1 March 2019 Edition

Time for an equal and just Ireland

It is now almost a century since Britain partitioned Ireland. From the outset, violent repression of dissent and widespread discrimination defined the six counties that Unionists called Northern Ireland. But, in the 1960s, small groups of courageous people, inspired by the civil rights movement in the United States, started to campaign for equality in public housing and employment and for an end to gerrymandering in local government. They asked for nothing other than basic rights enjoyed by people in England, Scotland, and Wales. The Unionist Stormont regime responded with violence, battering them off the streets.

There, in the crack of RUC batons on the streets of Derry, the great lie was exposed – Unionists professed an attachment to Britain, but they could not countenance the rights accorded to everybody in Britain being extended to Nationalists in their Orange state.

Out of conflict

The events set in train by the repression of the civil rights movement are well known. The British Government backed the Unionists. And in doing so it precipitated over a quarter century of conflict that only started to end in 1994, when the Irish Republican Army called a ceasefire.

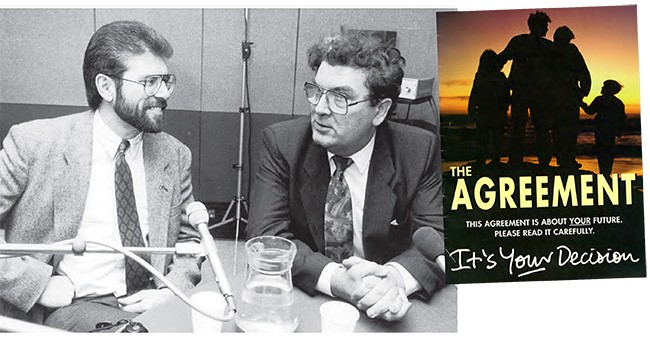

That transformative ceasefire did not come out of thin air. It was the result of work, over many years, by Gerry Adams and others in the Sinn Féin leadership. The dialogue between Gerry Adams and John Hume was critical in the development of a peaceful progress to Irish reunification. But powerful figures in London and Dublin resisted this push for peace.

However, among those who believed that we had the capacity to break the deadlock were our friends in North America. They included leaders in business and finance, the labour movement and politics. A vital element were the Irish Americans who lobbied their public representatives and engaged their attention. In doing so, they brought pressure to bear on the British and Irish governments to establish an inclusive talks process that, in 1998, resulted in the Good Friday Agreement.

The Peace Process has delivered. The RUC is gone. The British Army is off our streets. Slowly, the economies of North and South, severed and still stunted by partition, are being re-integrated. We have had over two decades of peace. The Republican cause remains the same and with Sinn Féin stronger than at any time since 1921, the great prize – the reunification of Ireland – is now within reach.

• The dialogue between Gerry Adams and John Hume was critical in the development of a peaceful progress which resulted in the Good Friday Agreement

Change is at hand

Ireland has changed since partition. The last census taken in the North, in 2011, showed that 64 per cent of those aged over 90 were Protestant and 25 per cent were Catholic; 9 per cent had no declared religion. There, among the very old, is the demographic of the North around the time of partition. Conversely, the same census returned 31 per cent of children born in the North in 2008-11 as Protestant compared to 44 per cent Catholic; 23 per cent had no declared religion.

Reflecting on these data in the Unionist Belfast Telegraph, well-known economist David McWilliams observed that ‘in one (admittedly long) lifetime, the Catholic population in the youngest cohort has nearly doubled, while the Protestant cohort has more than halved.’ For McWilliams, the numbers meant one thing: ‘we seem to be en route to a united Ireland.’

Of course religious profession does not translate to a political position. Still, election results confirm Unionism to be losing its majority. In Spring 2017, elections for the 90-seat Assembly returned only 40 Unionists – nationalists took 39 seats (27 Sinn Féin; 12 SDLP); the Alliance Party, Greens and People before Profit had 11 seats between them. The total number of votes cast for the Democratic Unionist Party (225,413), the largest pro-Union party, was only 1,168 votes greater than the number secured by Sinn Féin (224,245).

Measured by nothing other than its proponents’ intention – the creation of ‘a Protestant state for a Protestant people’ – partition is a manifest failure.

And there are other measures of its failure. McWilliams focused on the economy. When the border was first drawn, he noted, over 80 per cent of Ireland’s industrial output came from the area around Belfast. Now, the South’s industrial output is ten times greater than that of the North – exports from the South are €89bn per annum (£77.85bn), fifteen times greater than the €6bn (£5.25bn) exported from the Six Counties.

One recent study, in 2015, by Kurt Huebner of the University of British Columbia, calculated that, within eight years, a reunified Irish economy would be some €35 billion larger than two separate economies, North and South.

Of course, the disaster that is partition was never simply economic. Lives lost, rights denied, grief, and despair are not best measured in numbers.

The price of partition has been too high. A United Ireland has always been the best framework for peace and prosperity.

• ‘Irish reunification is not about bolting the North onto the South. Rather, it is about creating an Ireland greater than the sum of all its parts – one defined by equality and inclusion’ – Mary Lou McDonald

Unity in our time

In voting for the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, the people of Ireland, North and South, affirmed that they alone would determine their future constitutional arrangements.

In June 2016, a majority in the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union; the majority of people in the North voted to remain in it. The British Government of Theresa May, dependent for its survival on Democratic Unionist Party MPs, insisted that the North too must leave with England, Scotland, and Wales. It repudiated the core principle of the Good Friday Agreement – that there would be no change in the constitutional status of the North without a simple majority of people, North and South, approving it. And in refusing to countenance some form of special status for the North, the British Government displayed arrogant indifference to the consequences for employment and education, social services, and, above all, peace in Ireland.

The Brexit Crisis has laid bare the injustice of partition: as long as it suits the short-term interests of London, a minority – a minority in Ireland and, in this instance, a minority even in the North – can prevail over a majority.

But the writing is on the wall. In summer 2018 former Democratic Unionist Party leader Peter Robinson, speaking in Glenties, County Donegal, argued that Unionists should prepare for a United Ireland. He would accept, he said, the results of a border poll in favour of reunification: ‘As soon as that decision is taken every democrat will have to accept such a decision.’ And he predicted that the wider Unionist community would accept it, and look to the protections that the Good Friday Agreement guarantees to all.

Given the collapse of Unionists’ majority in the North, the challenge for their current leaders is simple – Unionists must involve themselves with others, not least Republicans, in imagining the shape and form that Irish reunification takes.

In 2018 Deirdre Hargey became the sixth Sinn Féin councillor to serve as Mayor of Belfast – tellingly, all six Republican mayors have served since 2002. Speaking at her installation, party president Mary Lou McDonald reiterated the Republican position – Irish reunification is not about bolting the North onto the South. Rather, it is about creating an Ireland greater than the sum of all its parts – one defined by equality and inclusion, where sectarian division and segregation have no place, where all cultures are accorded respect, and where all our children enjoy the peace and prosperity necessary for achieving their full potential.

Rita O’Hare is Sinn Féin’s representative in the United States.