5 December 2019 Edition

The Implications of Brexit for Border Communities

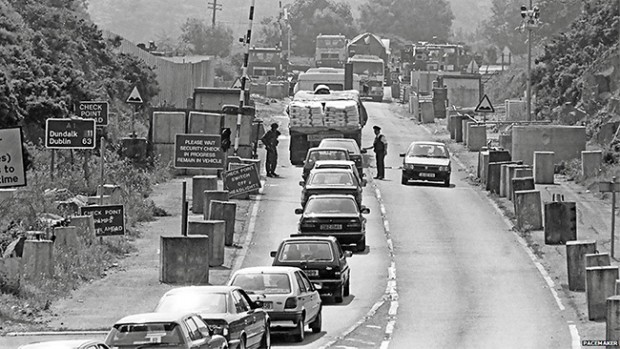

• Militarised British Army checkpoint in the 1980s

Since the first days of Partition in 1922-23, life along the artificial border in Ireland has always been precarious. Partition was intended to pacify the Unionist population who opposed Home Rule, often with the slogan that ‘Home Rule is Rome Rule’. It was important for the British Tory party to maintain a strategic base in this part of Ireland and, of course, the northern shipbuilding and linen industries brought economic benefits for the British exchequer. That was then.

In the years immediately after Partition, customs posts mostly of corrugated iron, were built at many crossings to monitor cross border traffic and impose tariffs on goods. Roads that did not have a customs post were called ‘Unapproved’. If you were caught smuggling on any of these roads you would face a severe punishment in the courts.

The nefarious activities of customs officials were part of local folklore. In the North they were known locally as ‘the water rats.’ The escapades of smugglers were also part of local folklore when I was growing up on the Fermanagh-Donegal border in the 1950’s. Local cattle-dealers, including many of my relatives, had many ‘run-ins’ with the officials, often losing cattle and finding themselves in court - if caught.

Customs posts were seen by republicans as symbolic of Britain’s continuous occupation of Ireland. In the 1950s they became targets for the IRA and some were blown up. It was common to see B-men and RUC men patrolling border roads to protect these customs sheds. They too became targets.

When Ireland and Britain joined the EEC in 1972, the Customs became redundant and the huts were locked up. Some which had been blown up were left there as reminders. However, as the long war intensified, the border became more militarised and British army checkpoints became targets for the IRA. Those British checkpoints remained until the Belfast Agreement of 1998. They were then dismantled as were many heavily fortified police stations along the border. The almost 300 blocked roads were re-opened. This all happened fairly quickly. Life returned to some kind of normality.

People living along the border enjoyed their new sense of freedom to travel without fear of hindrance or delay. Cross border trade was slowly built up and brought much needed jobs and money to local border communities. Building contractors and builders suppliers were back in business -travelling back and forth on a daily basis. The number of cross border workers increased yearly. People from Fermanagh travelled south to Monaghan and Cavan. People from Dundalk travelled north to Newry. It was all becoming so normal that we were beginning to take it for granted and had almost forgotten what it used be like. That is, until Brexit!

Since the Brexit vote in June 2016 up until the present, people in the border communities, have lived with great uncertainty about the future. Hoping that the worst might not happen, hoping that the majority vote to ‘Remain’ in the Six Counties might be respected by the British if they were seriously concerned about protecting the Good Friday Agreement. Border Communities made up of concerned local people, organised in Border Communities Against Brexit (BCAB), to highlight the anxieties of local people and to put pressure on people of influence in Europe, the USA and Dublin. People here dread a return to the ‘bad ole days’. The psychological impact on people living along the border cannot be ignored.

The Dublin government has stressed the importance of the Good Friday Agreement for the continuation of peace on the island and for the economic well-being of the whole island. Brussels too was concerned to protect the Agreement and to ensure that the whole island of Ireland continued to prosper as a member of the Customs union.

• Border Communities have lived with great uncertainty about the future since the Brexit vote

The Backstop was introduced as a guarantee in any future deal between the EU and the British to protect the Good Friday Agreement and to protect free movement and free trade on the island as an integral part of that agreement. The DUP and the right wing Tories were having none of it. Their only concern was to strengthen their relationship with the Union irrespective of the consequences for Ireland or the Good Friday Agreement. Their hard-line stance has not pleased all Unionists especially those farmers who trade in the south and those businesses which rely on cross border trade.

British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, who succeeded Theresa May, initially dismissed the Backstop. He insisted that Britain would leave the EU -deal or no deal -on October 31st. Johnson’s subsequent strategies, including negotiating a possible deal with the Irish Government and the EU, seem ultimately focussed on leading him and his party to winning a forthcoming General Election. The British Labour Party appear to be equally divided about how to take the country forward and what to do about Ireland.

• The DUP insist on leaving the EU on the same terms as the rest of the UK - though a majority in the north voted Remain

A no deal Brexit would have a huge impact on border communities but will also have a detrimental effect on the whole island. We have had twenty years of freedom and it has been a good experience. Peace in Ireland has been hard won. I had never envisaged a return to those bad old days - but I was afraid they could return as a result of the Tory government’s unwillingness to agree to a deal which included a guarantee of freedom of travel and free trade on the island of Ireland.

The DUP still insist on the Six Counties leaving the EU on the same terms as the rest of the UK –even though a majority in the north, including at least 15 per cent of unionists, voted Remain.

Once again the fortunes of the people of Ireland and especially the border communities have been considered irrelevant in London. But all is not lost! The Good Friday Agreement, an internationally binding Agreement, includes a requirement to hold a Border referendum. This must now be a priority for the Dublin government - if it is serious in preserving the integrity of the Good Friday Agreement. Border communities will be looking more and more to Dublin and demanding that the government there do the right thing and honour their commitments.

• Joe McVeigh is Assistant Priest in Enniskillen parish, Human Rights Activist and a member of Border Communities Against Brexit (BCAB)