1 September 2015 Edition

Book Reviews

Over 30 different colonial wars are itemised, establishing an unbroken line of expansionist conflict by the major imperial nations in the run-up to the First World War

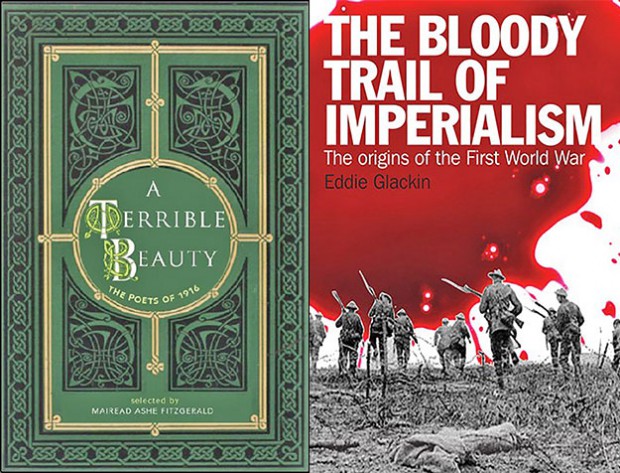

Rhyming and the Rising

A Terrible Beauty – Poetry of 1916

Selected by Máiréad Ashe Fitzgerald

O’Brien Press, €14.99

Review by Mícheál Mac Donncha

PÁDRAIG PEARSE famously remarked that if the Rising would do nothing else it would rid Dublin of three bad poets. But Pearse himself, Thomas MacDonagh and Joseph Plunkett were three fine poets and their poetry lives on, inextricably linked to their leadership of the Rising and their execution after it.

The complete poems in English of these three signatories of the Proclamation have been collected together before. This volume begins with a selection from each of them and then has selections from George Russell, Francis Ledwidge, W. B. Yeats, Eva Gore Booth, Dermot O’Byrne, James Stephens, Seán O’Casey, Thomas Ashe, Joyce Kilmer, Joseph Campbell, Dora Sigerson Shorter and Canon Charles O’Neill. The last named was parish priest of Kilcoo, County Down, and wrote the ballad The Foggy Dew, included here.

While Yeats has dominated the poetic response to the Rising he was not in sympathy with it. For me, the best poems in this book (apart from those of the three poet leaders) are by two contrasting figures. Francis Ledwidge knew Pearse, MacDonagh and Plunkett as friends and fellow poets, yet he was in the British Army. After the Rising he was increasingly out of place in that army and expressed his sympathy for the Irish cause in many poems. Eva Gore-Booth was sister of Constance Markievicz, but a pacifist. Like Ledwidge, she experienced the transforming power of the Rising, best expressed in her poem Easter Week:

Grief for the heroic dead

Of one who did not share their strife,

And mourned that any blood was shed,

Yet felt the broken glory of their state,

Their strange heroic questioning of Fate

Ribbon with gold the rags of this our life.

Waging war for wealth

The Bloody Trail of Imperialism: The Origins of the First World War

By Eddie Glackin

Communist Party of Ireland, €8

Review by Michael Mannion

THIS HIGHLY-READABLE history, published by the Communist Party of Ireland, is an obvious labour of love by Eddie Glackin who is a leading light in the party and a member of its National Executive Committee.

Glackin traces the imperialist histories of each of the major participating combatants in the century prior to the First World War and reaches the conclusion that the conflict was the natural, and inevitable, development of the policies pursued globally during this period.

The author introduces his book with Clausewitz’s famous aphorism “war is the continuation of politics by other means” and concludes the introduction with a quote from Lenin (no surprise there):

“The war of 1914-1918 was imperialist (that is, an annexationist, predatory, war of plunder) on the part of both sides; it was a war for the division of the world, for the partition and repartition of colonies and spheres of influence of finance, capital, etc.”

The rest of the book is filled with examples from the histories of the major powers that serve to confirm this interpretation.

There are two major schools of thought regarding the start of the First World War. One is that to which Eddie Glackin subscribes, namely as an inevitable extension of previous policies, as opposed to the alternative theory that it was due to an arbitrary combination of events that induced the participants to ‘sleepwalk’ into war without any real intention to commence protracted hostilities. The author’s contention is that the entire history of the various “Great Powers” was based upon the waging of war as “part and parcel of imperialism. It is in the nature of the beast. They cannot be separated.”

Outlining the establishment of the various nation states after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the book traces the rise of imperialist expansion throughout the world. Over 30 different colonial wars are itemised and serve to establish an unbroken line of expansionist conflict by the major imperial nations in the run-up to the First World War.

The author cites this as proving the predisposition of the “Great Powers” to conflict and therefore acted as precursors to the greater conflict of the First World War. No distinction is made between relatively small-scale conflicts with largely indigenous (and therefore poorly armed) peoples and all-out war with comparable nations and nation groups.

Glackin also follows the Marxist analysis by conflating imperialism and capitalism, although they were motivated by very different considerations. Many modern historians actually consider that the international business community, despite its many other failings, was in fact a force for peace. Global war is bad for global trade. International conflict destroys international trade.

Despite these quibbles, there can be no doubt that imperialism was certainly an important factor in the build-up to the war and this book provides a most interesting analysis.