5 September 2016 Edition

A credible vision of unity has to be outlined – Chris Donnelly

UNCOMFORTABLE CONVERSATIONS

• Is making the North of Ireland into a viable and economically successful political entity a prerequisite to securing Irish unity?

At this historical juncture, I believe republicans, and all Irish unity advocates, are obliged to give serious consideration to what form Irish unity can and must take

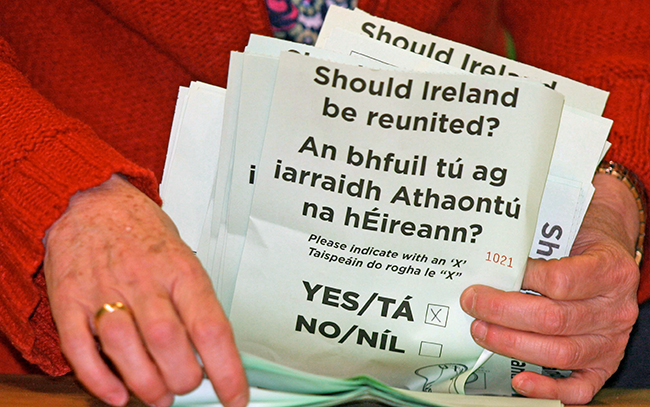

THE DECISION by the British electorate to plump for Brexit has provided a renewed lease of life for Scottish nationalists, whilst it has also encouraged many Irish republicans to outline the case for a Border poll in the near future. Even Taoiseach Enda Kenny and Fianna Fáil leader Mícheál Martin have made public pronouncements where they’ve spoken of the prospect of an Irish unity referendum at some point in the future.

At this historical juncture, I believe republicans, and all Irish unity advocates, are obliged to give serious consideration to what form Irish unity can and must take.

Sinn Féin stands alone as the only all-Ireland party today, and it is the success of republicans in building a nationwide party and political movement that is likely to compel political opponents to seek to emulate that approach by organising and seeking to represent people across all 32 counties.

Whilst this may provide unprecedented electoral challenges for republicans, it would be a most welcome development as it would mean a plurality of all-Ireland voices would exist to articulate the case for unity through political ideas and actions.

Developing and fostering all-Ireland politics is one thing, but if republicans are serious about mounting a winnable campaign in the forthcoming generation to secure Irish unity then the time has long since passed for a credible and tangible vision of what form unity would take to be outlined.

The Good Friday Agreement represented a historic compromise for Irish republicans and unionists, providing a political and constitutional framework within which national rights would be respected and power-sharing structures worked to reflect the reality of the divided society in the North.

Yet what was implicit and explicit in republican acceptance of the Good Friday Agreement and in the conduct of its ministers and elected reps in the 18 years since is that republicans now see making the North of Ireland into a viable and economically successful political entity as a prerequisite to securing Irish unity.

That statement might appear to stand traditional republican rhetoric on its head but, in reality, it has been the logical assumption driving mainstream republican strategy since Sinn Féin signed up to a Good Friday Agreement incorporating a Stormont Assembly and power-sharing Executive.

• There is a prospect of an Irish unity referendum at some point in the near future

Accepting that means recognising that the time has come for republicans to find a place within the united Ireland narrative for the perpetually-contested entity that is Northern Ireland. Another sacred cow for some but, for thinking republicans, one thing is clear: winning a united Ireland referendum will not be possible unless the vision of what Irish unity might look like moves from the abstract into the concrete. This includes dealing with how to address the reality of the rights and entitlements of the British and unionist people of the North.

To that end, I would contend that the answer is already with us.

The North is now, and will continue into perpetuity to be, a contested entity, a hybrid state peopled by stoutly and proudly Irish and British communities whose identities may overlap but may also continue to remain completely separate.

In order to address that reality and allow for the rights and entitlements of the Irish nationalist and republican people to be respected in a UK context, the Good Friday Agreement provided for constitutional and political architecture to respect all three strands of identities that pertain in this society: British, Irish and Northern Irish.

Winning a united Ireland referendum will involve demonstrating in a comprehensive manner how we aim to provide for the same safeguards for the British and unionist people.

The continued existence in a jurisdictional sense of the Northern state, with some regional powers, in an all-Ireland framework would allow for the minority rights currently existing for nationalists to be provided for unionists, removing the ‘fear’ of the unknown which always plagues those articulating the cause of constitutional change but also providing an effective means of ensuring that those more comfortable with a Northern Irish identity, multi-layered or standalone, would feel respected and attracted to a united Ireland model.

For republicans, recognising ‘Northern Ireland’ was once an anathema, akin to betraying the vision of the Republic, conceding the legitimacy of partition and surrendering our entitlement to be viewed as an integral part of the Irish nation.

In this post-Good Friday Agreement era, in which our all-Ireland identity has been and continues to be affirmed and strengthened, the time has come for republicans to find a place for Northern Ireland as part of the plan to finally deliver on the cause of unity.

Chris Donnelly is a former Sinn Féin council candidate, a political blogger and regular commentator on TV and radio.

Editor’s Note: Guest writers in the Uncomfortable Conversations series use their own terminology and do not always reflect the house style of An Phoblacht.