2 November 2015 Edition

Prisoners of the past

Discrimination against republican and unionist political ex-prisoners contradicts Agreements

In 1998, the Irish and British governments pledged to ‘continue to recognise the importance of measures to facilitate the reintegration of prisoners into the community’

MARTIN NEESON, a republican political ex-prisoner, has been granted permission by the Belfast High Court to challenge a decision from the Stormont’s Department of Finance and Personnel that he was unsuitable for continued employment as a landscape gardener with conservation volunteers in west Belfast despite performing his duties without incident for the preceding 18 years.

The basis of his challenge was that the Department of Finance and Personnel acted “irrationally and unfairly in relying upon a conviction that was 40 years old in assessing the applicant’s character and suitability for continued employment”.

Restricted travel, restricted employment opportunities, barriers to adoption and purchasing of some goods and services define a life of exclusion for ex-political prisoners. This was compounded by the precedent established in the SPAD (Special Advisers) Bill which in effect sought to institutionalise discrimination against political ex-prisoners.

Engaging with this legacy question of political ex-prisoners in no way dilutes the need to engage with the pain, hurt and loss of all victims. That too is central to engaging with legacy. The issue of ongoing discrimination against political ex-prisoners, however, provides an insight into the wider challenge of how this society comprehensively engages with the reintegration into society of members of non-state armed groups.

In 1998, the Irish and British governments pledged to “continue to recognise the importance of measures to facilitate the reintegration of prisoners into the community by providing support both prior to and after release, including assistance directed towards availing of employment opportunities, retraining and/or reskilling, and further education”.

Eight years later, as part of efforts to restore the power-sharing Executive in the St Andrews Agreement (2006), it was again stated:

“The Government will work with business, trade unions and ex-prisoner groups to produce guidance for employers which will reduce barriers to employment and enhance reintegration of former prisoners.”

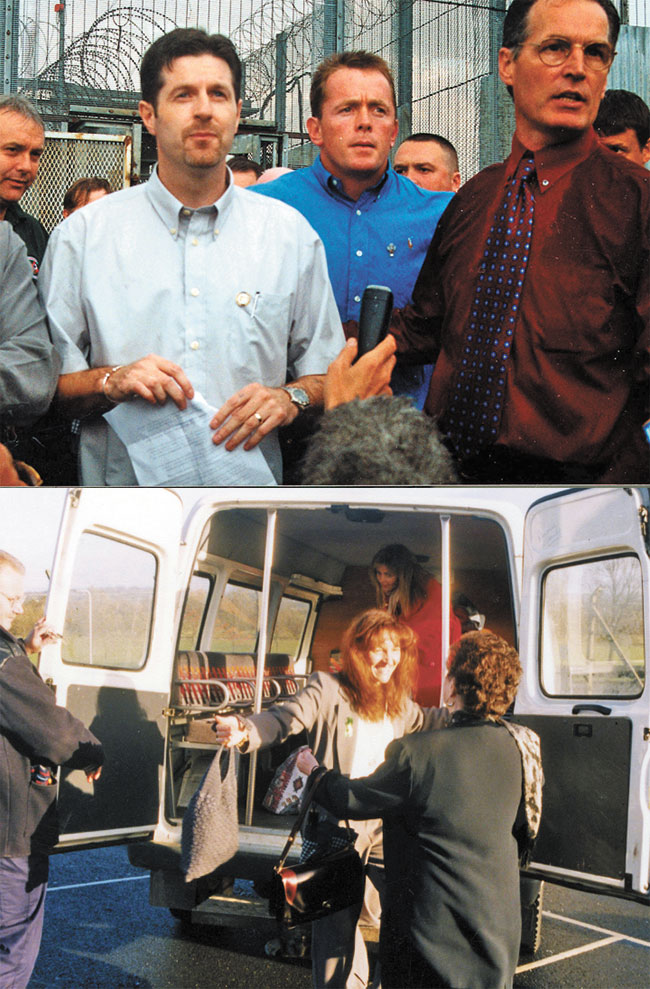

• Republican prisoners are released as part of the Good Friday Agreement

It is evident that, despite explicit commitments in the Good Friday Agreement (1998) and latterly the St Andrews Agreement (2006), little progress has been made to remove the barriers to participation in civic society for political ex-prisoners. This contrasts with the hundreds of millions of pounds paid to state actors, particularly former RUC officers who benefited handsomely from the Patten severance scheme.

The same questions remain as to how to engage with the legacy of imprisonment and its continued impact through discrimination. How are these men and women reintegrated back into community and public life?

Many of the political ex-prisoner groups, republican and loyalist, make a significant contribution to building the future. Many are acutely aware of the efforts of Coiste na n-Iarchimí, the republican ex-prisoners’ network, in terms of leading internal dialogues, and outreach to loyalism and British armed forces personnel. They have been actively involved in managing the peace, involved in providing support programmes to ex-prisoners and their families, and providing key services to those experiencing hardship through provision of welfare advice.

• Former POWs now MLAs: Martin McGuinness, Carál Ní Chuilín, Gerry Kelly and Jennifer McCann

There is no doubting that Martin Neeson, like many thousands of republican and unionist ex-prisoners, feels the personal burden of unresolved and unhonoured political commitments to deal with barriers to employment for ex-prisoners.

Twenty years into the Peace Process, hard questions need to be asked about where are the “measures to facilitate the reintegration of prisoners into the community by providing support both prior to and after release”? Furthermore the question needs to be asked of Stormont departments within our power sharing Executive why is discrimination against ex-political prisoners being tolerated despite outstanding peace process commitments?

If we are serious about building a shared future, surely it is now also time to end designation of political ex-prisoners as a Section 75 group, which would basically mean they cannot be discriminated against on basis of past imprisonment.

The denial of rights to political prisoners is an equality issue – a human rights issue that requires resolution.