5 January 2016 Edition

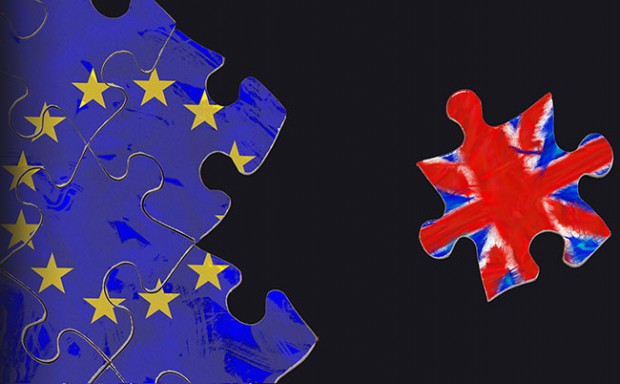

A British ‘Brexit’ huge implications for Ireland and rest of EU

Another Europe is possible – Treo eile don Eoraip

Funded by the European United Left / Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) – Aontas Clé na hEorpa / Na Glasaigh Chlé NordachaCrúpa Paliminta – Parlaimimt na h Eorpa

“BREXIT” – the partial disengagement or even full withdrawal by the British state from the EU (and formal repeal or significant erosion of human rights protections) – has hugely negative implications for Ireland, North and South.

Issues including the Peace Process, human rights protections, agriculture, jobs, infrastructure and energy, cross-Border trade and travel will be directly affected by a BREXIT.

A British exit would bolster partition, reinforcing the Border by an international frontier with possible passport checkpoints and customs controls, hindering free movement and disrupting the lives of nearly a million people living in the Border region.

A Brexit would mean no more Single Farm Payment or Rural Development Fund, no Structural Funds, and no PEACE Funding, with high human, social and economic costs. It is also unlikely that the British would replace the direct funding currently received directly from the EU. EU funding from 2007-13 was worth £2.4billion to the North.

Europe does need serious and radical democratic reform. Sinn Féin believes in strengthening the accountability and transparency of the European institutions but it is not in favour of a withdrawal from the European Union and completely oppose Brexit.

But what are the views of the other European member states?

Ever since British Prime Minister David Cameron announced in January 2013 that he would hold a referendum on a renegotiated British EU membership agreement, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has made no secret of her desire to keep Britain within the EU.

The German Government has a vested interest in keeping Britain in the EU, especially for economic reasons. Additionally, Germany also understands the symbolic value of Britain remaining in the EU. The acrimonious exit from the EU of such a significant member state would be a huge blow to the EU’s credibility. Berlin has already made perfectly clear that any changes to European treaties would be too risky.

Merkel’s government has set up a Berlin-based Brexit task force to troubleshoot the proposed reforms and she has reinforced her message of opposition to an exit with a call for Britain and Germany to remain “united and determined” in reforming the EU and promoting competitiveness.

Despite its strong interests to see Britain remain in the European Union, Germany will not cross every line to accommodate Cameron’s wishes. There are limits in substance and style to what Germany believes is acceptable.

Cameron and Merkel are firmly agreed that there should be no incentives for economic migrants, such as out-of-work benefits. But Merkel will not agree to quotas or special rules for Britain on this. The political message from Germany to Cameron is: ‘Pull out, and your country will find its position in the world reduced.’

Similarly, a British referendum on leaving Europe raises a number of reservations in France.

France would not want Britain to leave the EU despite its historical ambivalence toward Britain and their divergent views on Europe’s future. Britain remains a key partner and many in France see it as a valuable counterweight to Germany. France thinks that the union would be weakened by the loss of its second-largest economy, a global commercial power with significant diplomatic and military influence.

A new reform of the European treaties would be highly likely to fuel an intense public debate in France, perhaps even to be rejected if it were also put to a referendum. Former Cabinet ministers Laurent Wauquiez and Michel Rocard argue in favour of a Brexit (the latter considering that Britain is principally to blame for the paralysis in European decision-making); French President François Hollande is prepared to consider British demands for EU reform and could accept changes that simplify EU procedures and cut red tape.

Paris, however, is firmly set against any move to grant Britain opt-outs on issues such as the free movement of people, workers’ rights, environmental protection, or food safety rules. French leaders speak of how they want to see London stay in the European Union – but not at the expense of giving away lots of concessions to help Cameron.

Poland shares the same views and with between 500,000 and 800,000 Polish immigrants now settled in Britain, the British discussion has a Polish dimension.

• British Prime Minister David Cameron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel

One of the main slogans used by Prime Minister Cameron and the British anti-EU critics is the crusade against immigration in general and ‘social benefit scams by foreigners’. But with Poles now being the third biggest immigrant group in Britain, working hard and strengthening the British economy, Brexit advocates will find few allies on the Polish political scene.

Scaling back the free movement of people is going to be a red line for the Polish Government if the rights of Poles residing in Britain were undermined. It would easily become an issue in Polish domestic politics.

To Polish ears, the news that David Cameron intended to call a referendum on his country’s future membership of the European Union was like blasphemy. An active, outward-looking, and confident Britain firmly rooted inside the European Union is therefore clearly in Poland’s interest. Poland would be largely supportive of creating a good package of EU reforms that Cameron can sell at home as a success but, similar to France and Germany, it is not willing to give Cameron whatever he wants in order to keep Britain in.

In contrast, half of the parties represented in the Italian Parliament have run Eurosceptic campaigns. The Five Star Movement and Lega Nord have campaigned on the need for a referendum on the euro.

At the same time, the potential cost of failing to find a compromise with the British does not pass unnoticed. Since 2014, Italian exports to Britain have grown 9.4%, reaching a value of €9billion. Business relations are optimal and dozens of Italian companies – from Finmeccanica to Eni, from Merloni to Calzedonia, from Pirelli to Ferrero – are well-established in Britain.

The British want clothing, food, sports cars, furniture and domestic appliances from the Italians, as well as collaboration in the fields of energy, the military and aerospace research. In return, Italy imports cars, hi-tech, whisky, financial services and technology for renewable energy from them. If Britain leaves Europe, all of the rules that made this possible and mutually convenient would have to be revisited – and what happens then would depend on new rules and especially new tariffs.

Apart from trade relations, Britain’s net contribution to the EU is estimated to be around €13.5billion. In this respect, a Brexit would reduce the EU budget, making it likely Italy will need to pay more.

And, likewise with the Polish, the possible limitation for European migrants to move and work in Britain would have devastating social and economic consequences for Italy. According to the Office for National Statistics, 150,000 Italians resided there in 2014; in 2015, 57,600 Italians registered for British National Insurance numbers, which was 37% more than in 2014.

Spain also has no sympathy with the idea of distorting “the four fundamental freedoms” (the free movement of goods; the free movement of services and freedom of establishment; the free movement of people, including free movement of workers; the free movement of capital) until they become unrecognisable, just to pacify David Cameron’s Tories.

Both being controlled by conservative governments, Spain and Britain share similar interests in enhancing the single market, cutting red tape for small businesses, and being supportive of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership negotiations. The Spanish Government, however, cannot cope with any proposals whose goals would be to limit the freedom of movement in the EU or would directly restrict social benefits to Spanish migrants.

With up to a million Britons living permanently in Spain, the main Spanish political parties agree that, in the current context, any intergovernmental negotiation among 28 member states would be like opening a Pandora’s Box which has taken so much effort to manage over the past decade.

In Madrid there will be a certain flexibility to negotiate the exceptions that may eventually accommodate Cameron but it is not simply going to accept Britain’s desire to force all of its partners to negotiate a treaty which requires parliamentary ratification or referendums across the member states.

While many Eurosceptic Britons are quick to criticise the bureaucracy of EU membership, few are actually aware as to the actual cost of a Brexit. Leaving the EU will have large-scale financial consequences for Britain in terms of its future economic development and partnerships with Europe, while the EU will suffer significant political repercussions and a long-term identity crisis.

So while there is no question that Ireland would be hardest-hit by a Brexit with a huge setback for political and economic progress and continued democratic transformation of the North, as well as a fall of three billion euro in exports for the 26 Counties, the adverse effects are widespread across Europe.