1 May 2019 Edition

Ireland 1918 – 1922: a People’s Revolution

Remembering the 1919 Limerick Soviet

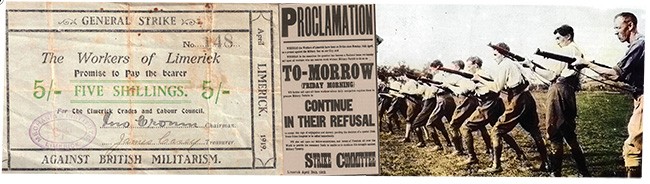

• British Army barricade at Sarsfield Bridge, Limerick, 1919

The story that is being told around the commemoration of the centenary since the War of Independence is largely focused on the actions and decisions of a small number of – predominantly male – political figures. What is typically missing from story is the contribution of a risen people and especially the Irish working class.

All across Ireland from late 1918 onwards, the empire was met with mass resistance to repression. Barracks housing the military and especially the Black and Tans were boycotted. No butter or milk came their way. Post was not delivered and it went missing. No troops could be moved by train. Attendance at the British courts collapsed: a summons meant nothing unless it was to a Dáil court. The payment of taxes to the empire broke down. And against this backdrop of crumbling authority, pressure on the British administration surged up with hundreds of strikes, including huge general strikes.

The awakening of the Irish people and the start of an avalanche of acts of popular rebellion had a very distinct moment: the successful campaign to stop conscription. Early in 1918, the British Cabinet were desperate to get more men into uniform and into the trenches. It was time to march Irishmen, young and old, out of their homes and into the fight for Empire. So on 16 April 1918, the Military Service Bill was passed.

Immediately, the leaders of Irish nationalism gathered to protest. At the Mansion House a large gathering of politicians of all parties declared their opposition to conscription. A general strike took place on 23 April 1918 and to the amazement of the participants themselves was an incredible success. All over the country, Ireland came to a complete standstill. Nothing moved. No business was open. And shocked by this display, the British administrators in Ireland retreated: not one Irish male was ever dragooned into the British army.

Wonderful success though this was, it was a missed opportunity to address the issue of partition. The leaders of the movement in the south did little to reach out to those in the north who were equally opposed to conscription. A unit of the UVF in Tyrone, for example, contacted the local IRA in the hope of a joint campaign to stop conscription. By emphasising the Catholic Church’s approval for resistance to conscription, the campaign gained respectability in the south but at the cost of leaving a potentially eager community of northern Protestants outside of the movement.

Another deep split in Unionism emerged on 25 January 1919, when the workers of Belfast entered into a bitter dispute with the employers of the city over the length of the working week. The strikers elected a Catholic leader and announced that religion would not divide them. For two weeks they ran the city, with the strike committee being called a ‘soviet’. The deployment of British troops against them saw a retreat by the workers and a sense of defeat in the aftermath of the strike.

The absence of a socialist figure like James Connolly was sorely felt at this time, especially by Belfast trade union activists like his friend Sam Kyle, who stood in the Shankill Road district in the local government elections of 1920 on a socialist and Home Rule platform. He topped the poll. Yet within a year his party was smashed and his colleagues were driven out of the workforce in the same pogroms that forced Catholics out of the shipyard. When the national movement put the breaks on socialist radicalism in the south, they isolated these potential allies in the north.

A similar sense of lost opportunity arose around the Limerick Soviet. On 13 April 1919 in Limerick, to defy the imposition of a new military pass system, the trades council called a general strike and adopted the term ‘soviet’ for their action. The strike was greeted with widespread enthusiasm and although the British authorities tried to scare the people of Limerick with the threat of an interruption to the food supply, the soviet quickly secured grain, milk and other foods to ensure the population was well fed.

Transport too came under soviet control. The soviet issued its own newspaper and perhaps most daring of all, its own currency to deal with the decline in circulating notes.

Here was a great opportunity to rally behind the people of Limerick and force a humiliating climb-down on General Griffin. The Dáil politicians decided not to call for solidarity with Limerick. The problem for the more conservative figures in the Cabinet was the fact that it was a group of trade unionists who were leading the battle and some commentators were talking about a soviet-style revolution being a possibility in Ireland. Limerick’s general strike, therefore, was contained and the British authorities rode out the crisis.

They utterly failed to cope, however, with the next outbreak of popular, radical action. As a result of the introduction of internment, a large number of men were being held in the Mountjoy Prison without trial. A hunger strike began among these men and by 10 April 1920, 91 men were refusing food.

Learning of their protest, huge crowds gathered at the jail and a general strike began on 13 April 1920. All over the country, workers stuck and declared soviets in order to control their towns. Typical was the scene at Kilmallock, East Limerick: ‘a visit to the local Town Hall - commandeered for the purpose of issuing permits – and one was struck by the absolute recognition of the soviet system – in deed if not in name. At one table sat a school teacher dispensing bread permits, at another a trade union official controlling the flour supply – at a third a railwayman controlling coal, at a fourth a creamery clerk distributing butter tickets… all working smoothly.’

With ‘unparalleled ignominy and painful humiliation’ as the London Morning Post put it, the British authorities caved in and released the hunger strikers. It was a tremendous victory and one that showed the power of the risen people.

That power was evident again within the month. In May 1920, Dublin dockers refused to unload two ships, believing them to be carrying military materials. The idea of boycotting the military spread to rail workers, who despite being threatened at gunpoint, refused to move trains that had soldiers on them. In Ireland, the belief was that concessions would have to be made, but the British Cabinet preferred to punish the whole country and the rail workers in particular, by ‘throttling’ the rail service. Train drivers were sacked for not moving their trains. It was a costly but effective protest, leading to ‘a serious set-back for military activities during the best season of the year’, as commander-in-chief General Macready put it.

By mid-1921, the only way that Britain could regain control in Ireland was to deploy 100,000 troops. That was the opinion of General Macready and it was an unpalatable one for Lloyd George: the risks, including protests in England, were too great. Although the prime minister had entered conflict with the leaders of the Dáil determined not to make any concessions, two years on he was forced to reappraise the situation.

It was not the loss of troops that swayed Cabinet thinking, around 160 British military men were killed in Ireland 1919 – 1921, a negligible figure in the minds of politicians willing to send millions to their deaths to achieve the goals of empire. Rather, it was the determination of the Irish people to oppose the establishment through boycotts, strikes, demonstrations and individual acts that obliged the Cabinet choose the path of negotiation rather than repression. Irish workers in this era were full participants and not simply passive onlookers to the struggle for independence.

• Conor Kostick is an historian and novelist living in Dublin