30 April 2018 Edition

The Conscription Crisis of 1918

mass Irish resistance to the British Government

We are not going to be driven to that slaughter-pen in Flanders at the bidding of a government that is dripping red with the blood of our best countrymen. – Hanna Sheehy Skeffington

Between the 1916 Rising and the December 1918 General Election the biggest crisis faced by the British government in Ireland and the most seismic shift in Irish politics was the confrontation provoked by the attempt to impose conscription – compulsory service in the British Army by men of military age in Ireland.

By the spring of 1918 the war was well into its fifth horrendous year and there was no stopping the mass slaughter that since shortly after its beginning had seen millions of men transported to the fronts to be annihilated in industrial scale warfare. With Russia out of the war after the new Soviet Republic made peace, Germany was able to launch an all-out offensive on the Western Front in March which threatened to break the Allied line completely.

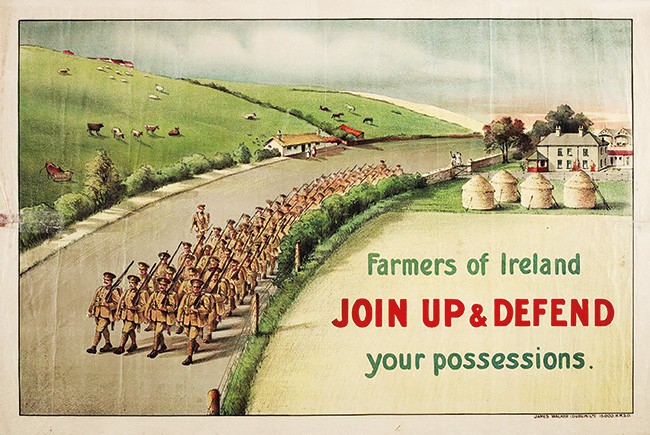

Britain was running out of cannon fodder and the War Coalition made up of Prime Minister Lloyd George’s Liberals and the Conservative and Unionist Party set their sights on the young men of Ireland. Recruitment to the British Army from Ireland, while very substantial, had failed to meet War Office expectations and it had declined as the war went on. This was due to a combination of horror at the scale of casualties, nationalist disillusionment with British broken promises of Home Rule, inspiration by the bravery of the men and women of the 1916 Rising, and revulsion at the executions, mass imprisonment and repression which followed the Rising.

Even before the Rising there had been concern in Ireland that conscription might be imposed. The President of the Irish Volunteers, Eoin Mac Néill, was not aware of the plans of the Irish Republican Brotherhood for a Rising and was against offensive action. However he did support armed action if the British government tried to impose conscription. A letter in the ‘Irish Volunteer – Óglach na hÉireann’ in October 1915 from the Anti-Conscription Committee called on Nationalist Ireland to organise at once against conscription. The Volunteer Executive issued directions to every Irish Volunteer that in the final resort it is his duty to “lose his life rather than suffer himself to be disarmed”.

In December 1915 a public meeting against conscription filled Dublin’s Mansion House to overflowing and was addressed by Eoin Mac Néill and PH Pearse who said that “if any man loved the English Empire, let him go and fight for the Empire, but that the men of Ireland would never submit to be conscripted”.

In January 1916 when conscription was introduced for Britain, but not Ireland, John Redmond in the House of Commons said that he was not opposed on principle but he did not think it was necessary and would be counter-productive in Ireland “under the conditions of the moment”. Eoin Mac Néill condemned Redmond for this statement while crediting Redmond’s deputy John Dillon with speaking strongly against conscription in the Commons. “Mr Redmond will learn one of these days that his attitude has ceased to command any respect among the Irish people,” stated Mac Néill prophetically.

John Redmond died in March 1918; his hopes of a Home Rule Ireland, dominated by his Irish Party and within the British Empire, had been shattered by the war and the Rising. The death-blow to his party was struck by the British Cabinet when on 28 March it decided to impose conscription in Ireland. Top British general Sir Henry Wilson said he was “not afraid to take 100,000 – 150,000 recalcitrant conscripted Irishmen into an army of two and a half million fighting in five theatres of war”. US President Woodrow Wilson, conscious of the strong Irish lobby in the United States, warned of trouble there if conscription were imposed on Ireland.

On 8 April Dublin City Council passed a resolution that warned the British Government “against the disastrous results of any attempt to enforce conscription... any such insane proposal, which, if put into operation, would be resisted violently in every town and village in the country, ending in a great loss of life and establishing a battle front in Ireland…” The motion called on the Lord Mayor Laurence O’Neill to invite Irish Party, Sinn Féin and Irish Trades Union Congress leaders to meet him to organise a national campaign against conscription.

On 10 April Lloyd George introduced the Military Service Bill to increase the military age in Britain to 51 and to impose conscription in Ireland. In a typical publicity gesture, the Prime Minister accompanied the announcement of conscription with a promise that the Government would prepare to enact Home Rule legislation. After many such broken promises this ‘sweetener’ was regarded with deep cynicism in Ireland.

Some in the British administration in Ireland also warned Lloyd George’s government against conscription. Joseph Byrne, Inspector General of the Royal Irish Constabulary, predicted chaos if it were attempted while Bryan Mahon, head of the British Army in Ireland, said the Government “might as well conscript Germans”. But these voices were ignored while Field Marshal Lord French and the Imperial establishment in London urged Lloyd George to go ahead.

The Military Service Bill was passed in the House of Commons on 16 April by 301 votes to 103. The Irish nationalists all voted against and John Dillon, who succeeded Redmond as leader of the Irish Party, led them out of the House and back to Ireland in protest. This was effectively the end of the substantial Irish nationalist presence in the British House of Commons which had existed since the time of Parnell. The initiative now passed to Sinn Féin, pledged, since its Ard Fheis in October 1917, to an Irish Republic, to abstention from Westminster and to establishing a National Assembly in Ireland.

Lord Mayor Laurence O’Neill convened the anti-conscription conference in the Mansion House on 18 April. Sinn Féin was represented by its new President since October 1917, Éamon de Valera, MP for Clare, and by its founder Arthur Griffith. For the Irish Party there were MPs John Dillon and Joe Devlin. The trade union movement had William O’Brien, Thomas Johnson and Michael Egan. William O’Brien MP represented the All for Ireland League; Tim Healy MP represented independent interests.

This was a very broad front, including individuals and parties that had been vehemently opposed to one another. The presence of such a strong trade union delegation was highly significant and was to prove decisive in the subsequent campaign.

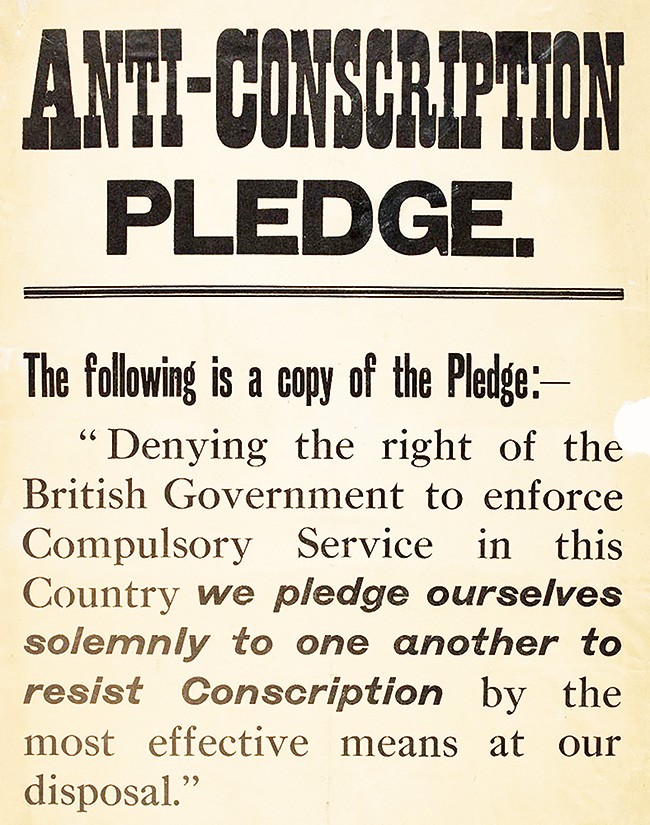

The Mansion House meeting adopted the anti-conscription pledge:

“Denying the right of the British government to enforce compulsory service in this country, we pledge ourselves solemnly to one another to resist conscription by the most effective means at our disposal.”

The meeting also issued a joint declaration which took its stand on “Ireland’s separate and distinct nationhood” and denied the right of the British government to impose conscription and said that the passing of the legislation in Westminster “must be regarded as a declaration of war on the Irish nation… The attempt to enforce it will be an unwarrantable aggression…”

De Valera made clear that, whatever the others did, the Irish Volunteers would resist in arms any attempt to enforce conscription. He had also conveyed this to representatives of the Irish Catholic bishops. Their normally cautious and conservative stance was challenged by conscription and they had little option but to support the determined opposition to it.

The Mansion House conference adjourned to send a deputation consisting of the Lord Mayor, Éamon de Valera, John Dillon, Tim Healy and William O’Brien (trade union leader) to Maynooth where the bishops were meeting. The deputation urged the bishops to support the pledge, which they did, and they issued their own statement:

“An attempt is being made to enforce conscription upon Ireland against the will of the Irish nation and in defiance of the protests of its leaders… We consider that conscription forced in this way upon Ireland is an oppressive and inhuman law, which the Irish people have a right to resist with all means consonant with the law of God.”

When the delegates returned to Dublin that evening thousands of people were gathered outside the Mansion House to cheer them.

The Irish Party had withdrawn its candidate from the Offaly by-election on the next day, 19 April, thus ensuring that Sinn Féin candidate Patrick McCartan was returned unopposed.

On 20 April, the Irish Trade Union Congress held an emergency conference in the Mansion House attended by 1,500 delegates. It was decided to have a general strike on 23 April. The Irish Women Workers Union marched to City Hall and pledged to join the resistance.

On Sunday 21 April, hundreds of thousands of people throughout the 32 Counties signed the anti-conscription pledge. Preparations then began for the general strike.

The Irish trade union movement had grown enormously since the 1913 Dublin Lockout. The largest union, the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, had 5,000 members in 1916. By the end of 1918 the ITGWU had 68,000 members. It was the backbone of the strike on 23 April.

Historian of the ITGWU, C Desmond Greaves, has described the strike as “the greatest shut-down in Irish history”. Factories, shops, schools and workplaces of all kinds closed. Workers paraded in towns throughout the country and the strike was effective in every county. It was incomplete in Belfast and surrounding districts yet 3,000 workers, many of them Protestants, attended an anti-conscription rally outside City Hall. In Ballycastle, County Antrim, it was reported that Orange and Green marched together with bands playing ‘The Boyne Water’ and ‘A Nation Once Again’.

The British Labour Party and Trade Union Congress issued a joint statement with the Irish TUC condemning conscription.

9 June was ‘Lá na mBan’ when thousands of women gathered all over the country and declared:

“Because the enforcement of conscription on any people without their consent is tyranny, we are resolved to resist the conscription of Irishmen. We will not fill the places of men deprived of their work through refusing enforced military service.”

It was a measure of the depth of hostility to Ireland in the British government that, despite this mass opposition, they still proposed to go ahead with conscription. In May Lord French was appointed Lord Lieutenant-General and General Governor of Ireland, after he had told Lloyd George he would only accept the post if he could be a “military Viceroy at the Head of a quasi-military Government”. He said of potential conscripted men: “If they do not come, we will fetch them.”

Most of the Sinn Féin leadership was arrested on the basis of the concocted ‘German Plot’ in May. The next month martial law was proclaimed across much of the country. Sinn Féin won the East Cavan by-election with Arthur Griffith on 21 June but the British response was to ban Sinn Féin, the Irish Volunteers, Conradh na Gaeilge and Cumann na mBan in July.

British repression continued but the mass resistance of the Irish people forced them to postpone the ‘Order in Council’ that would have implemented conscription and it was never introduced before the First World War ended in November 1918.

The attempt to impose conscription mobilised people as never before in support of Irish independence. But it also exposed the extent to which the British government was prepared to coerce the Irish people to remain within the British Empire despite their repeatedly expressed democratic will.