16 January 2017 Edition

Fr Michael O’Flanagan and the Roscommon by-election

Remembering the Past

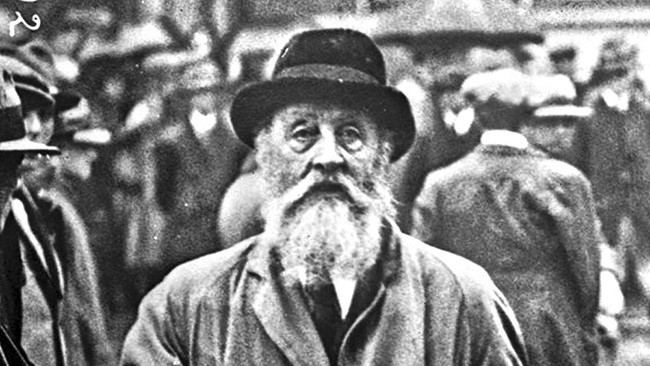

• Fr Michael O'Flanagan – No one had the least hope of victory except him

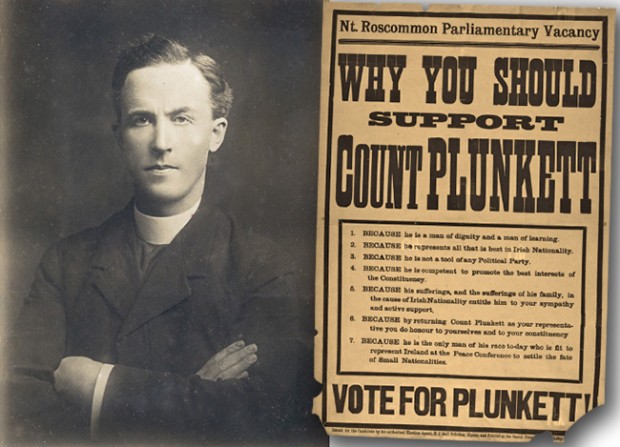

‘I deny the right of England to an inch of the soil of Ireland’ – Count Plunkett

BY JANUARY 1917, many of the hundreds of Irish political prisoners interned in Fron Goch Camp in north Wales had been released. But many were still imprisoned in England. Others, like Count Plunkett, were legally excluded from Ireland.

Plunkett had been deported to Oxford after the 1916 Easter Rising. Not previously very active in politics, George Plunkett, a Papal count, came to prominence after the execution of his son, Proclamation signatory Joseph. He was summarily dismissed from his post of Director of the National Museum.

In December 1916, James Joseph O’Kelly, Irish Party Westminster MP for North Roscommon since 1885, died and a by-election was called. The prime mover in having a republican candidate stand in the election was Fr Michael O’Flanagan. A radical priest based in Sligo who was originally from Roscommon, O’Flanagan had supported workers’ and small farmers’ struggles. In 1915 he officiated at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in Dublin.

Fr O’Flanagan later wrote that the unanswered question before the by-election was whether “the example of the inspiration of the men of 1916 or the terror caused by their defeat would have the greater effect”. He initially approached Michael Davitt (son of the Land League founder) but he declined to stand. O’Flanagan then proposed Plunkett as the candidate and he agreed to run.

Geraldine Plunkett Dillon wrote that her father “came home from Oxford without waiting to be permitted to do so” as soon as it was decided that he should contest the election: “No one had the least hope of victory except, perhaps, Fr Michael O’Flanagan, who would not have anything else. It was too much to hope for!”

Backing Plunkett was a range of groups, including the Irish Volunteers, Sinn Féin, the Irish Nation League (an anti-partition group), people active in the Irish National Aid and Volunteers Dependants’ Fund, and defectors from the Irish Party such as Laurence Ginnell, MP for Westmeath. While often cited as the first Sinn Féin election victory after the Rising, Plunkett was not officially a Sinn Féin candidate. At that time the party was still controlled by Arthur Griffith and did not adopt a republican constitution until later in 1917.

Plunkett’s candidature was symbolic, given his son’s execution, but the politics of the campaign were clearly expressed by Fr O’Flanagan who spoke at venues throughout the constituency. He condemned the Irish Party’s support for the imperialist First World War, urged land reform and endorsed the men and women of Easter Week.

• Count George Plunkett

With much talk from the British Government and press about the “freedom of small nations” to justify the war in mainland Europe, O’Flanagan demanded that “the freedom accorded to Ireland be the same as that of Belgium, Serbia, Bohemia, Romania, France and Germany”.

Warning of the danger of conscription, he said it was “better and easier for young men in Ireland to carry their fathers on their backs to vote for Plunkett rather than to have to serve as conscripts in the trenches in Flanders”.

As the campaign proceeded, the country was covered in huge drifts of snow, earning it the name “The Election of the Snows”. This proved no obstacle to O’Flanagan. He organised parties of young men to clear the roads. He later wrote of the 24-mile stretch from Ballaghadereen to Strokestown:

“They worked like Irishmen whose heart is in their work. In two days the way was clear. Motoring between these two solid walls of snow, I was constantly reminded of the energy expended.”

The Irish Party and the pro-British press dismissed Plunkett’s chances. The Irish Times declared: “Count Plunkett is a person of no importance.” But as polling day approached it was clear that O’Flanagan had co-ordinated a massive effort. On the day, transport of all kinds was organised and Irish Volunteers were present at the polling stations. Many released prisoners took part and a chastened Irish Times admitted that “against this combination, Mr Redmond’s election machine simply went to pieces”.

Polling day was Saturday 3 February. At close of polls the ballot boxes were taken to Boyle, where they were guarded, by both the Royal Irish Constabulary and Irish Volunteers.

Fr O’Flanagan wrote:

“All night long, a body of police representing the British Empire sat on one side of the boxes and a body of young Volunteers representing Irish Ireland on the other.”

The count took place on Monday 5 February and at 2pm it was declared that Plunkett was the winner with 3,022 votes, as against 1,708 for the Irish Party’s Thomas Devine and 687 for Independent Jasper Tully.

Speaking to the jubilant crowd outside Boyle Courthouse, Plunkett said he would not be taking his seat in Westminster:

“My place henceforth will be beside you in your own country, for it is in Ireland that the battle of Irish liberty will be fought.

“I recognise no parliament in existence as having a right over the people of Ireland, just as I deny the right of England to an inch of the soil of Ireland.”

Again it was The Irish Times that commented prophetically when it said the Irish Party would be “swept out of three quarters of their seats in Ireland by the same forces that carried Count Plunkett to victory in North Roscommon, believed to be so peaceful and so free from Sinn Féin and the rebellion taint”.