1 December 2016 Edition

True confessions of an Eco-Warrior

• Robert Allen (second left) and fellow activists relax on Brighton Beach

‘Murky’ and ‘Lurky’ are warming their hands by the fire . . . They are stoned

“THE WORLD is my idea,” said 19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. “No truth is more certain, more independent of all others, and less in need of proof than this, that all that exists for knowledge, and therefore this world, is the only object in relation to subject, perception of a perceiver, in a word – idea.”

That world idea once became a quest and for a time it was so engrained in the collective consciousness that it was no longer the idea of one, it was the idea of many, like a meme.

That idea was “social ecology” but no one knew it by that name. Everyone else, however, knew that the followers of this weird idea were called “eco-warriors” and nothing could have been further from the reality than this glib misrepresentation.

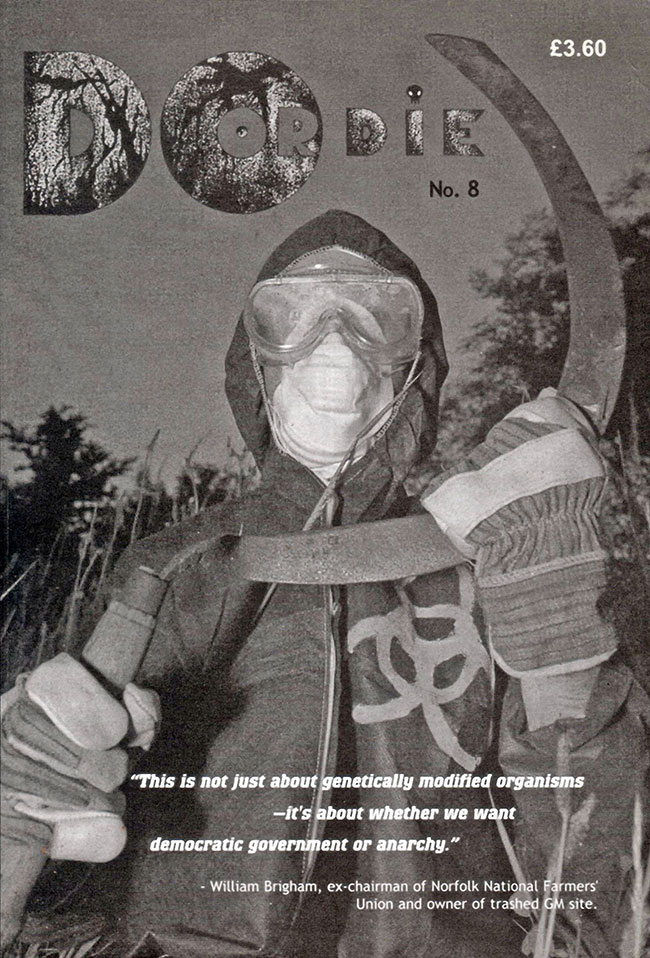

The problem lay in the image, the one that was projected onto people who engaged in the planning, execution and awareness of non-violent direct action (NVDA) – the one that the people themselves displayed to the world and the one that was perpetrated by those who were false.

We are in a woodland (not an unusual occurrence during the 1990s when non-violent direct action was at its height across the world). The incessant rain has finally stopped, leaving a glistening sheen on the sylvan canopy that glows under a joyous full moon – a moon so bright it casts dappled light on the forest floor.

Woodsmoke swirls like foggy mist in the foreground. Three silhouettes hunch in a circle around a well-stocked fire, red embers reflected in their eyes. The whole scene is surreal, possibly ironic, almost pagan-like.

‘Murky’ and ‘Lurky’ are warming their hands by the fire. They are stoned, slumped over. ‘Jerky’, the third figure, is sleeping, snoring gently, occasionally rolling his head as he appears to awaken before falling back into dreamland. In his last moment of consciousness, Jerky sees a pair of tittering wood fairies cavorting near the edge of the tree-line. In a soothing child-like voice he beckons them to draw nearer. Murky and Lurky are ignoring him.

The bare wooden chairs they are sitting on sink into the mud that surrounds the fire. Steam is rising from a cauldron resting uneasily on a wire mesh held in place between an unsteady structure of breeze blocks. Time seems to expand and contract in the night hours, as Murky and Lurky stare at the fire, talking quietly to each other. They are partially sheltered by a large tarpaulin that has been stretched over an interwoven pattern of tree branches.

Murky says, “Did ye get any seeds?”

Lurky, poking the fire with a long thin stick, mutters, “Yeah”.

“What are ye doing with them?”

“I’m going to plant them, what do you think I’m going to do with them? Tomorrow I’ll get some planks and make a small nursery.”

“If we’re here tomorrow, that is.”

Lurky, still poking the fire, becomes serious. “You think they’ll come in the morning?”

“There’s every chance of it,” says Murky.

Lurky, pushing the stick into the mud, asks, “Where is everyone . . . if we’re in danger of being evicted?”

“Feckin’ stoned, the bastards, like they always are.”

Lurky gets up, walks to the back of the bender, where he locates a cup and a tea bag. He says loudly, “You're very hard on everyone.”

“I’m not hard, I’m realistic. What are we here for? Tell me that? We’re here to protect this place, to stop the bastards cutting down the trees, destroying everything. You . . .”

Lurky, sitting down, says, “Are we not doing that?”

“Are we feck. We’re creating another cosy little elite. Most of the people here are control freaks or trying to find ways of making money or trying to escape from themselves. They’re fucked up, most of them, especially that fecker from Lisburn. He’s a plant, I tell ye. He’s too good to be true. He’s only interested in himself. He gives himself away.”

Lurky opens a tap near the bottom of the cauldron, letting steaming water into his cup. “You’re always going on about him. You think he’s being paid to be here?”

“I don’t know. I mean, feck it, this isn’t the place for politics. It’s meant to be a vigil, a presence. We’re supposed to be guarding the place, not setting up a feckin’ commune full of politically correct, socially fucked-up hippies.”

At that moment, a sleeping Jerky interjects, “Please don’t go away – I love you,” and begins snoring softly. Suddenly he awakes. “How’s it goin’?” He asks in a cheery voice.

Lurky, stretching his arms into the sky, says, “We're doomed.”

Such a scenario was not unusual in the years when woodland vigils, like the Village in the Sky outside Blackburn, sprouted like miraculous seeds and were cut down as young saplings just when it seemed they would grow into something wondrous. Historians now claim that the anti-road campaigns of the 1990s were a success. At the time they felt like defeat.

The Under-Sheriff of Lancashire claimed that had the Village in the Sky lasted one more week, construction of the motorway would have been halted. It did not last because of the divisions among the hippy “eco-warriors” and the serious “activists” (not that anyone seriously considered these labels) and because of malnutrition and police violence.

In the 1990s, especially in England, the majority of people who concerned themselves with the ecological and social issues of the times were college kids espousing veganism and the ridiculous idea that the Earth should come First! Most of them didn’t last.

The tactic of the Under-Sheriff, his bailiffs (Scouse bouncers from Blackpool) and the special police force that was sent up from the south was to arrest everyone who looked like a hippy and bail them “off site”. They were arraigned in Blackburn police station and when they were freed they turned right outside the police door and headed down to the bus and railway stations. We met these poor wretches with tea and chips and tried to persuade them to continue, to no avail.

By the middle of the decade it was obvious that not everyone with hippy sensibilities was cut out to be an NVDA activist. The hardcore, however, were different, and largely they were anonymous.

The summer of 1995 was very hot, and not just because of the climate.

“Actions” took place every day, sometimes more than once. The targets varied. Most were single actions rather than collective vigils. They were meticulously organised following a system that had been developed by Manchester Earth First!

Usually one person planned an action, completed the necessary preparation and reconnaissance, and then quietly gathered a crew of experienced people. Occasionally, an action could be planned by a small group but this was always seen as dangerous because of the fear of infiltration. If you were asked to “go on an action” you had two options – yes or no, and only when you said yes were you told what the action entailed.

It was known that an elite ‘task force’ had been established by the police in Southampton, dedicated to gathering information on the hardcore activists. Most of their attention centred on the animal lovers because these hunt saboteurs favoured violence of a kind that endangered lives. By the end of the decade this task force had the “real” names of some hardcore activists, but not all. Most activists used nicknames to protect their identities or were given pet names.

The best protection, ironically, were the cliques that emerged from the Manchester system. This system produced one of the most iconic actions of that era, the weeding of genetically-engineered sugar beet in Carlow, an event that has remained shrouded in myth and mystery.

In reality a crew was recruited in London and only those who participated in the action knew each other’s identities. They hired a van, travelled to Wicklow, stayed in a prearranged location, made a reconnaissance to Carlow (gardaí providing the directions to the farm!), returned that night, weeded the field and then left for England.

This was a very clever action. Its success was built on experience, reputation and trust. There was a plan and it was carried out to perfection. Sadly, it marked the beginning of the end for that generation of hardcore activists. What came later was a facsimile that quickly became distorted.

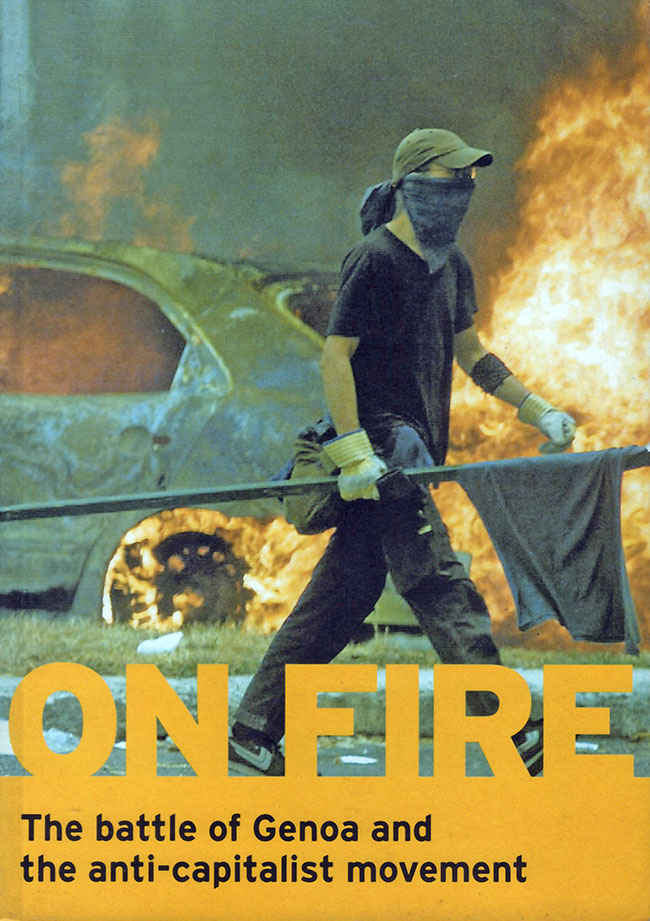

Several events presaged the end. One was the emergence of the People’s Global Action, its obsession with eco-anarchism, summit hopping and the vanity of its own actions, largely showcased in its independent media. Another was the tragedy that was Genoa. Yet another was that wandering image, which saw its expression at the Glen of the Downs.

Organised by two Irish activists who kept low profiles throughout the campaign, the attempt to protect this unique Wicklow woodland degenerated into chaos.

The true image of the so-called eco-warrior was seen at another successful action during the mid-1990s, this time in Huddersfield in the north of England, where the environmental officers of the local authorities met for their annual shindig.

Two activists, dressed in everyday smart clothing, penetrated the defences of the organising committee, created the conditions to let a bus-load of activists enter the building, disable the electrics and dump “toxic” waste on the stage.

There were many actions like that – plain-clothed and unassuming. And then there were some that were ill-timed and wrong. A group of activists inadvertently caused the closure of a McDonalds in downtown Swindon but upset the birthday plans of a 14-year-old girl. The tearful birthday girl confronted the leader, unable to understand what had happened. Sadly, the adult activist could not explain, instead deriding the girl for her discomfort.

Not everyone got the idea that changing the world without taking power (Dublin-born professor John Holloway’s much-lauded assumption) would not be a simple process. Most of those who claimed to want to change the world were too vain, and too gullible. And had never read Schopenhauer.