2 November 2014 Edition

The HET – Historical failure to deal with state’s past

PSNI Historical Enquiries Team to be scrapped and replaced with a new investigations unit

• HET investigations into killings by the British Army were shelved

THE NEWS at the very end of September that the largely discredited Historical Enquiries Team (HET) is to be jettisoned by the PSNI due to budget cuts may be of little concern to some (if not many) nationalists but cuts to the Police Ombudsman’s Office is a different case altogether.

Set up in 2005 by former PSNI Chief Constable Hugh Orde to investigate the deaths of more than 3,000 people between 1968 and 1998, the HET came under the direct control of the PSNI’s Intelligence Branch and therefore lacked the independence required to investigate conflict-related killings.

This point was driven home in July of last year when HET investigations into killings carried out by the British Army were shelved.

The move came after the HM Inspectorate of Constabulary police watchdog reported that the HET investigated state killings with “less vigour” than those carried out by non-state forces.

As a consequence, inquiries into killings carried out by British soldiers were shelved and HET Director Dave Cox resigned.

PSNI Temporary Deputy Chief Constable Alistair Finlay said the force will form a smaller Legacy Investigations Branch to replace the HET, which will be wound up by Christmas.

Also in the cuts firing line is the Police Ombudsman’s Office, which is to lose 8% of its budget. A number of major inquiries due to be undertaken by the Ombudsman will now be postponed. These involve the killings of dozens of nationalists by the notorious South Armagh-based ‘Glenanne Gang’ (made up of serving and ex-members of state forces and unionist paramilitaries) and an investigation into the 1975 Kingsmills killings (claimed by the ‘South Armagh Republican Action Force’) will also be affected.

While the loss of the HET will not cause nationalists too much concern, they might see the Police Ombudsman’s office differently.

The present Ombudsman, Dr Michael Maguire, has done much to restore the credibility of the office after the disastrous tenure of Al Hutchinson.

Maguire’s widely-reported threat to take the PSNI to court in June of this year over its refusal to hand over files in respect of 60 killings (including the UVF attack on The Heights bar in Loughinisland, County Down, in June 1994 during an Ireland World Cup soccer match) was a sign of his willingness to fulfil his role without fear or favour.

The situation was resolved when, in early September the new PSNI Chief Constable, George Hamilton, agreed to give Maguire access to the relevant files.

With the Ombudsman’s powers to properly investigate the state’s role curtailed, those on the British side responsible for the killing of citizens – directly or indirectly through collusion with unionist death squads – will most likely breathe easy again as accountability is once more postponed.

Had Maguire’s earlier legal bid gone to a full hearing, it would likely have exposed a legal structure that has protected the RUC, British Army and subsequently PSNI officers from prosecution for the past 45 years.

Reacting to the findings of the 1970 inquiry by London Metropolitan Police Chief Superintendent Kenneth Drury into the death of Sammy Devenny (beaten by the RUC in his Bogside home in April 1969 and dying later of his injuries), the then RUC Chief Constable, Sir Arthur Young, announced that he could not identify those responsible because of what he described as “a conspiracy of silence” among his own police officers.

That “conspiracy of silence” has persisted down the decades and right up to today. And the Drury report has recently been reclassified by the British Government and will remain secret until 2022 – at least.

• Sammy Devenny was killed by the RUC

Counter-insurgency

As the political crisis in the North worsened through the late 1960s and into the early 1970s, the British authorities, despite public claims that they were dealing with a ‘law and order’ situation, were privately tailoring strategies developed during their recent experiences in fighting anti-colonial and counter-insurgency wars in Africa and the Far East to (once again) suppress republicanism in Ireland.

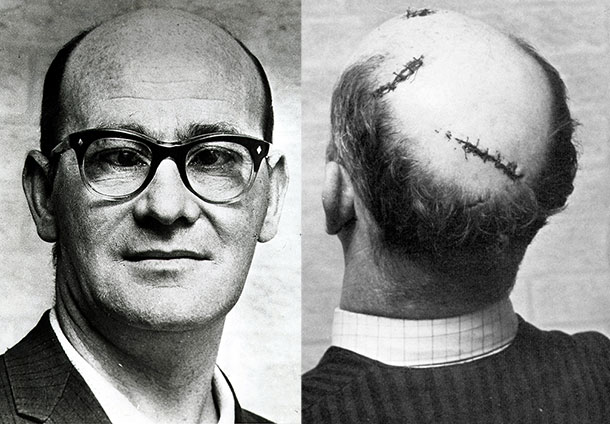

Brigadier Frank Kitson, a senior British Army counter-insurgency theorist whose strategies were outlined in his book Low Intensity Operations, smoothed out the contradiction that allowed the ‘law makers to become law breakers’ when he wrote:

“No country which relies on the law of the land to regulate the lives of its citizens can afford to see that law flouted by its own government, even in an insurgency situation. In other words, everything done by a government and its agents in combating insurgency must be legal. But this does not mean that the government must work within exactly the same set of laws during an insurgency as existed beforehand, because it is a function of government to make new laws when necessary.”

• Brigadier Frank Kitson

Brigadier Kitson (who was to rise through the high command of the British Army and be knighted by the British queen to become General Sir Frank Kitson GBE, KCB, MC & Bar DL, “Commander-in-Chief, UK Land Forces”) added:

“Anyone who is prepared to use illegal force against his own country [sic] has no right to expect anything other than total extermination, as fast as possible, by any ‘legal’ means.”

Kitson’s paradigm was constructed to make ‘law and order’ mean what the British wanted it to mean.

An example of this is the arrangement that become known as the “Tea and Sandwiches Agreement”.

This 1970 arrangement – involving the Chief Constable of the RUC, the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the British Army as well as the judiciary – ensured that no British soldier involved a shooting, fatal or otherwise, would be investigated by the civil authority. This effectively gave them immunity – a licence to kill.

Between 1970 and 1973, British soldiers shot dead more than 150 people in the North. Not one was ever prosecuted.

State’s ‘shoot to kill’ policy

Kitson also advocated the use of what he called ‘counter-gangs’ – undercover military units operating on their own or with locally-recruited death squads.

The spotlight was recently shone on the activities of one such British Army unit, the Military Reaction Force (MRF).

In November 2013, members of the MRF admitted on a BBC Panorama programme that they shot and killed unarmed civilians.

Despite their on-camera boasts that they were “not there to act like an army unit” but there “to act like a terror group”, the PSNI announced in May 2014 that none of the MRF soldiers had “admitted a criminal act” and no action would be taken.

The crude methods of the 1970s would be replaced in the 1980s with a more sophisticated ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy.

In north Armagh in 1982, six unarmed men were shot dead by a specialist RUC unit, E4a. This police unit was trained by the SAS.

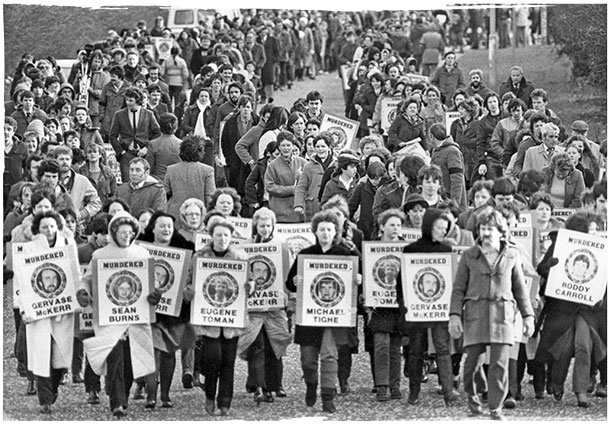

Three of the dead were IRA Volunteers: Eugene Toman, Seán Burns and Gervaise McKerr; two, Roddy Carroll and Seamus Grew, were INLA members; 17-year-old Michael Tighe was a civilian.

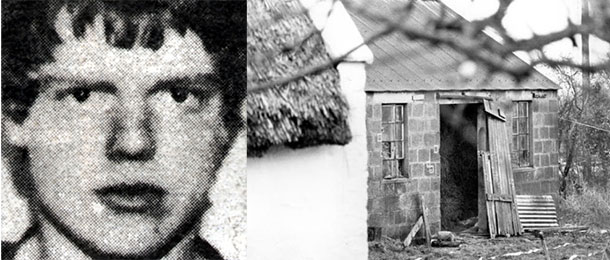

• Teenager Michael Tighe was murdered by British soldiers staking-out a hayshed

Martin McCauley was shot and seriously injured in the same incident in which Tighe was killed. The RUC said both men were armed and they issued a warning before opening fire. McCauley rejected this, saying the police opened fire, unleashing 47 rounds without warning, and the two targets had not fired at the RUC. It transpired that the hayshed where the shooting occurred was under MI5 surveillance and that tape recordings of the incident, which would have supported McCauley’s version of events were destroyed.

McCauley was convicted of possessing rifles found in the shed, a conviction that was overturned in Belfast’s Court of Appeal in May 2014 as it was found to be unsafe.

In respect of the other killings, four RUC members were charged but eventually acquitted by a non-jury Diplock court’s judges whose ruling underpinned the rationale behind the shoot-to-kill policy.

Judge McDermott, contrary to forensic evidence presented at RUC officer John Robinson’s trial, said he accepted Robinson’s claim that he had been fired on.

McDermott also ruled that he was “not conducting an inquiry into how the officers acted . . . I am not concerned with any RUC cover-up”.

It was the acquittal of RUC officers Sergeant William Montgomery and Constables David Brannigan and Frederick Robinson of killing Eugene Toman in the first shoot-to-kill ambush that sent the clear message from the judiciary that it was legal to kill suspected republicans.

When freeing the three RUC men, Lord Justice Maurice Gibson commended them for their “courage and determination in bringing the three deceased man to justice — in this case, to the final court of justice”.

Relatives for Justice

According to Relatives for Justice, an advocacy group representing the families of people killed by state forces, of the almost 400 people killed by the state, over half were unarmed civilians and 75 were children.

Only four British soldiers have been convicted of killing civilians in the North:

Light Infantry soldier Ian Thain served 22 months for the 1983 killing of Thomas ‘Kidso’ Reilly;

Paratrooper Lee Clegg served just over two years for shooting dead Karen Reilly (no relation to Thomas Reilly) in 1990;

Scots Guardsmen Mark Wright and James Fisher served six years after being found guilty of gunning down Peter McBride in north Belfast in 1992.

The British Army continued to pay the wages of all four while in prison and they were welcomed back into their regiments on their release.

The actions of the locally-recruited Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), formed in 1970 to replace the notoriously sectarian B-Specials paramilitary police, provided another example of how breaking the law — according to the Kitson dictum — was legal if it served British political interests.

A 1973 British Government document, uncovered in 2004, titled ‘Subversion in the UDR’, found that between 5% and 15% of UDR soldiers in 1972 were members of unionist paramilitary death squads, primarily the UVF and the UDA.

The report said that the UDR was the main source of weapons for unionist paramilitaries at the time and revealed that 70 members of two UDR companies based in Girdwood Barracks in Belfast had links to the UVF and that UVF members socialised with UDR soldiers in their British Army ‘mess’ on base.

As the notorious Glenanne gang was made up of members of the British Army’s largest regiment, the UDR, and the RUC as well as the UVF, it may not be a coincidence that the Ombudsman’s investigation into its activities is now stalled as the political clash over welfare cuts ordered by the Tory-led British Government at Westminster rumbles on.