1 November 2016 Edition

Full and Plenty

Colonisation is not unique to Ireland but the loss of our food culture is

• In the 1960s, Maura Laverty told cooks to take seriously food preparation, baking and cooking

Ireland is a million light years away from the type of new cuisine being practised in the Nordic countries, where everything must be fresh and local

IT STARTED more than a generation ago in places like Danaghers in Cong, The Dubliner in Dublin, O’Dowd’s in Roundstone, in numerous cafés and restaurants in Belfast, Cork and Dublin, and in rural areas where there was a demand for a hearty midday meal.

Full and plenty only told part of the story. Locals knew where to go to get a mighty feed. It was the tourists and travellers who decided there was nowhere to eat. If asked, “Where can I get good traditional Irish food?” the response was enigmatic.

People knew who employed crazy cooks and competent chefs on their premises and as the 1980s descended into drudgery the very idea that Irish society knew how to cater for discerning tastes was left hanging in the air, under sodden skies and soft rain, always more reliable.

And that was the issue. The plates of food served in places that represented the trade were hit and miss, the quality unreliable, the taste insipid. There was nothing sensory about the experience.

The majority of people could not afford to eat in hotels, especially in the big houses with their arrogant manners and holier-than-thou attitudes. Occasionally, the word got out that a particular hotel had found a great young chef, and forays were made to check out the assertion. Usually, it was hyperbole.

It is hard to believe today that the majority of food available in cafés, hotels and restaurants during the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s was usually inedible. It was terrible. And the terror did not end there. The emergence of fast-food outlets in the cities and larger towns depressed those who could see no bright culinary horizons. Comfort food it might have been; rich in minerals and vitamins it was not. Generally, it was fatty and starchy.

• Sourdough bread is now prominent throughout the food cultures of Europe

Food historians, restaurant critics, time-served chefs and zany cooks have blamed everyone and everything for this sad scenario – from bad teachers to lazy proprietors to idiotic government regulations to the second coming – without getting to the root of the problem.

Throughout history the produce of this land has been exported. And with a ruling class disinterested in anything other than their own pathetic, outdated beliefs and traditions, the plain people of the country were never given a chance to develop an indigenous food culture that reflected the geography and landscape, a way of living that had not changed that much over the generations.

Black pudding, one of Europe’s oldest recipes, accompanied bacon and eggs in one form or another for breakfast, ‘The Bookie’s Sandwich’ – steak pressed into two pieces of bread – went with the dispossessed and is now a traditional dish of the Americas.

The capricious mackerel of the west and south-west were fished offshore and served pan-fried anytime of the day. Clams, cockles, mussels, oysters and scallops were consumed according to availability and fashion. The fruit cake was boiled long before it was baked; hams were baked and boiled (and hardly ever cured).

Langoustines (and crawfish) were no longer cooked on the boat (a tradition lost throughout the world, not only in Ireland). Liver from various animals was cooked with onions (a tradition that has remained sacrosanct in Venice and the Po Delta in Italy, and in several other places).

• Air-dried fish was once a tradition of all the Atlantic Fringe countries

Meat and potato stew with mutton rather than beef was always popular (reinvented in northern England as meat and potato pies). Oatmeal found its way into numerous preparations (just as it has done in every food culture dependent on grains for sustenance).

Potatoes with buttermilk or kale were preferred to potatoes in their skins or potatoes made into cakes. Raw-milk cheeses continued a culinary line back to antiquity.

Sea vegetables such as carrageen, dulse and kelp played a big role in baking and cooking. Scallions and leeks spiced up mashed potatoes but were also essential ingredients in soups and soda bread. It remains iconic.

Most of all it was fleshy fish – haddock, hake, herring, mackerel, salmon, sole, trout – that defined the food culture until all of it became a commodity and a luxury.

Wild forager food, from berries to mushrooms, always supplemented the diet.

Somewhere along the timeline, the tradition of air-cured and air-dried products was lost, while pickled, salted and smoked foods gained prominence.

Most of what existed in the ancient food culture of Ireland began to disappear 800 years ago and what has remained is now contaminated by ‘big house’ traditions and the remnants of Anglo-Norman, English, French, Norman, Polish and Saxon influences.

It is easy to say now that, at the same time the stories of legend were being written down, someone should have thought about the oral food tradition and recorded the habit of passing recipes from mother to daughter. Now the recipes we use are hardly indigenous and native. The arrival of the potato, the change from sheep to lambs, the gradual giveaway of the Atlantic, Celtic and Irish Sea fisheries and the mass migrations changed all that.

Colonisation is not unique to Ireland but the loss of our food culture is. All the post-Yugoslav and post-Soviet countries and regions have in less than one generation reclaimed their food cultures.

That we started to reclaim ours around the same time means nothing today.

• Michael O'Connell fishes Galway Bay for lobster that is then sent to France

Bord Bia and the new bourgeoisie who think they control the pulse of culinary life in modern Ireland will argue that their farmers' and street markets, food festivals and taste events suggest a different reality. They will point to the number of food artisans, gastro-pubs, specialist food shops, themed restaurants and the improvement in the standard of cooking, the quality and skill displayed by chefs who have earnestly learned their trade.

As any of those chefs will tell you, working a shift in a busy hotel or restaurant is tough. Good chefs who know exactly what they are doing are still thin on the ground. The best ones are coveted, and many of the really good ones emigrate.

And those who know what they are doing all repeat the same mantra: Ireland has no indigenous food culture. It is a million light years away from the type of new cuisine being practised in the Nordic countries, where everything must be fresh and local.

Of course, these days much of the blame for this is laid at the executive offices of the supermarket chains. Although Supervalu has attempted to introduce local products into its stores, the foreigners we know as Aldi, Lidl and Tesco dominate and control the market, importing vast amounts of produce to the detriment of the home-produced varieties. Sadly, local produce always costs more than the imported brands.

It might be argued that this is all we can expect from a free market economy and that any food industry – whether large or small, foreign or native – must compete. Strange that this does not happen in continental Europe, where EU and non-EU countries have embraced both the concept and the reality of the need to have a strong traditional food culture in every region.

This year saw a very successful Tastes of Donegal event. At the same time, a similar event for Galway failed to get off the ground, despite the fact that next year Galway will be one of Europe’s gastronomic regions.

To a magician it is all smoke and mirrors, perspectives and unrealities; to those who care about Ireland's nascent indigenous food culture, never mind its food sovereignty, the reality is pitiful and the future is written.

• Mackerel caught off the western seaboard remains a traditional food

It is a far cry from the days when The Dubliner opened a lunch-time kitchen to serve bowls of coddle to people who remembered it from their childhood, when Danagher’s served large chicken dinners to starving bachelor farmers and hungry young sport heroes and O’Dowd’s realised that their traditional fish dishes were the talk of the town (and much of the world beyond).

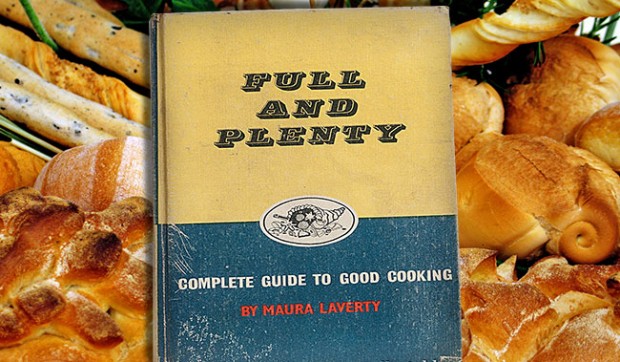

In the 1960s, Maura Laverty was cajoling home cooks to take seriously the art of food preparation, baking and cooking. She was ahead of her time because she recognised what north European and west Asian food cultures have always known – breads (and cakes) are the staff of life.

In her Full and Plenty cookbook she announced that bread-making was her culinary credo. “Soda bread is the traditional bread of Ireland,” she claimed and went on to explain why yeast bakery would take its place. The few bakeries left that still make soda breads of various types are endangered. Factory-made supermarket breads predominate, despite attempts by some bakers to keep old traditions, Irish and other, going. Bakers making breads with sourdough are also few and far between.

She also said that “good ingredients are more readily available in Ireland than any other country in the world”. A generation later, those who realised this had begun to change attempted to revive all that was traditional about the indigenous produce of Ireland. Here we are today, two generations later, and it is hard to see where another food revolution is going to come from.

Not now that you can get a mighty feed of roast meat, chipped or mashed potatoes, sauce and vegetables in almost every pub. Hardly traditional – just full and plenty!