1 March 2019 Edition

The importance of Soloheadbeg 1919

‘Flashpoints, ‘most contentious’, must be ‘handled with care’ – these are just some of the establishment media warnings about the next phase of Ireland’s centenary commemorations. Specifically these health warnings above deal with the Soloheadbeg ambush launched by the IRA in January 1919. Aengus Ó Snodaigh gives an informed background to the Soloheadbeg attack, dispelling much of the revisionist commentary emerging about the War of Independence.

On the very day that Ireland was asserting its right to govern itself in the Mansion House, Dublin, 100 years ago, an IRA attack, though unconnected, was to have as profound an effect on the course of Irish history.

The events of that day in Soloheadbeg, near Limerick Junction, County Tipperary, were not the first IRA attack on crown forces since 1916 or even the first to result in crown force casualties. Since 1916 a secret war was being waged throughout Ireland.

A reading of the pamphlet ‘Two years of English Atrocities in Ireland 1917-18’ confirms this. Listing killings by the RIC; the baton and bayonet charges against public meetings by British soldiers and police, and the ‘official’ number of civilian casualties; raids and seizures; suppression of newspapers; and the introduction of repressive legislation in the period, the pamphlet also gives a invaluable list of the hundreds arrested, charged and imprisoned for “political offences”. Sometimes it lists the ‘crime’ for which they were convicted, including giving their name in Irish, singing seditious songs, travelling without a permit or smuggling weapons and explosives.

During these years seven people were shot or bayoneted to death by soldiers or the police, six including Thomas Ashe died in prison or owing to broken health shortly after release from jail. I have found only one crown forces’ casualty in the period, that of a District Inspector Mills who died from blows of a hurley when he led a charge against an anti-conscription march in Dublin on 14 June 1918.

It becomes obvious that during the two years prior to 1919 both the IRA and the state were gearing up to a major conflict. The IRA was recruiting, training and arming its Volunteers. Sinn Féin and the other organisations engaged in challenging English rule in Ireland were upping the ante through their electioneering, the anti-conscription campaign, the blatant defiance to English rule, using the Irish language, singing national songs, breaking curfews, organising public meetings and dances to promote republicanism and to exert the right to free speech and assembly.

South Tipperary was no different from anywhere else in Ireland. During 1917 and 1918 Volunteers were openly drilling and parading in uniform and when in March 1918 two prominent Volunteers were charged with illegal drilling 200 Volunteers were mobilised to descend on the courthouse in Tipperary. “The district inspector sent for military reinforcements, who were surrounded, before the Volunteers entered the court and made a laughing stock of the proceedings.”

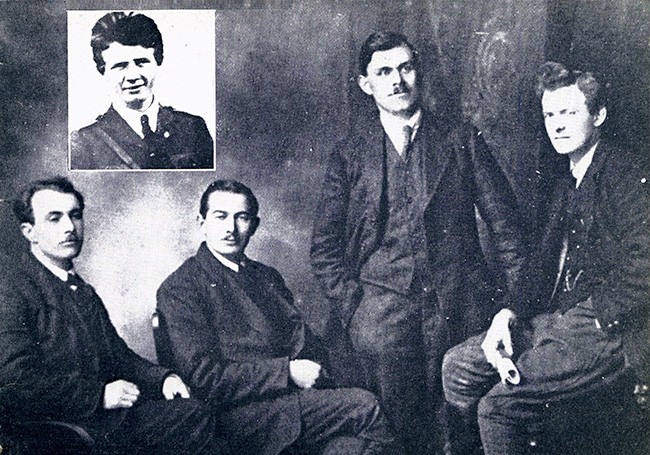

• Séamus Robinson, Seán Treacy, Dan Breen, Michael Brennan and Seán Hogan (inset)

When information filtered through to the Brigade prior to December 1918 of explosives being transported in their area they began their preparations. Lar Breen, a brother of Dan, was sent to work in a local quarry to gather intelligence. He confirmed that a delivery was expected around 16 January but the exact date and route couldn’t be confirmed. The Volunteers had to lie in wait for a few days before word came that the convoy was on its way.

Those involved on the day of the operation were four officers of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade IRA; Seán Treacy, Dan Breen, Seán Hogan (then only 17) and Séamus Robinson. They were joined by five other Volunteers: Tadhg Crowe, Mick McCormack, Paddy O’Dwyer (Hollyford), Michael Ryan (Donohill) and Seán O’Meara (Tipperary) - the latter two being cycle scouts.

Robinson, who participated in the 1916 Rising, was the organiser and Treacy, a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood since 1911, was the logistics expert.

In their planning for the ambush Treacy and the others were unsure of the size of the police contingent which would be guarding the gelignite and made preparations for various contingencies, including a guard of up to 12 RIC men. Tadhg Crowe was to guard the policemen when they were captured while Paddy Dwyer was the lookout who was to follow the convoy from Tipperary town.

On the eventful day Dwyer saw the explosives, 160 pounds of gelignite, being loaded on a cart and heading off with a guard of two policemen. He cycled ahead and watched as they took the long route to the Soloheadbeg quarry. He took the short route and informed the anxious Volunteers of the convoy’s size and movements. The horse was being led by two workmen Edward Godfrey and Patrick Flynn, while the two policemen, Constables Patrick MacDonnell and James O’Connell, walked behind with their rifles slung over their shoulders. As they passed Cranitch’s Field near the quarry the policemen were called on to surrender by masked men. When they took up firing positions Seán Treacy, followed by Breen and Robinson, opened fire.

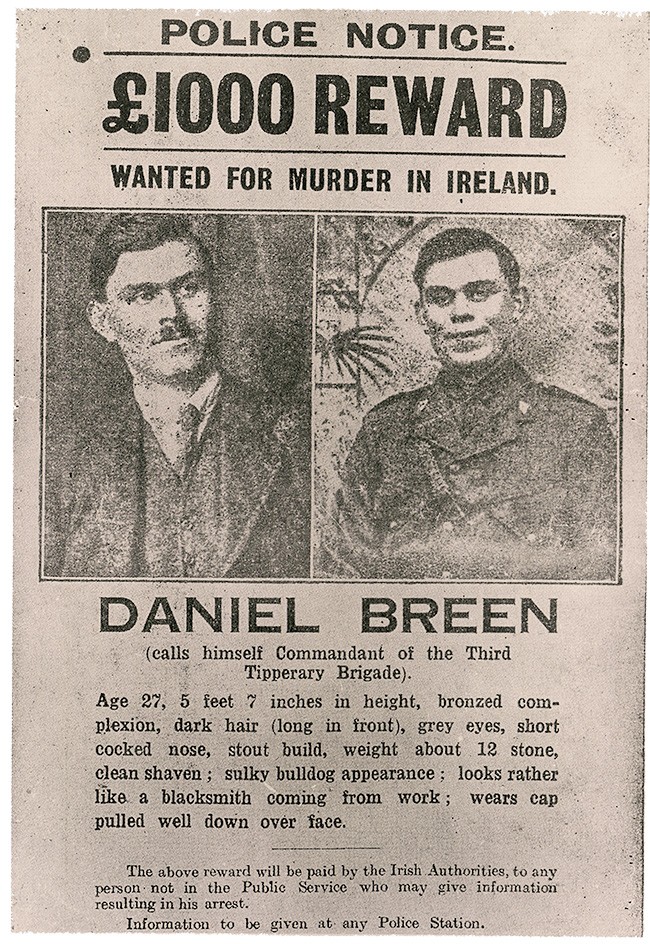

• 'Wanted Poster' issued for Dan Breen

Leaving the two RIC men dead on the road the IRA hurried the horse and cart out of the area, burying the sticks of gelignite in a hide close by. Two sticks were dropped at other locations to throw the crown forces off the scent.

The Volunteers went on the run. GHQ were anxious that those involved would go to the USA until the situation calmed down, but the Volunteers refused. Sean Treacy said “any fool can shoot a peeler and run away to America’’. Instead, he asked that a proclamation directing all British troops to leave Ireland be issued. Condemnation for the killings was swift and from every quarter, including local republicans. Breen states:

“The people had voted for a Republic; now they seemed to abandon us who tried to bring that Republic nearer, for we had taken them at their word. Our former friends shunned us. They preferred the drawing-room as a battleground.”

Dáil Éireann said nothing, though some Sinn Féin leaders publicly disapproved of going down the path of armed insurrection once more. It wasn’t until April 1921 that Dáil Éireann, at Erskine Childers’ bidding, formally declared hostilities against Britain.

Tipperary was declared a ‘special military area’ and all fairs and markets were banned. Military reinforcements were rushed to the area and a major hunt was on for the IRA men. A reward of £1,000 initially offered was increased to £10,000, but to no avail. The men involved remained on the run and they all saw regular action in the subsequent war, some making the supreme sacrifice for Ireland’s freedom.

As with other ambushes of the time the sole purpose of the ambush in Soloheadbeg was the capture of explosives. An order curtailing military style operations from the IRA GHQ meant no major operation occurred for a few months after Soloheadbeg. The official newspaper of the Volunteers, An tÓglach took a different line stating ten days after Soloheadbeg that Volunteers could use “all legitimate methods of warfare against the soldiers and policemen of the English usurper, and to slay them if necessary to overcome their resistance”.

The ambush at Soloheadbeg, County Tipperary, took place on 21 January 1919.

Aengus Ó Snodaigh is a Sinn Féin TD for Dublin South Central.