3 October 2016 Edition

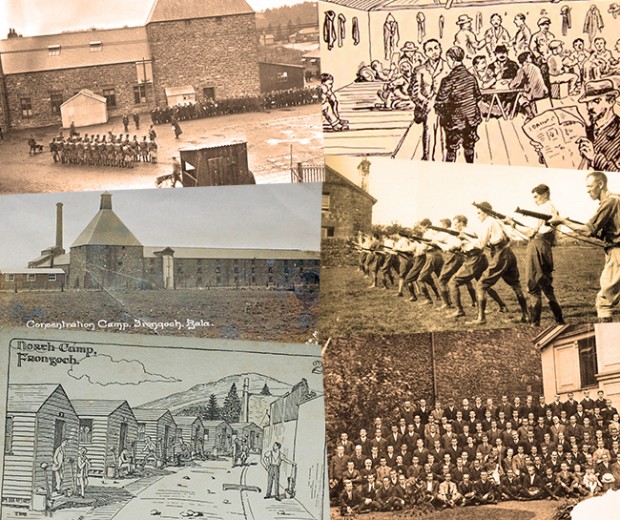

Fron Goch – Crash course in revolution

Remembering the Past

• Fron Goch helped to rebuild the IRA

It was the first time Irish political prisoners were held together in such numbers in one place

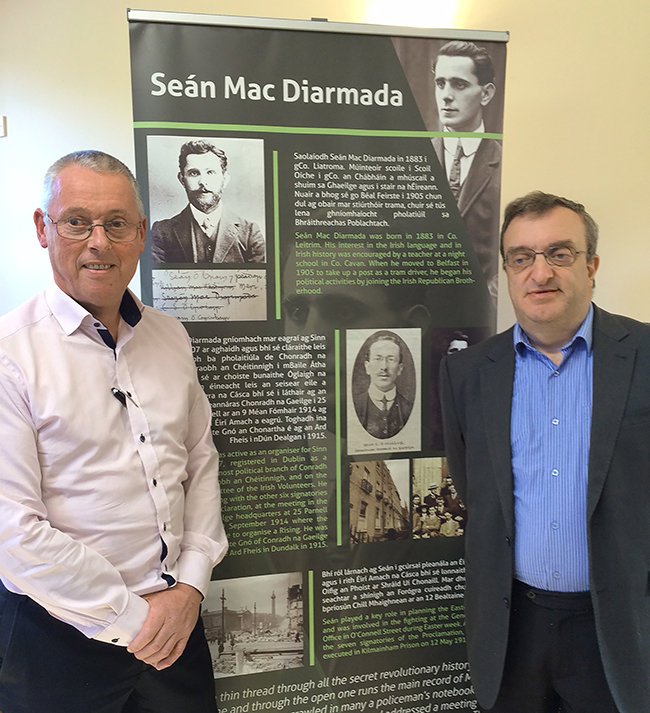

THIS ARTICLE is based ona talk given by Mícheál Mac Donncha in Mullaghdun Community Hall in County Fermanagh on 10 September 2016.

IT IS ESTIMATED that some 3,500 people were rounded up by the British Government after the 1916 Rising. About 1,500 were released shortly afterwards, leaving around 2,000. Of these, 160 were court-martialled; 90 were sentenced to death and 75 of these sentences were commuted to prison terms ranging from two years to life.

Fifteen republicans were executed by firing squad after courts martial – 14 in Dublin and one in Cork, and Roger Casement was hanged in London. The sentenced prisoners were sent to various jails in England. This left over 1,800 men who were not court-martialled but were interned without trial. Five women were held separately in English jails.

The internment camp was Fron Goch, near the town of Bala in north Wales, roughly halfway between Holyhead and Liverpool. The camp had been used to house so-called “enemy aliens” and German prisoners of war. It consisted of two camps. One was a former whiskey distillery and the other was a purpose-built compound with wooden huts.

Over the period from June to December 1916, 1,863 men were interned in Fron Goch. The men were sent across the Irish Sea in cattle boats or by train from prisons in England. Most had been held in Richmond Barracks and Kilmainham Gaol. Some had already seen their Easter Week leaders and comrades marched off to courts martial and executed. Many had played no part in the Rising.

The prisoners were taken by train to Fron Goch, which had its own railway station, previously associated with the whiskey distillery. They were divided between the two sections – the South or Number 1 Camp, which was the former distillery, and the North or Number 2 Camp, which consisted of wooden huts and service buildings.

The prisoners organised themselves along military lines with elected officers.

The prison regime had a strict timetable for meals, inspections, counts of prisoners twice a day and lights out but the men were allowed much latitude. They had free association, wore their own clothes, received parcels and visitors and were even allowed out of the camp on route marches through the countryside accompanied by armed guards.

One of the best accounts of Fron Goch is by Frank Robbins of the Irish Citizen Army in his book ‘Under the Starry Plough’ (Academy Press, 1977).

He recalled that on one route march the officer commanding the British armed guard was marching ahead and suddenly realised that he was at the head of the Irish prisoners instead of his armed patrol. While the majority of the Irish were fairly fit young men, the British soldiers were mostly elderly members of the Home Guard. It was a case of Dad’s Army guarding the Croppy Boys! The British camp commandant was known as “Buckshot” because he kept reminding the prisoners that the guards at the perimeter were armed with guns firing buckshot.

The prisoners organised classes in Irish history, the Irish language and other subjects. Fron Goch was in a Welsh-speaking area and many prisoners afterwards said that hearing the locals speaking Welsh so proudly gave the Irish an added incentive to make the effort to learn their own language.

• Sinn Féin MLA and former H-Block prisoner Seán Lynch (who spoke on Long Kesh 1976-2000) with Dublin City Councillor Mícheál Mac Donncha (who spoke on Fron Goch) at Mullaghdun, County Fermanagh

Robbins says that they had concerts practically every night and football matches during the mornings and afternoons. Rebel songs sung at those concerts by the Dublin men were eagerly learned by those from outside the capital and thus became popular and widespread during the Black and Tan period.

A football tournament for the Wolfe Tone Cup was played in Fron Goch that summer of 1916 in which Kerry had a one-point victory over Louth. Earlier this year, the GAA commemorated that match with a game between Hertfordshire and Yorkshire. It was played in the same field as in 1916, a field known to this day by locals as Croke Park.

Fron Goch brought together most of those who had taken part in the Rising as well as many who had not taken part but were in or associated with the Volunteers and Citizen Army.

1916 was unusual in that, unlike previous and subsequent armed campaigns, there was a general surrender of hundreds of insurgents to the British. In Fron Goch they were back together to share their experiences of before and during the Rising, while those from outside Dublin had the benefit of hearing first-hand about both the military and political aspects of Easter 1916. Networks and contacts were established, most notably by Michael Collins, and Fron Goch helped to rebuild the Irish Republican Army.

It was indeed a “University of Revolution”, although it was of such short duration it could probably better be called a 'Crash Course in Revolution'. It was only open for six months but in that time more than 1,800 men went through it.

The Fron Goch experience was very important in setting the agenda for republican prisoners ever afterwards. It was the first time that Irish political prisoners were held together in such numbers in one place and were so well organised. It was hugely significant in that it hardened resistance to attempted criminalisation or to any form of victimisation or isolation.

Robbins describes the prisoners’ organisation of themselves as:

“A blessing when efforts were being made by the prison authorities to select some of our colleagues for punishment or for conscription into the British Army. We made their efforts impossible by hunger strike and by refusal to answer roll call. It was our united action under our own leaders’ orders that convinced our captors that they were wasting their time and we were not to be coerced.”

Then, as later, when it suited the British Government they treated republicans as prisoners of war or as criminals or as political pawns. The new British Prime Minister Lloyd George took office in December 1916, and in 1917 he released the remaining Irish prisoners before reverting to criminalisation later that year.

The Fron Goch experience was probably among the least harsh and among the shortest duration for Irish political prisoners but it had a long-term effect in consolidating the republican prisoners’ sense of themselves as prisoners of war who would not be criminalised.