2 November 2014 Edition

The Brighton Bomb – 30th anniversary

History, memory and political theatre

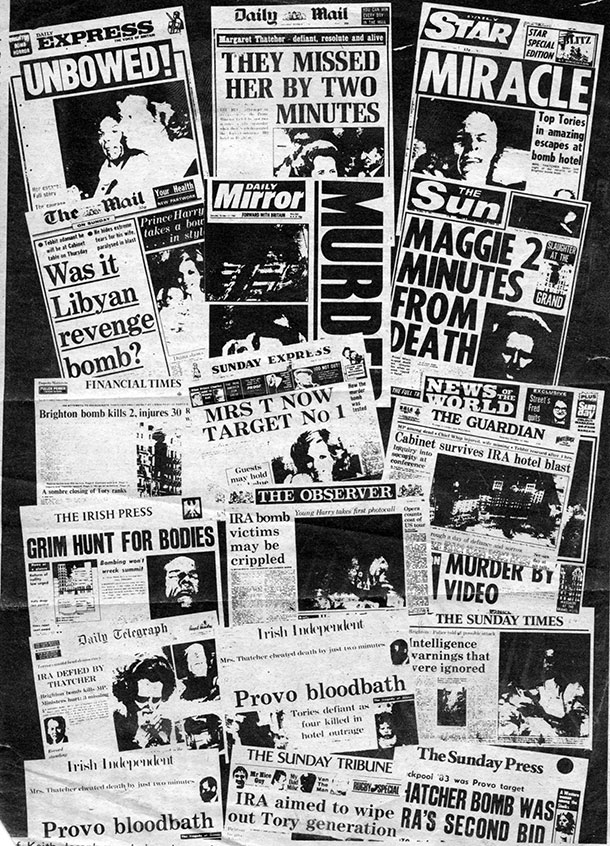

• Media reactions to the Brighton bombing

The events aimed to explore ‘the rarely discussed legacies of the Irish conflict in Britain’

Brighton University symposium to mark 30th anniversary of IRA attack on Margaret Thatcher’s Government, 12 October 1984

“THERE IS ONLY very patchy evidence that the British public and political opinion has been willing to engage in critical self-reflection of ‘The Troubles’ and in particular the role of the British state in the conflict . . . in sharp contrast to the position in Northern Ireland itself, where efforts to discuss the contested past have been a fundamental aspect of the contemporary political discourse.”

This by Stephen Hopkins (Leicester University) at the two-day symposium held in Brighton on 15/16 October to mark the 30th anniversary of the IRA bombing of the Grand Hotel during the 1984 Conservative Party conference was timely when the Peace Process is in danger of foundering due to unionist obduracy fostered by a disengaged and neglectful British Government.

Symposium organiser Brighton University Professor Graham Dawson leads a research group on ‘Understanding Conflict: Forms and Legacies of Violence’. He said the two-day series of events aimed to explore and hopefully challenge “the rarely discussed legacies of the Irish conflict in Britain”, breaching some of the silences and taboos in public and political discourse both during and after the conflict: “What can’t be spoken of.”

The problem was illustrated by responses to other commemorative events held that week in Brighton and London, including an event for young people ‘What’s the Alternative? Beyond Violence, Injustice and Extremism’, and a screening of the film Beyond Right and Wrong, followed by a discussion about the Brighton Bombing.

A public conversation between Jo Berry, daughter of the late MP Anthony Berry, killed in the Grand Hotel, and Patrick Magee, the IRA Volunteer convicted of the bombing, met with a hostile reaction on social media and in the local press, demanding that Magee apologise and “name names”. The spirit of listening and empathy was distinctly missing. Instead, the old demonising of the IRA and the “closing down of space for alternative voices” (Professor Dawson’s words) that characterised ‘The Troubles’ in Britain emerged again.

The symposium opened with presentations from academics, researchers and former activists on legacies and impacts of IRA campaigns in Britain. Queen’s University’s Gary McGladdery asked whether the bombing campaign in Britain advanced the republican political agenda or set it back. Lesley Lelourc (Rennes University) described how the Warrington bomb was a catalyst for reconciliation. Nadine Finch (human rights lawyer and former Labour Party activist in the 1980s) tracked the impact on security and rights: strip searching, prisoner abuse and plastic bullets, the Prevention of Terrorism Act, the broadcasting ban, harassment of Irish people at ports, the prevalence of anti-Irish racism, and the arduous task of getting the experience and politics of republicans heard inside the Labour Party.

• The aftermath of the IRA’s attack targeting the British Cabinet at the Grand Hotel

In his hard-hitting paper Stephen Hopkins said that “the UK state’s tendency to deny its role and activities as a protagonist in the conflict” makes truth recovery in the North of Ireland and within Britain harder to achieve. He criticised the post-Blair establishment for their misleading claims for the Peace Process as a “model of conflict resolution” by a government with neutral status. Although much grassroots healing and reconciliation work is happening (such as the Pat Magee and Jo Berry engagement and Jo’s ‘Building Bridges for Peace’ NGO), this is “despite the ambiguity and neglect at the heart of Britain’s response”, he said.

The centrepiece of the symposium was the reading of a draft play by two Brighton writers, Josie Melia and Julie Everton. The play is based on interviews with Jo Berry and Patrick Magee, and other people who experienced the Brighton bomb: hotel staff, other guests, emergency services, journalists, members of the local Irish community, historians and politicians. It skilfully weaves a narrative about the experiences of the bombing itself by a group of fictional characters, with the story of the real-life reconciliation between Jo Berry and Pat Magee.

In the post-play discussion of political theatre (with local writers, Belfast’s Paula McFetridge of Kabosh, and David Wybrow, director of London’s Cockpit Theatre), Melia and Everton acknowledged that the role of British state violence and responsibility was not part of their play. They said disarmingly they have not yet figured out a way to dramatise this yet, but will tackle it by the time the play is finished next year. To be fair, it is touched on through some quiet comments the Magee figure makes about the context of the attack being “an act of war, not personal”.

As a former Sinn Féin activist in London at the time of the Brighton bomb, I found this symposium to be a praiseworthy initiative, opening up discussion of the aftermath of the conflict in Britain to a plurality of hitherto silenced voices. Hopefully it is just the beginning.