4 July 2016 Edition

Where only sport is sovereign

Between the Posts

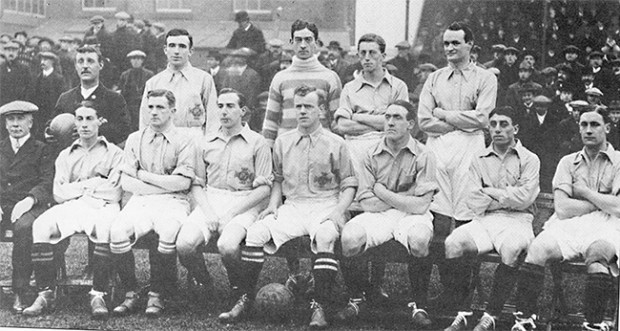

• Ireland team v Wales 1913–14. Back row: Hugh McAteer (trainer), Val Harris (Dublin), Fred McKee (Belfast), Davy Rollo (Belfast) and Patrick O'Connell (Westmeath). Front row: E. H. Seymour, Sam Young (Belfast), Billy Gillespie (Donegal), Alex Craig (Gal

It looks as though soccer has transcended the contradictions of conflict thrown up for the rest of us. Or has it?

A LITTLE BIT of Irish sporting history was made in summer 2016, although it wasn’t marked as such. Perhaps it stirred up too many contradictions. For never before have both soccer teams, North and South, reached the finals of the same competition. That was the history made in soccer’s Euro 2016 Finals.

Both teams were managed by O’Neills – Martin and Michael. Both men were brought up in the Six Counties. For both, their love of sport was fostered and flourished amidst ferocious political conflict. Both of them played Gaelic games in their youth before building prosperous careers in professional soccer.

I knew Michael O’Neill from my school days. He was a year ahead of me at St Louis High School in Ballymena. We enjoyed success together on both the school’s Gaelic football and soccer teams in those days. Our mid-winter training included scrambling up snow-covered slopes at the back of the school. Before sessions were over, the white surface would have become a slushy mudslide. More than one of our number would have been heaving up on the sidelines. But coached by Hugh Mussen from Down and Dominic Corrigan from Fermanagh, we grew together as a unit.

When we got onto the Gaelic pitch, Michael was a wing-half forward with explosive speed. He brought that athleticism, attitude and his own great football gifts into his career in soccer.

I don’t know Martin O’Neill but, by all accounts, he also enjoyed playing Gaelic football in his native County Derry. When the Six Counties team famously beat host country Spain in the 1982 World Cup Finals, Martin O’Neill captained that team. By the end of his international football career, he had 64 caps. Now he manages the other Irish soccer team on this island.

Seamlessly stepping from North to South as successfully as Martin O’Neill has, it looks as though soccer has transcended the contradictions of conflict thrown up for the rest of us. Or has it?

Like most aspects of life in Ireland, it wasn’t always this way.

Between 1882 and 1924, a single team represented the whole of Ireland. It was organised by the Belfast-based Irish Football Association (IFA). With the advent of partition in 1921, a Dublin-based group split from the IFA and badged itself as the Football Association of the Irish Free State (FAIFS). By 1953, FIFA had decreed that both teams, North and South, could enter competitive tournaments. By this time, the FAIFS had renamed itself the Football Association of Ireland (FAI).

Debate about having two teams on the one island have raged ever since.

Football legends as renowned as the late George Best, who played for the IFA (Northern) team are reported to have called for a single Irish team. In recent years, that concept has been raised in public again.

Yet controversy between the IFA and the FAI also ensued in relation to team selection, especially with talented players from the North such as James McClean electing to play for the South.

The use of a ‘grandparent rule’ also allows for people of Irish ancestry who have grown up outside this island being chosen for the Irish team. The argument for this seems solid enough given the forced migration of so many from Ireland over decades. Yet it has inspired critics to ask how Irish is the soccer team from Ireland.

Bias and bigotry have long hounded soccer.

I remember walking along the dark, narrow streets at the back of Windsor Park in my youth. My late father had got football tickets to take me and my two younger brothers to watch the Six Counties soccer team which Martin O’Neill captained. The atmosphere was ugly and alienating. We never went back.

In later years, the perceptible sectarianism took the form of death threats against Neil Lennon. As a result, he ended his international career.

Scenes from Euro 2016 gave cause for greater hope. Irish fans, North and South, showed solidarity with one another.

Ideas for a single Irish team once again may still be disputed but there are other unanswered questions.

When the Irish rugby team takes the international stage, comprised of players from all four provinces, a different anthem is sung. It’s a gesture which some have publicly scorned. Yet if “Uncomfortable Conversations” are ever to become “Uncomfortable Actions”, sporting symbols and songs to unify people may be required.

In rugby, cricket and hockey, people from North and South play together. Separate soccer teams is a reminder of division. As the two O’Neills illustrate, people in sport have multiple identities. How to recognise those subtleties in a single Irish soccer team requires more imagination.