1 March 2019 Edition

Civil rights issues are still relevant and resonating

Derry - 5th October 1968

• ‘There are still in this society those who still want to deny rights and equality’

In 1968 Mitchel McLaughlin was on the historic Duke Street, Civil Rights march, that was attacked by the RUC. The intervening years saw Mitchel become a Sinn Féin activist, elected representative and national chairperson.

Derry - 5th October 1968

In the late sixties, outraged by the injustice and sectarianism of the Unionist Government in Stormont, a group of activists from differing political perspectives, came together to form the Civil Rights movement (NICRA). This was an early example of ‘broad-front’ politics in Ireland and was inspired by the courage and determination of the black civil rights movement in the USA, in particular by the commitment to non-violent activism.

The main issues were the allocation of public housing, a ‘one man, one vote’ electoral system, fair employment practices, the repeal of the infamous ‘Special Powers Act’ and the restructuring of the RUC.

The political context of that period was characterised by a Unionist regime which had ruled continuously since the foundation of the Six-County statelet. The Orange Order and other loyal institutions exercised considerable control over the appointment of Ministers and policies such as the Special Powers Act, gerrymandering of Local Authority districts and pernicious social and economic discrimination.

It is interesting to note that the IRA had maintained a ceasefire from 1962, despite sectarian murders and bombings by the UVF which were directed against pubs, schools and installations North and South in Ireland.

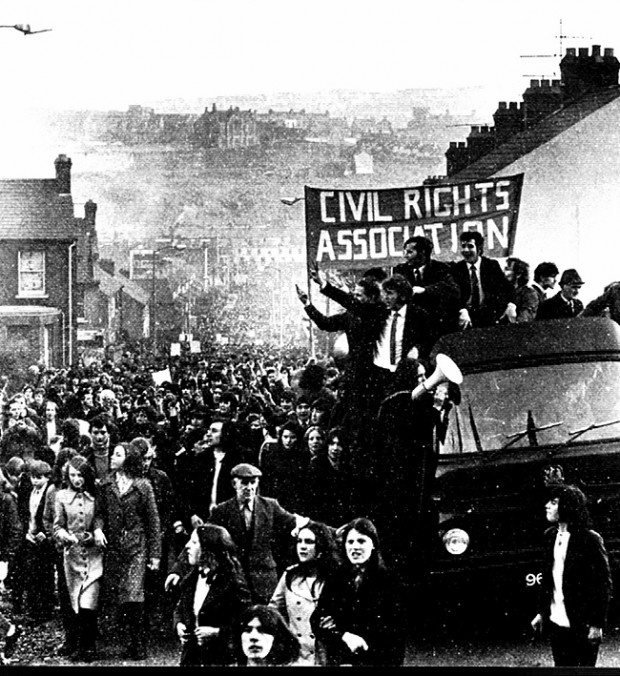

NICRA took to the streets to campaign for rights and to protest against inequality, and the first march took place in August 1968 from Coalisland to Dungannon. That march was blocked on the outskirts of Dungannon by the RUC because a small group of Ian Paisley’s ‘Ulster Protestant Volunteers’ had occupied the intended meeting point. The marchers having registered a protest that a legal march had been frustrated by the illegal actions of a much smaller group, held an impromptu meeting and dispersed peacefully.

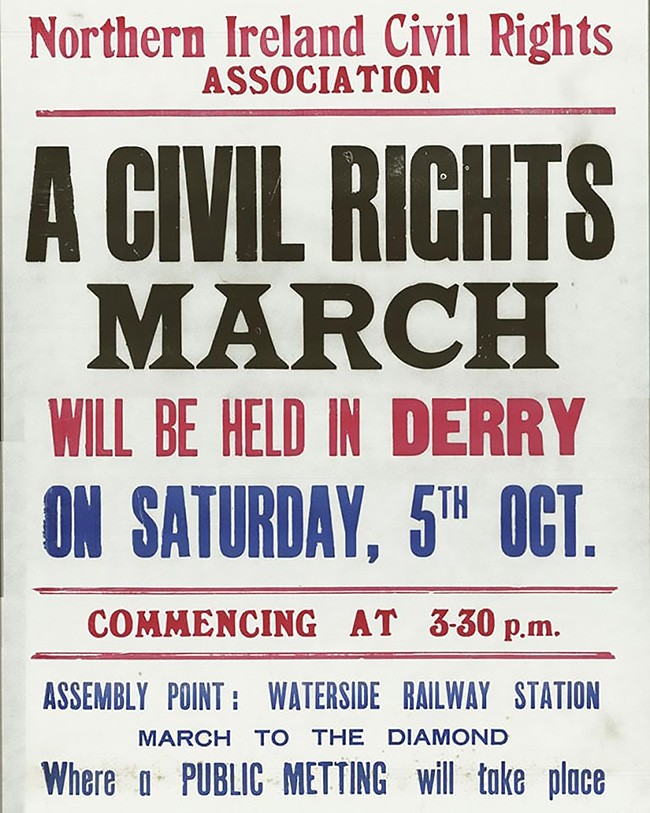

Derry 5th October was subsequently agreed by NICRA as the location of the next march. The chosen assembly point was Duke Street and the short route was intended to end with a rally in the city centre.

When the Apprentice Boys, declared that they would hold a parade on the same route, on the same day in Derry, the Stormont government announced a ban on all marches, later clarified by unionist Home Affairs Minister William Craig to exclude marches by institutions (ie Loyal institutions).

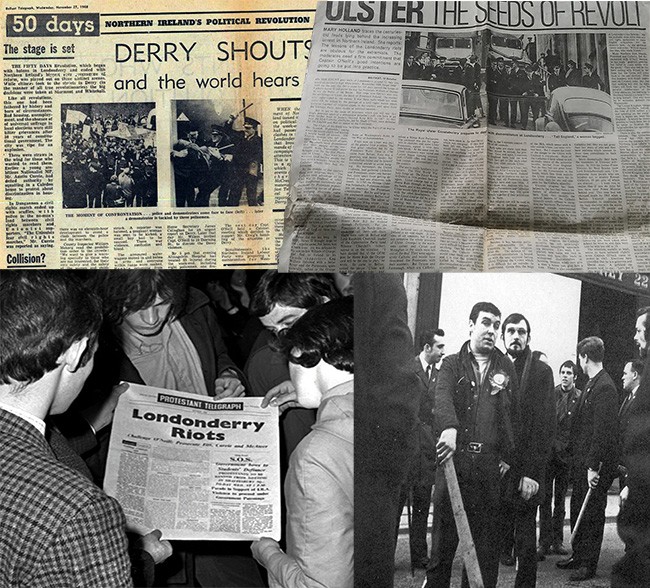

History has recorded what happened when NICRA decided to go ahead and the RUC armed with batons and water cannon, blocked and then attacked the Civil Rights march.

As a consequence, marches, sit-down protests, housing agitation etc, sprang up throughout the North, involving more and more people, routinely counter protested by loyalists who organised their own mobilisations, usually on the proposed route of the Civil Rights events.

When Terence O’Neill announced that limited reforms would be introduced to address some of NICRA’s concerns, the immediate cry from Unionism was ‘O’Neill must go’. And of course, O’Neill did go!

It can be tempting to consider these were events in our turbulent history - something to be commemorated and remembered but not really all that relevant in the here and now.

But that would be a mistake.

These issues are still very much part of who we are and where we have come from. Still relevant and still resonating.

The most blatant excesses of State violence, discrimination and sectarianism have now been outlawed, but the conditions which compelled the Civil Rights campaign are all around us.

In very tangible ways, we are still dealing with the legacy of discriminatory policies that were deployed over generations by the Unionist government and which the Civil Rights movement emerged to fight.

The deliberate discrimination against Nationalists, in employment, housing, and infrastructure, has taken generations to repair and remains an unfinished work to this day.

Furthermore, Unionism’s violent response to the just and reasonable demands of the Civil Rights campaign sparked a war which was to last for decades.

Peaceful marchers, demanding an end to the discriminatory and sectarian practices that underpinned the northern state – were ruthlessly and viciously beaten at Duke Street, Burntollet, Magilligan Strand and many other places.

In mid-August 1969, Loyalist mobs, supported and encouraged by the RUC and the sectarian B Specials unleashed a pogrom against Belfast nationalists that saw many houses on Bombay Street, Hooker Street, Kashmir Road and Cupar Street burnt to the ground.

All of the available evidence shows that the state had no intention of accommodating the democratic rights and aspirations of the wider community and that fact has confounded those who genuinely believed that a non-violent campaign could or would prevail. As far as the Stormont regime was concerned this was a unionist state for a unionist people and would remain so and they would crack as many nationalist skulls as need be to reinforce that point.

Thankfully, the Orange state is now gone and since the Good Friday Agreement, we now have the opportunity of a peaceful and democratic resolution.

The changes since 1968 are remarkable and the smashing of the Unionist monolithic Government and their dominance of policing and the judiciary are all testimony to the courage and strategic vision of those stood up to be counted. The RUC, the B-Specials and their successor, the UDR, are gone never to return.

We have made massive progress in terms of Civil Rights. This is a very different place than it was in 1968. But, my deep concern when I look back at that period in our history is that there are still in this society those who still want to deny rights and equality.

Citizens today in the north still face attacks on their electoral and civil rights, alongside the continued denial of rights to LGBTQ couples, women, Irish language speakers, and bereaved families seeking a coroner’s inquest.

Whether it is language rights, marriage equality, women’s health, or the rights of victims this discrimination is simply untenable in 2018.

Rights are also under threat by a right-wing Tory Brexit and there are unwelcome echoes of gerrymandering and the hollowing out of democracy by the recent Boundary Commission proposals.

So, there are still big challenges ahead, but as in 1968, there are those who will continue to stand up in defence of civil rights for all.

Mitchel McLaughlin is an honorary Professor in Peace Studies at Queen’s University Belfast. He was Speaker of the Northern Assembly, an MLA for Foyle and then South Antrim and Sinn Féin’s National Chairperson.