1 September 2015 Edition

The bravery of the prisoners and the people

Jim Gibney, who was on the National H-Block/Armagh Committee in 1981, looks back at the prison struggle

‘The British state embarked on a policy designed to politically isolate Irish republicanism. Criminalisation – linked in a three-pronged strategy with ‘normalisation’ and ‘Ulsterisation’ and built on the torture of republicans in the various RUC interrogation centres – was the key element in Britain’s political and military offensive’

THE ASSASSINATION of activists involved in the anti-H- Block/Armagh campaign was a clear indication that Britain’s criminalisation policy and its importance to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s attempts to destroy republicanism was being undermined by the mass mobilisations in support of the prisoners.

The unionist Ulster Defence Association, associated most with the British policy of collusion, was responsible for the killings of John Turnly (a member of the Irish Independence Party) and Miriam Daly (of the Irish Republican Socialist Party) in June 1980. They also killed IRSP members Ronnie Bunting and Noel Lyttle in October that year.

On 16 January 1981, in a high-profile attack one of the most prominent of the H-Block campaigners, Bernadette McAliskey, and her husband, Michael, suffered multiple gunshot wounds in their County Tyrone home and left for dead.

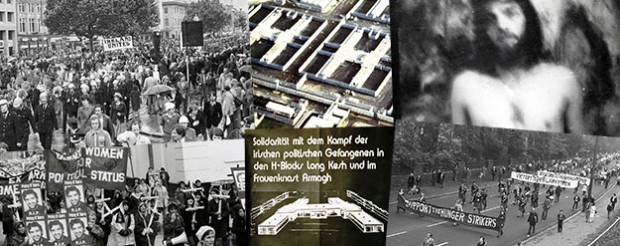

• H-Blocks/Armagh protesters march in County Tyrone: Miriam Daly (front left) and John Turnly (second row, with dark glasses) were assassinated by loyalists while Bernadette McAliskey (front, second from right) was shot and left for dead along with her husband

The gunmen were arrested on the spot by British paratroopers who were helicoptered into the area on 15 January and, it is believed, simultaneously had the McAliskey home under surveillance.

The suspicion at the time was that the British knew of the attack but were content to allow it to happen then arrest the assassins as some sort of propaganda coup.

Jim Gibney has no doubt the British directed this campaign of assassinations, “But, like their use of thousands of plastic bullets aimed at suppressing the resistance and defiance of our communities, it didn’t work.

“To paraphrase Bik McFarlane’s tribute to Bobby Sands in Song for Marcella ‘We’re stronger now, you showed us how freedom’s fight can be won’.”

• • •

• Jim Gibney

“THE BRAVERY of the people on the streets matched that of the prisoners in the H-Blocks during the Hunger Strike year of 1981,” Jim Gibney told An Phoblacht’s Peadar Whelan on Thursday 20 August, the 34th anniversary of Michael Devine’s death and just days before the annual Hunger Strike Commemoration in Dundalk, County Louth.

An INLA Volunteer, Devine – or “Red Micky” – was the last of 10 republican prisoners to die during that epic year of 1981 in a prison struggle that marked a turning point in the struggle in Ireland and defined the direction republicanism would take in the next decade.

“The British Army and RUC fired over 30,000 plastic bullets during 1981, with a substantial number fired in May when Bobby, Francie, Raymond and Patsy died,” he said, referring to Bobby Sands, Francis Hughes, Raymond (McCreesh) and Patsy O’Hara.

“Seven people were killed as well as hundreds badly wounded. Yet the people kept coming on to the streets in support of the prisoners.”

To emphasise his point, Gibney recalled how people attending protests and pickets protected their children with cycling helmets.

“But despite their fear, and the real danger they faced, the people stayed on the streets.”

An Phoblacht was interviewing Gibney, one of the key republican activists at the heart of the struggle for political status, about his role in the National H-Block/Armagh Committee and the dynamic of a campaign that grew from being the proverbial acorn that became the mighty oak that Britain’s criminalisation policy couldn’t deal with..

“One of the ironies of how things evolved in that mid-1970s period was that people like Fergus O’Hare and John McNulty of People’s Democracy were handing out leaflets at Clonard Monastery warning about the threat of ‘political status’ being removed.”

Gibney maintained that republicans were trying to get to grips with the politically confusing situation created by the 1974/75 “ceasefire” and also the ending of internment, which many interpreted as a positive move by the then British Labour Government.

In his book Gangsters or Guerrillas? Representations of Irish Republicans in ‘Troubles’ Fiction, former POW Patrick Magee (convicted of the 1984 IRA bomb attack on Margaret Thatcher and the Tory Party conference in Brighton) saw things differently.

“To those of us in Long Kesh who witnessed the construction of the H-Blocks at the very same time as internees were being released, it seemed that Britain had merely changed tack.

“To republicans, every British political initiative had its hidden military agenda. The British state embarked on a policy designed to politically isolate Irish republicanism.”

Criminalisation – linked in a three-pronged strategy with ‘normalisation’ and ‘Ulsterisation’ and built on the torture of republicans in the various RUC interrogation centres – was the key element in Britain’s political and military offensive.

“In reality,” Jim Gibney said, “at the end of 1975, we didn’t know what we were facing. It was an unreal situation.”

• As more prisoners were sentenced, Relatives Action Committees were created in many areas

Trouble erupted

In 1976, the new prison regime saw the end of segregation in Belfast’s remand prison, Crumlin Road.

Trouble erupted as republicans and loyalists fought to be separated.

It was against this background, according to Gibney, that a public meeting was held in the Ballymurphy Tenants’ Association premises on the Whiterock Road with local women Maura McCrory and Lily Fitzsimmons (whose sons would end up on the Blanket Protest), Mary McDermott (whose Seán was killed on active service in 1976), Fergus O’Hare of People’s Democracy, and Miriam Daly (see info box) to the fore.

“This was basically the meeting of the Relatives Action Committee (RAC) which would, as time went on and more and more prisoners were sentenced, be replicated throughout the country.”

Another indication of the confusion republicans faced was when Lower Falls man Kieran Nugent was sentenced in September 1976 to become the first republican to challenge the new criminal regime in the newly-built H-Blocks.

Gibney told how Tom Hartley, based in Sinn Féin’s old headquarters at 174 Falls Road, recounted how Nugent’s family arrived at the offices in a stressed-out state because they couldn’t find out where Nugent had been brought after his conviction.

“It took two weeks for us to locate him,” Gibney remembers.

Nugent had been transferred to the H-Blocks where he refused to wear the prison uniform or carry out menial prison work.”

Stripped naked, he donned a blanket and so began a prison struggle that would send out shockwaves that would shake the political establishments throughout Ireland and Britain.

In a twist of fate, Jim Gibney would spend most of the next year on remand in Crumlin Road Prison. It was while in prison then that Gibney gained a sense of the significance of what was happening in the prisons and an insight that many republicans at this early stage of the protest didn’t grasp.

“The military struggle was all-encompassing and the Movement saw the prison issue as a side issue,” Jim Gibney admitted. “You could argue that the British Government had made the prison issue and criminalisation a central plank of their strategy and initially republicans didn’t catch on.”

As more and more prisoners were sentenced and “went on the Blanket” in protest against wearing prison uniform, the more their families, mostly the mothers, banded together to form local committees. These would soon amalgamate into a broad front under the umbrella of the Relatives Action Committee and took to the streets to highlight the plight of the prisoners.

“Women like Maura McCrory and Lily Fitzsimmons from Belfast as well as Mary Nelis and Kathleen Gallagher in Derry were incredible. They had enormous energy and courage and were not afraid to take their protests anywhere they could to expose the brutality of the regime.

“Bernadette McAliskey was formidable when she brought her energy to the campaign.

“In reality, the relatives dragged republicans along.”

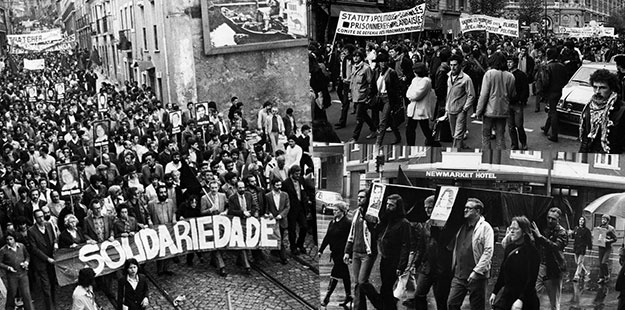

• Support for the political prisoners and their demands came from all across Ireland in mass rallies

Relatives Action Committees

After Bloody Sunday in Derry, which a lot of people see as the death of the civil rights movement, street politics all but disappeared, Jim Gibney suggested.

“What the RACs did was to mobilise people and bring people back onto the streets in what was, effectively, a challenge to the authority of the state over the treatment of the prisoners in both Armagh Women’s Prison and Long Kesh.

“The women symbolised what needed to be done as they marched and protested wearing blankets. Their determination saw the revival of street protest.

“As the protest in the H-Blocks escalated into the “No-Wash Protest”, forced upon the prisoners by the regime’s reaction, conflict became more intense.

“The incidents of physical and mental abuse were increasing as the British, the NIO and prison authorities tried to break the protesters. And the more reports of ill-treatment and abuse that emerged, the more the street protests intensified.”

As the prison protest dragged on and a stalemate ensued, the debate turned to the next challenge.

Jim Gibney (at this point a key link between the prisoners, the RAC and Sinn Féin) recounted how the Guardian newspaper’s David Beresford asked him in an interview what political status would mean in practice.

“I couldn’t answer him,” Gibney confessed.

As debates took place around the direction of the campaign and the actual meaning of political status, what emerged was the formation of the National H-Block Armagh Committee, formed in 1979, and “The 5 Demands” which were the nuts and bolts of political status.

• Rallies in support of the prisoners took place across the globe

All-Ireland campaign

The broad-based committee included people from both north and south of the Border and set out to raise awareness of the prison protest across the whole country.

“Quite simply we needed to broaden support for the prisoners, put pressure on the Dublin government and mobilise around the five demands.”

With the beginning of a first hunger strike in 1980 by seven H-Block prisoners who were joined by three Armagh POWs, the street campaign became more urgent and mass rallies took place throughout the country, indicating that people weren’t prepared to stand by and allow prisoners to die.

The confusing end to the first hunger strike was a demoralising blow that the British interpreted as a defeat for the prisoners and their supporters and encouraged their intransigence.

“By refusing to negotiate a settlement, the British created the conditions for the second hunger strike,” said Gibney.

During that second hunger strike, Jim Gibney said:

“Bobby’s election as a Westminster MP was the catalyst for profound political change across the country.

“Bobby was elected on 9 April. Two days later, at the Fianna Fáil Ard Fheis, Taoiseach Charlie Haughey, in his Presidential Address, did not even mention the H-Blocks or the hunger strikes yet in the general election of June that year Hunger Striker Kieran Doherty in Cavan/Monaghan and Blanketman Paddy Agnew in Louth won Dáil seats and brought down the Haughey Government.

“Fianna Fáil has never been in power on its own since and look where it is now – looking over its shoulder at Sinn Féin.”

Wrapping up our look back at that time, Jim said:

“That period was one of those moments in history when the people stretched themselves both inside and outside the prisons.

“Sinn Féin emerged as the party that could and would deliver for the people of Ireland. Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness have emerged as the most formidable leaders of Irish republicanism since Collins and De Valera and they have brought us to the point where a united Ireland is achievable, despite what our political enemies say.”