27 November 2017 Edition

The Manchester Martyrs – 150th anniversary

Remembering the Past

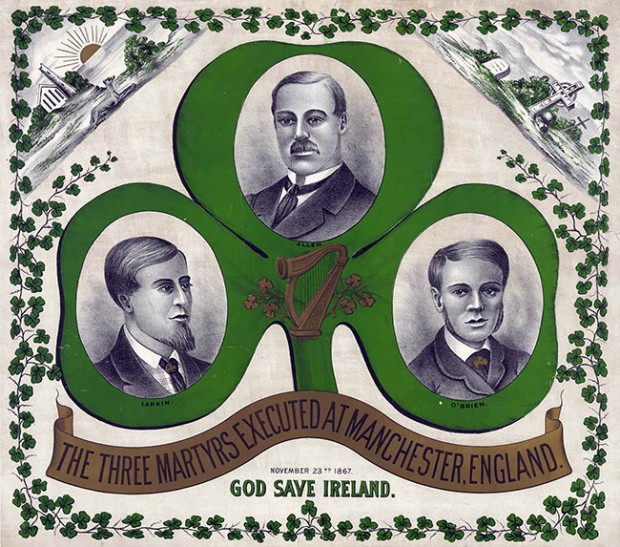

150 YEARS AGO this month, the trial, conviction and execution of three young Irishmen in Manchester caused a sensation throughout Ireland and Britain. The political reverberations were to continue for decades. The three men were William Philip Allen, Michael Larkin and Michael O’Brien – the Manchester Martyrs.

The framing and show-trial of these men, their dignity in the face of death and their defiance of British rule in Ireland re-inspired the Fenian movement, helped to push Charles Stuart Parnell into politics and pushed future British Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone into prioritising ‘The Irish Question’.

On 18 September 1867, Fenian leaders Colonel Thomas Kelly and Captain Timothy Deasy were being transported in a horse-drawn prison van through Manchester. A large group of Fenians attacked the van and succeeded in rescuing the two men.

During the rescue, police Sergeant Charles Brett who was inside the van, was accidentally killed when Dublin Fenian Peter Rice fired a shot through the keyhole just as Brett was looking through it.

There was a general outcry against the Irish in England. In Manchester, scores of Irish people were rounded up, many being assaulted in custody.

Five Irishmen were charged with the murder of Brett and were put on trial by a Special Commission of two judges at the end of October. Along with Allen, Larkin and O’Brien, the others charged were Edward O’Meaghar Condon, an Irish-American Fenian and an Irish Royal Marine Thomas Maguire, who had no connection with Fenianism.

The trial was conducted amid the highest security, with British military guarding the prisoners in transit and in the court, making it clear that this was a show-trial and these were to be regarded as highly dangerous men.

All five were found guilty of the murder of Brett and sentenced to death.

Michael Larkin told the court:

“I am dying a patriot for my country and Larkin will be remembered in time to come by the sons and daughters of Erin.”

Edward O’Meaghar Condon told the judges:

“You will soon send us before our God and I am perfectly prepared to go. I have nothing to regret, to retract or take back. I can only say: God Save Ireland!”

The cry “God save Ireland” was taken up by the other prisoners in the dock and it inspired a popular ballad that for many years was regarded as the national anthem and is still sung to this day.

Allen said in a written statement before his execution:

“It is well-known what my poor country has to suffer and how her sons are exiles the world over; then tell me where is the Irishman who could look unmoved and see his countrymen taken prisoner and treated like murderers and robbers in British dungeons?

“May the Lord have mercy on our souls and deliver Ireland from her sufferings. God save Ireland.”

Thirty-five journalists who had attended the trial wrote a petition to the British Government, calling for a reprieve for Thomas Maguire. They challenged the tainted evidence on which he was convicted. Thomas Maguire was reprieved – yet it was the same evidence that convicted the other four.

O’Meaghar Condon was also reprieved because he was a United States citizen and the British Government commuted his death sentence for purely political reasons.

That left Allen, Larkin and O’Brien for whom there was to be no reprieve.

On the night of 22 November, the three men in their cells in Salford Prison awaited execution the following morning. Outside, a mob of thousands gathered. Fuelled by drink and anti-Irish hysteria stirred up by the British press and politicians, they chanted and howled for vengeance. In stark contrast, the next morning Allen, Larkin and O’Brien walked with dignity to their deaths by hanging on the scaffold outside the walls of the jail.

It was one of the last public executions in Britain. It was also one of the worst.

The executioner, William Calcraft, botched the hangings. Allen died instantly but, unknown to the crowd, after the three fell out of sight through the trap door, O’Brien and Larkin were not dead. Calcraft ‘finished off’ Larkin and was about to do the same to O’Brien when the priest, Fr Gadd, stopped him. O’Brien died in the priest’s arms.

There were mass demonstrations in honour of the Manchester Martyrs in Ireland, the USA and wherever the Irish were exiles. Many monuments to their memory were erected in the following decades.

They also inspired poets. Perhaps the best tribute was written by a Fenian journalist and poet, John Francis O’Donnell, who actually witnessed the executions. Part of it reads:

There are three graves in England newly dug

In England there are three men less today –

Allen, O’Brien and Larkin – their brief sun has set,

To rise in God’s clear day.

I saw them, the unconquerable three,

Mount the black gallows for their country’s faith,

As with high heroic scorn for life they kissed

The frozen lips of death.

The thin, pale face of Allen, O’Brien’s gaze

And Larkin, fainting from the press of doom,

Seemed like the Trinity of Ireland’s trust

In that foul morning gloom.

’Twas over and they fell; one little pause

And the sun, battling with the mist, broke out,

And with a glory to November new,

He hemmed them round about.

The worst was done that vengeance could achieve

Or centuries of hatred fashion forth;

And England glared down from the scaffold rail –

The Hangman of the Earth!