become the driving force of Trump´s presidential campaign.

In October 2015, investigations revealed that the leader of the lower house of Congress, Eduardo Cunha, had stashed over US$16 million in various foreign secret bank accounts. Cunha, a strong opponent of the PT and Dilma, gave them an ultimatum; curb the investigation or he would move for her impeachment.

• Brazilain president Dilma Rousseff greeting President of Ireland Michael D Higgins in Brasilia, October 2012

The legal grounds for this were slender to non-existent, but many parliamentarians under investigation saw it as an opportunity. Get rid of Dilma, some were recorded as saying, and we can get rid of Lava Jato as well. In December 2015 Cunha accepted a petition for Dilma´s impeachment with a vote scheduled to take place in the next parliamentary session in March 2016.

A couple of weeks before this, police officers took Lula into custody in an early morning raid about which Moro had informed the press. He then leaked wire-tap conversations that Dilma and Lula had held to discuss his appointment as her chief of staff, which would have made him subject to the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, rather than Judge Moro.

Dilma was impeached in April 2016. Lula was imprisoned the following year and PT responded by deciding to use the 2018 presidential election as a fight to defend their party, government and legacy. Lula was nominated as a candidate and opinion polls soon showed him well ahead of all the other potential candidates, polling at over 40 percent. His nearest rival was the previously politically marginal Bolsonaro, polling around 15 percent. Most of the ´centrist´ candidates – who had previously dominated Brazilian politics – could not get into double figures.

In September 2018 the Brazilian Supreme Electoral Court ruled Lula ineligible to stand due to his Lava Jato conviction, which most legal observers considered to have been the result of an extremely unfair trial. PT then nominated Haddad, Lula´s previous education minister, but he had little time to build an independent profile. Nevertheless, it soon became clear that the election would be between him and Bolsonaro.

A few days before the first round of voting, Moro issued another indictment, based on a plea bargain, this time implicating both Haddad and Dilma, who had previously been untouched by corruption allegations. There seemed to be no pressing legal reason for the timing of this decision. Bolsonaro did not take part in any presidential debates during the campaign or give interviews with journalists where he would be required to answer questions. He instead relied on social media, and the support of Brazil’s powerful evangelical networks to build his base of support

On first day of polling, on 7 October 2018, it seemed for a time that Bolsonaro would win an outright first round victory. He clearly outpolled Haddad in the wealthier south and east of the country. It was the votes of the poorer north-east for Haddad that took the contest to a second round at the end of that month. Tension surrounded the second round of voting as polls pointed to a tightening of Bolsonaro´s lead, but it held up sufficiently to ensure victory. The result was greeted with a cacophony of fireworks in Brazil’s well-to-do districts. In Rio´s favelas the police celebrated by firing their automatic weapons into the air.

Within days of his electoral victory Bolsonaro made two announcements to give effect to his campaign platforms: the police, he declared, would be able to shoot criminal suspects dead on sight with total impunity and he was making Judge Moro his new Minister for Justice.

Conor Foley is a Visiting Professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro and has worked on legal reform, human rights and protection issues in over thirty conflict zones.

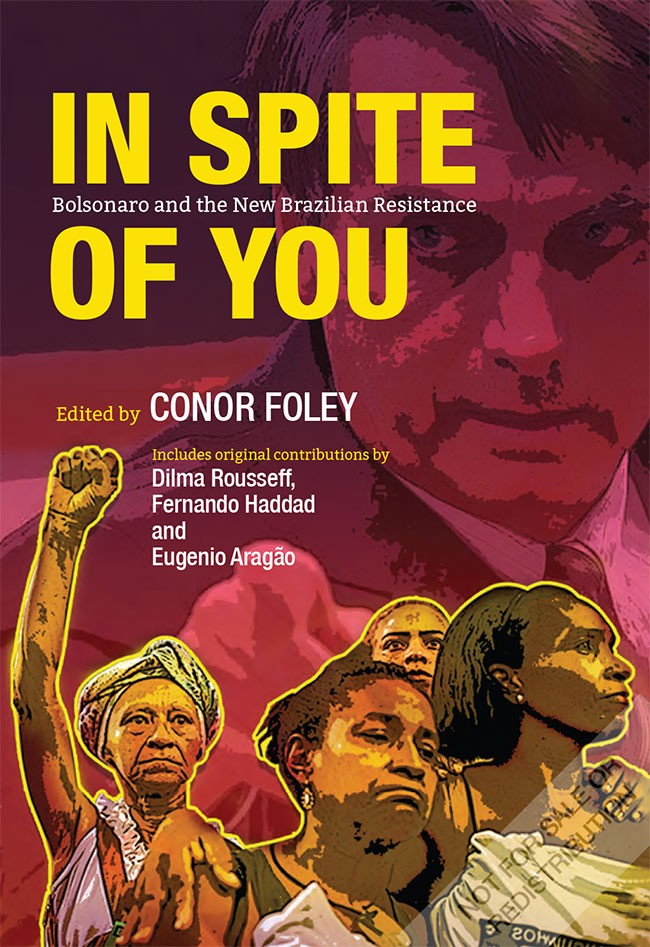

Conor Foley‘s In Spite of You, Bolsonaro and the New Brazilian Resistance, which includes Chapters by Dilma, Haddad and other leading PT activists can be ordered directly from the publisher here. https://www.orbooks.com/conor-foley/