27 November 2017 Edition

The bitter fruits of the British Empire

BOOK REVIEW

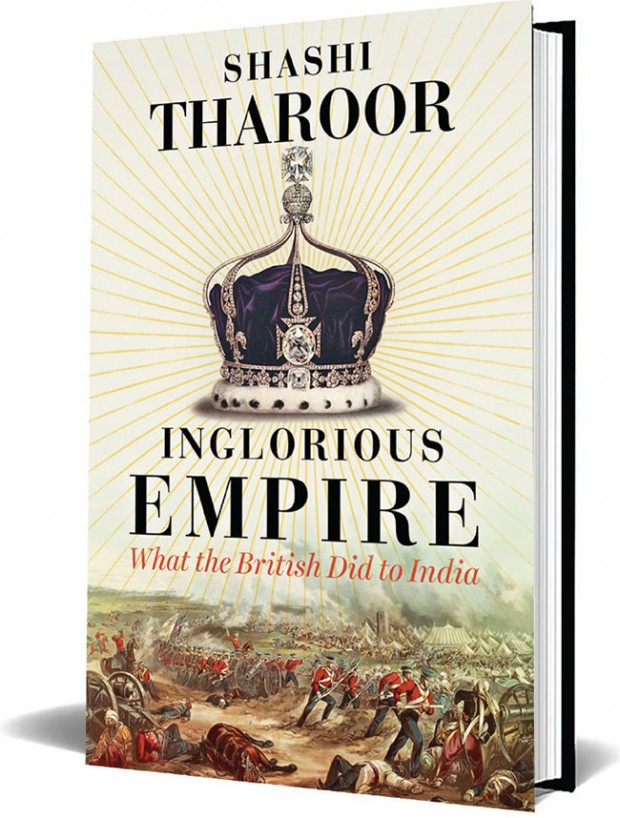

Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India. Shashi Tharoor. Hurst & Company €18

EVEN IF this book about Britain’s Indian empire is by an author named by the World Economic Forum in Davos in 1998 as a “Global Leader of Tomorrow” (scary), his study of how the British Empire damaged India is a damning indictment of imperial rule and its economic imperatives.

Fifty years before the British East India Company began its conquest of India, the country’s share of the world economy was 23%, as large as all of Europe put together; by the time the British left in 1947, it had dropped to just over 3%. Statistics can lie but this one points to an unvarnished truth.

Inglorious Empire explains how this happened, beginning with the emblematic case of the destruction of India’s textile manufacturing by the imposition of tariffs and the flooding of the Indian market with cheap cotton imports from Britain, a part of what Tharoor calls the East India Company’s “schlock and awe” policy.

Underlying the conquest and maintenance of the empire were assumptions of racial and cultural superiority (an enduring after-effect of such attitudes played a role in the Brexit vote) which fuelled the illusionary notion that it was for the betterment of those being ruled.

Brute force was used when necessary – India’s Bloody Sunday occurred in 1919 at Amritsar when at least 379 peaceful protesters were shot dead – but the passivity of the governed allowed the British in India to never exceed 0.05% of the population.

The arguments that would justify Britain’s role in India’s history are rationally exposed as defending the indefensible.

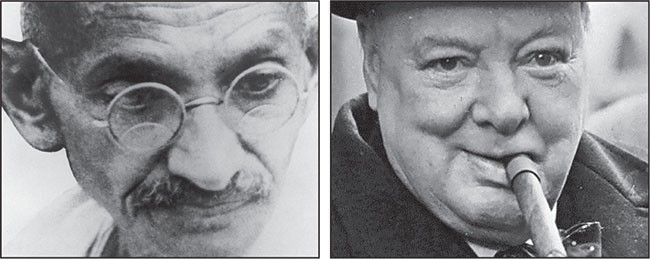

The rule of law, of incontestable value, was introduced but its application was distorted by racial bias and it served as an instrument of colonial control. The crime of “sedition” (used against nationalists like Gandhi) the outlawing of homosexuality and the criminalising of adultery for married women – but not men! – have been retained by the modern Indian state and used in its courts.

Britain, alarmed by Hindu and Muslim soldiers rebelling in unison in 1857, adopted a policy of divide and rule. Tharoor recognises the origins of such a policy “evidenced in the only already-white country the British colonised, Ireland”.

• Gandhi was charged with sedition; British hero Churchill blamed famine on ‘Indians breeding like rabbits’

The formation of the Muslim League was instigated by the British as a response to the growing influence of the nationalist and secular Indian National Congress party and it was declared a Hindu-dominated organisation. Pitting Muslims against Hindus was, of course, to have disastrous consequences – eventually leading to partition and the creation of Pakistan – and it discredits the idea that the political unity of India was a British achievement.

Another aspect of Irish history reverberates in Britain’s policy towards India: famine.

No large-scale famine has taken place in India since independence but some 30million Indians needlessly died of starvation during the Raj. Market forces were sacrosanct and unbudgeted money was not to be imprudently allocated to relief measures, echoing the ‘reasoning’ that allowed a million Irish to perish during An Gorta Mór. Just as grain continued to be exported during Ireland’s famine, foodgrains from India were exported to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) during the 1943 Bengal famine. Churchill blamed that catastrophe on Indians for “breeding like rabbits” and when the scale of the tragedy was brought to his attention he peevishly asked: “Why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?”

Shashi Tharoor does not deny the benefits that accrued to Britain’s jewel in the imperial crown: law and order was important, newspapers were introduced and, at the risk of seeming frivolous, he singles out cricket, tea and the English language. But the myth that bringing railways to India was a noble achievement is effectively deconstructed, as is the argument of Empire apologist Niall Ferguson that Britain in India served as a benign avatar of globalisation.

Inglorious Empire is a book worth reading and remembering. It is not a hand-held view of history but one that pans back to present its case in a carefully-reasoned and lucidly written manner.

In the long run, India has flourished but, as the author concludes, human beings do not live in the long run; “they live, and suffer, in the here and now” and India has suffered terribly from British colonial rule.