2 October 2017 Edition

Americana

Irish music is being colonised by American music – ROBERT ALLEN wants to know why no one has noticed

• Donal Lunny and Christy Moore played with Moving Hearts

“NOW take Leo Hallissey for example,” sings Luka Bloom for the infamous Letterfrack sessions of the early ‘noughties’, “he’s a bogman.” To background laughter, he strums his guitar. “He’s a bogman,” rhyming, the audience beginning to sing along. “I’m a bogman. Deep down it’s where I come from.”

You know what, he’s right. We all come from the bog and no matter where we travel it is where we come from. Have we forgotten this again? Ten years before those sessions, we had forgotten. The term was derogatory.

We had even forgotten why we wrote ballads and songs and made music, and now we no longer make songs for fun or make songs that matter.

“Why is there no one like Christy [Moore] anymore?” asks a man from Ballycastle, taking the time to lament the sounds of the ’70s and ’80s when Planxty wanted everyone to follow them up to Carlow – “rooster of a fighting stock, would you let a Saxon cock crow out upon an Irish rock, fly up and teach him manners”. And Moving Hearts wondered whether this was the end of our pride and glory – “if you stand up for what you believe in be prepared to be shot down, oh what will you do about me?”

Around the time Leo Hallissey was organising his bog weeks and sea weeks around the sound of the sessions (and thinking about putting out a few CDs), guitar man Steve Earle arrived in the West. He fell in love and promptly wrote about his experience, recording a track with box player Sharon Shannon for her Diamond Mountain Sessions.

Earle explained:

“Two or three years back (in the late ’90s) I took a little sabbatical in Galway to work on my book and not write songs.”

He never managed it. Galway Girl was one of four songs he wrote.

“A year later I was back surrounded by women who play like angels and the results speak for themselves.”

Not the first

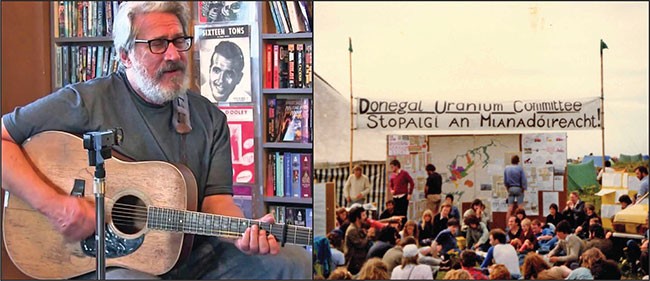

The man who wrote The Revolution Starts Now was not the first American songwriter to seek the muse on our western shores. Seattle singer-songwriter Jim Page arrived around the time of the anti-nuclear demonstrations at Carnsore in the late 1970s and promptly wrote Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Russian Roulette and was forever grateful for Moving Hearts’ rendition:

“This is the power of the future and the future marches on / and they call in all their favours / all their political gains / while the spills fill the rivers and settle in the plains.”

Page said he wrote songs to change the world and many people in the 1970s and 1980s believed the songs being sung by Christy Moore and the lads and lassies were changing ideas about the world we were living in.

It wasn’t to be.

The likes of Page might be the last of their kind, Christy Moore and all those who wrote songs for the Hearts probably are. The writing was on the CD sleeves in the early noughties. “I don’t care if your heroes have wings, your terrible beauty has been told.”

Americans Eve Cassidy, Dolly Parton and Alison Krauss got to appear on A Woman’s Heart – A Decade On, and everything had changed, just when we thought the next Irish generation would emerge with those new ideas to perform songs with generation-changing lyrics.

Who, now, will write about the 21st century Allende: “It’s a long way from the heartland to Santiago Bay, where the good doctor lies with blood in his eyes and the bullets read US of A?”

Who, now, will explain why there is no time for love in the morning? “You call it the law – we call it apartheid, internment, conscription, partition and silence.”

Who, now, will tell our history: “We are a river flowing.”

• Jim Page arrived around the time of the anti-nuclear protests at Carnsore in the late 1970s

A new wave

Americana is a term associated with a type of music from North America. It is not easily defined. The tag emerged in the late 1990s as a marketing tool for a ‘new wave’ of American music.

The Coen Brothers film O Brother, Where Art Thou? gave it credence through the acoustic guitar sound of Norman Blake and John Hartford, and gave it substance with the soothing voices of Alison Krauss and Gillian Welsh, musicians hardly heard of in their own country at the time.

As a musical genre, Americana ran much deeper, back to Appalachian, Latin-American and Afro-American influences.

Deliverance, John Boorman’s cinematic interpretation of James Dickey’s novel set in the Appalachians, introduced a banjo tradition that was as rustic as it was rebellious. It wasn’t folk music and it certainly wasn’t country and western, or country and folk. It was something different. It was called bluegrass.

It was also the beginning of a realisation among Americans that their world was being manufactured. These days they call it cinematic licence. The banjo-playing boy in the film could not play the banjo, he merely played an ersatz role. The banjo was played by a musician called Mike Addis and the tune was called Feudin’ Banjos, written in 1955 by a guitar player called Arthur Smith.

When Smith heard his music on the film he demanded compensation and royalties and recognition. The film company offered $15,000. Smith sued and got a settlement plus the royalties from what was now called Duellin’ Banjos but he never got the recognition.

Other musicians, fearing that their rustic music would also be colonised, became smart overnight. They demanded their rights and royalties. So when musicians like Mike Nesmith (best-known for his role in the television series The Monkees) watched as singer Linda Ronstadt, in her Stone Poneys days, recorded his song Different Drum, he never feared he would not get royalties when she became even more famous than him.

• (Clockwise) Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, Iris Dement and Jim White

Madison marketing men

The marketing men of Madison Avenue, especially those who got involved with the film and music industries, had a different attitude. It was all about image and money. At the beginning, Americana became a device to sell America. Then it became something else – the “colonisation” of culture.

The good musicians associated with Americana in the early noughties were unconventional. They were people like . . .

Texan Steve Earle – “I want what’s over that rainbow, I wanna get out of here someday” – who wrote about elicit whiskey, fearless hearts, hard women, lost highways and working life;

Milwaukeean Jim White – “I wonder, baby why don’t you cry?” – who wrote about despair, disaffection and disillusion, apathy and irony;

Louisianan Lucinda Williams – “You drink hard liquor, you come on strong, you lose your temper, someone looks at you wrong” – who wrote about life and longing, and the ghosts of the Deep South;

Missourian Iris Dement – “We call ourselves the advanced civilisation but that sounds like crap to me, and it feels like I am living in the wasteland of the free” – who wrote about truth and reality, people and place.

This was real life, an antidote to the genre that was being misappropriated by copywriters, creative directors and compliant journalists.

Much of the rest of what was themed Americana was mediocre. Nesmith said it: “You and I travel to the beat of a different drum.”

And if Jim White could see the irony two decades ago, Steve Earle can hardly miss it now.

Galway Girl was mocked by the teenagers of Galway and Mayo when it filtered into the public consciousness in the mid-noughties. Used to the rustic sarcasm of The Saw Doctors, the girls (who knew what it was really like to be a Galway girl) rewrote the lyrics. They seemed to be saying, ‘Feck ya, here’s our reality!’

It was obvious, back in the 1960s, when the ‘hidden persuaders’ on Madison Avenue started to manipulate minds, that it would only be a matter of time before everything creative would be used to sell ‘objects of desire’.

• Sharon Shannon

They’re back

Canadian Marshall McLuhan coined the phrase “the medium is the message” and predicted that one day we would all live in a “global village” designed for one purpose.

The ancient Romans used “bread and circuses” to manipulate the people; today the modern Americans use music, media and technology, which they control with an iron fist.

What does Leo Hallissey think?

When Steve Earle was roaming the pubs of Galway City, Hallissey wondered about the impact.

“When you pick up the phone you hear a mid-American accent, that disembodied speech. They’d be better off putting tape recorders on us. Those dehumanising aspects of so-called progressive Ireland, the shapers and makers. I don’t like that slick marketing. It makes me uneasy. It also devalues slower, deeper, older kinds of things.”

Sounds about right.

Now the Americans are back, attracted to the West because one of their own wrote a song that became a global hit. Sadly that is not going to happen to songs about dreamers, revolutionaries, the faithfully departed . . . and bogmen!