1 March 2019 Edition

The Caledon squat that triggered the Civil Rights movement

An Phoblacht interviews Civil Rights Veteran Francie Molloy

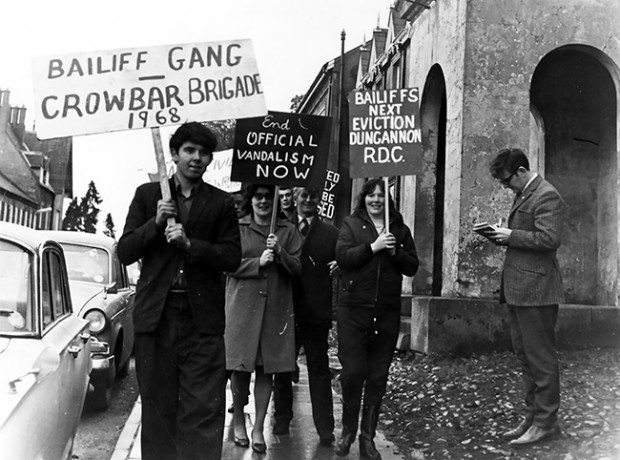

• Picket: Outside Caledon Courthouse during the trial of the ‘Caledon Squatters’ in 1968 – Francie Molloy, Mary Teresa Goodfellow, Joe Campbell and Geraldine Gildernew

Fifty years ago, republicans came together in the Tyrone village of Caledon, to make a stand against the unionist-dominated Dungannon council. Their aim was to abolish the discriminatory housing polices against Catholics practiced by the council.

An informal agreement had been reached between local priest Fr Michael McGirr and unionist politician William Scott that 15 houses built by the council would be allocated to an equal number of Protestant and Catholic families. However, the council decided that just one of these houses would be allocated to a Catholic family, while the other 14 homes would be allocated to Protestant families.

Naturally this sparked outrage in the area and Catholic families decided to take action. At this point, they had no idea that their actions would lead to the start of the now famous civil rights movement.

Fran and Mary Goodfellow, with their children, made the brave decision to squat in an empty house in the Kinnard Park area of the village. They had no other choice. The policies of Dungannon council meant that they, along with other Catholic families, had nowhere else to go.

Over the weeks and months that followed, the families were met with outpourings of support and respect for their actions. After eight months in the house they were charged with squatting, but the judge allowed them to stay in the house for up to six months. This decision was in the hope that the council would come to their senses and allocate homes on the basis of need rather than religion.

Six months later in June 1968, the RUC barged through the door of the house that the Goodfellows had been occupying. The Goodfellows, along with Mary’s mother Anne and sister-in-law Geraldine – whose daughter, Michelle, is now MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone – were dragged from the house with their children, in front of crowds of supporters and the gathered media.

• EVICTION: After the eviction from Kinnard Park in 1968

In the immediate aftermath of this, it emerged that the house next door had been allocated to a 19-year-old single girl named Emily Beattie.

This led Mary’s brother, Patsy Gildernew, to squat in the house in protest alongside two others, Austin Currie MP and local farmer Joe Campbell. After a matter of hours they were ejected from the house and subsequently charged with breaking and entering the house and squatting. Republicans including a 17-year-old Francie Molloy organised a picket outside Caledon Courthouse on the day of the case, against the charging of the squatters.

Franice Molloy, currently the Sinn Féin MP for Mid-Ulster, said that there was quite a resistance from local unionists to the picket.

Reflecting back on the events 50 years ago Mr Molloy said: “The interesting thing about the picket was that all of the people who were there and were visible were all members of ‘Republican Clubs’. In relation to Caledon and in the run up to it, there was an ongoing debate as to whether republicans were actually involved in the civil rights movement. At that stage, ‘Republican Clubs’ came about because Sinn Féin had been banned and the name was changed to accommodate that.

“I was involved in a particular Republican Club and it was the Gildernew family who were organising the picket in Caledon outside the courthouse.”

The Mid-Ulster MP described how the republican movement had found it difficult to get people out onto the streets due to previous failed campaigns.

He said: “One of the interesting things at the time was trying to find a way of mobilising the nationalist community. The 1956 border campaign had failed and in the aftermath of that there was a view republicans were at a low ebb. The mass movement of people was discussed at meetings a few years before Caledon, back in 1966.

“But housing was a big issue, and people were keen to get out and make their voices heard. The key factors of the housing crisis were that; if you didn’t have a house then you were more likely to emigrate, if you couldn’t get a job you would be likely to emigrate and if you didn’t have a home - then you didn’t get a vote. This meant that we didn’t have a chance to make a change in anything politically – so those 3 factors were very much how unionists maintained their majority.”

• Franice Molloy, Sinn Féin MP for Mid-Ulster

After Caledon, republicans sat down with people such as the Austin Currie and others who had been involved to see what could be the next stage.

“There was no evident indication that Caledon would be the trigger to the Civil Rights campaign, but after Caledon the proposal was made that we would do a Civil Rights march from Coalisland to Dungannon.

“This march was organised mainly because it was going from one principal town to another. Dungannon council had denied the homes to Catholics in Caledon, and Coalisland was a big nationalist area where there were a lot of people on housing waiting lists. We knew that there was a good possibility that we would get a big response to our campaign here.

“My role on that day in August was as a steward and when we got to the hospital roundabout, the RUC had cordoned off Thomas Street. The stewards had formed a line across Thomas Street prior to the RUC cordon, in a bid to stop any confrontation with them.”

This march was attended by around 1,000 people, and among them were the Derry Action Housing Committee. They were determined to make Derry the location of the next march and that happened on 5th October 1968. And from here, the Civil Rights cause became a national and international issue.