5 September 2016 Edition

The Blanket Protest begins

Remembering the Past

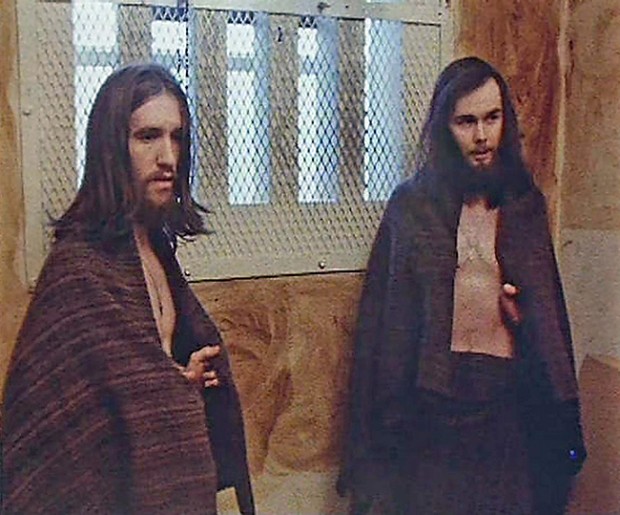

• As the cells filled in succeeding weeks and months, Kieran’s comrades followed his lead

‘They’ll have to nail it on my back’ – Kieran Nugent, September 1976

BY the autumn of 1976, the armed conflict in the Six Counties had been ongoing for seven years. The widespread imprisonment, ill-treatment and, in some cases, torture of nationalists by the British state fuelled the conflict and, as so often in Irish history, the prisons became a frontline in the struggle.

From August 1971, internment was imposed. It ended in December 1975 and during that period 1,981 people were locked up without any charge or trial; of that number, only 107 were unionists/loyalists.

But the end of internment merely signalled a new phase of British repression.

The British Government decided to end Special Category Status, which was effectively the recognition of republicans convicted in the courts as political prisoners – in other words, prisoners of war. This status had been achieved in May 1972 after a 35-day hunger strike by IRA prisoners in Crumlin Road Gaol.

The British Labour Government announced that those convicted after 1 March 1976 would be denied Special Category Status.

They would no longer be held in the Cages of Long Kesh, where convicted and sentenced republicans had been locked in compounds adjacent to those interned without trial.

Instead, the sentenced republicans would be moved to the newly-built H-Blocks of Long Kesh, the ‘Cellular Maze’ in official jargon. This was supposed to be a conventional criminal jail – “the most modern prison in Europe” as British Government spokespersons called it.

The purpose of the H-Blocks was to implement the policy of criminalisation which attempted to treat republican political prisoners as common criminals and, more importantly, to have the wider world see them as criminals. Internment and the ill-treatment of prisoners had done serious damage to Britain’s international reputation and a major propaganda counter-offensive, as part of a wider counter-insurgency strategy, was required.

• ‘They’ll have to nail it on my back’ – Kieran Nugent, September 1976

The British Government had been shaken by the heavy casualties suffered by the regular British Army at the hands of the IRA, with the knock-on effect of a growing sentiment in Britain itself towards withdrawal of troops from Ireland. A policy of “Ulsterisation” was introduced whereby the British crown forces recruited locally in the Six Counties – the paramilitary Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) armed police force and the Ulster Defence Regiment of the British Army, the largest infantry regiment – would be pushed to the frontline.

The RUC played a key role in arresting, interrogating and torturing suspects to secure convictions in the special juryless ‘Diplock’ courts. This process soon became what republicans called a “conveyor belt”, with the ultimate destination being a cell in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh.

It was the autumn of 1976 before the conveyor belt sent its first victim to a H-Block cell.

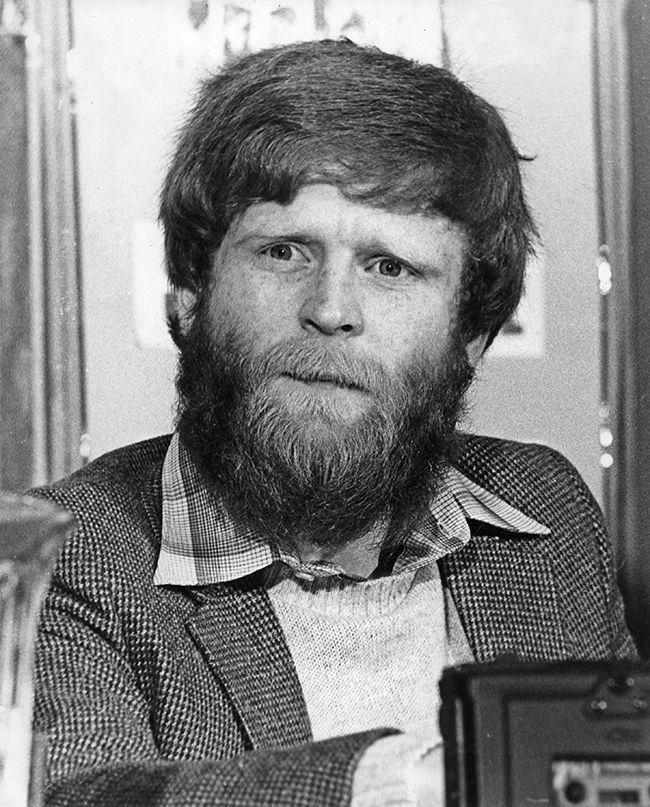

Kieran Nugent, from west Belfast, was only 18 years old but his life had been a microcosm of the nationalist experience since the conflict began. At 15 he had been wounded by loyalist gunmen in an attack in which he saw a friend killed. He joined the IRA, was jailed in Crumlin Road and later interned in Long Kesh until November 1975. Arrested again in May 1976, he was the first to be convicted after the 1 March deadline ending Special Category Status.

Kieran was brought to the H-Blocks on 14 September 1976. Without any prior instruction or organisation, but acting on his own defiant instincts and following the republican tradition of resistance to criminalisation, he refused to wear the prison uniform. (Convicted republicans prior to 1 March could wear their own clothes.)

His defiance was summed up in the words attributed to him when presented with the uniform: “They’ll have to nail it on my back.”

He was thrown naked into his H-Block cell and a prison blanket was thrown in after him. He wrapped himself in the blanket and so began the Blanket Protest.

• Blanket Protest tribute at the 2016 Hunger Strike commemoration

As the cells filled in succeeding weeks and months, Kieran’s comrades followed his lead. No one at the time could foretell that the protest would involve hundreds of prisoners over the next five years, culminating in the death of ten republicans in the Hunger Strike of 1981, after which the prisoners’ demands were ultimately achieved.

Speaking at Kieran Nugent’s funeral in 2000, Sinn Féin Councillor Tom Hartley said:

“Isn’t it wonderfully ironic then that the one major flaw in British strategic planning was their inability to read the minds of republican remand prisoners?

“In the cells of the Crumlin Road Gaol and Armagh Women’s Prison, young republicans had decided to resist any attempt to treat them as criminals.

“In the simplicity of his defiance, alone and in the vulnerability of his nakedness, Kieran refused to be broken. If ever we need an example of the power of the human spirit, we should reflect on that moment when the dignity of this young man broke the power and inhumanity of the British state.

“At that very moment with their first H-Block prisoner, when they thought themselves all-powerful, the British Government in Ireland had already lost their attempt to criminalise the republican people and their struggle.”

Kieran Nugent, the first Blanket Man, began the Blanket Protest in September 1976.