1 October 2014 Edition

Thomas Davis – 200th anniversary of his birth

Remembering the Past

• Thomas Davis

A nationality which may embrace Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter – Milesian and Cromwellian – the Irishman of a hundred generations, and the stranger who is within our gates

THOMAS DAVIS was one of the most significant Irish nationalists of the 19th century. His writings helped to shape Irish nationalism itself and they exercised a key influence on the cultural and political revival of the early 20th century.

Born in Mallow, County Cork, in 1814, Davis’s family background was Church of Ireland Protestant and his father was a surgeon in the British Army. When Davis was four years old, his father died and the family moved to Baggot Street, Dublin. It was there that he lived the remaining 23 years of his life. Educated in Morgan’s School, Davis said later he “learned to know, and knowing, to love my countrymen”. He also spent much time with relatives in Tipperary, a county that inspired his songs and informed his political views.

Davis began as a supporter of the British Liberal Party but in Trinity College, where he studied arts and law, his Irish nationalism developed. He entered Trinity in 1831 on the same day as a young Presbyterian from Newry, John Mitchel, who was also to become a hugely influential Irish nationalist.

In 1840, Davis gave an address to the Trinity College Historical Society in which he urged the privileged, English-oriented students of what was then the only university in Ireland to study the history and literature of Ireland. His point was summed up in his phrase “Gentlemen, you have a country.” While this fell on many deaf ears it was heard by some who would go on to play leading roles in the Young Ireland movement.

In 1841, Davis joined the Repeal Association led by Daniel O’Connell, campaigning for Repeal of the Union with Britain and legislative independence for Ireland. While he recognised O’Connell as the leader of the Irish people, Davis sought a deeper form of national revival, cultural and economic as well as political. Two other like-minded journalists were John Blake Dillon and Charles Gavan Duffy.

• John Blake Dillon and Charles Gavan Duffy

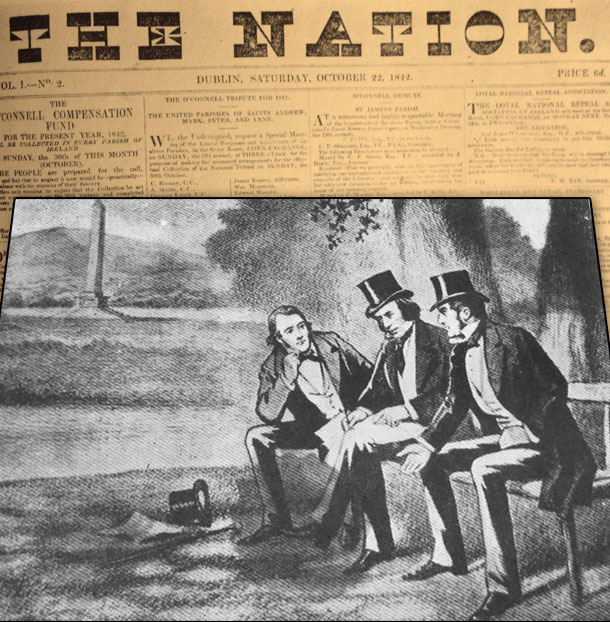

In the spring of 1842, Davis, Dillon and Duffy agreed to establish a weekly paper to champion the nationalist cause. They made their decision after a walk in the Phoenix Park, described by Duffy: “Sitting under a noble elm in the park, facing Kilmainham, we debated the project, and agreed on the general plan.”

The first issue of The Nation newspaper appeared on 15 October 1842. Twelve thousand copies were sold on the first day. Sales increased in the months ahead as the paper became the main organ of the Repeal movement and its rousing prose and verse stirred nationalist feeling throughout Ireland.

Davis set out the non-sectarian basis of the The Nation in its “Prospectus”:

“A nationality which may embrace Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter – Milesian and Cromwellian – the Irishman of a hundred generations, and the stranger who is within our gates. Not a nationality which would prelude civil war but which would establish internal union and external independence; a nationality which would be recognised by the world, and sanctified by wisdom, virtue and prudence.”

John Mitchel later (in The Last Conquest of Ireland) credited Davis with winning much Protestant support for the cause:

“Whatever was done, throughout the whole movement, to win Protestant support, was the work of Davis. His genius, his perfect unselfishness, his accomplishments, his cordial manner, his high and chivalrous character, and the dash and impetus of his writings, soon brought around him a gifted circle of young Irishmen of all religions and none, who afterwards received the nickname ‘Young Ireland’.”

• Thomas Davis, Charles Gavan Duffy and John Blake Dillon discuss founding 'The Nation' newspaper under a tree in the Phoenix Park, Dublin

While Davis and Young Ireland supported O’Connell they were independent of him. They were suspicious of his relationship with the British political parties, his focus on Westminster and his overblown rhetoric. When O’Connell proposed the convening of a ‘Council of 300’ to act as a kind of Irish parliament, along the lines followed later by Sinn Féin, the Young Irelanders enthusiastically supported the call but were bitterly disappointed when O’Connell backed down. This was even more the case in 1843 when ‘The Liberator’ caved in and cancelled what was to be the largest of his ‘monster meetings’ at Clontarf after the British Government banned it.

Through all this period Davis wrote prolifically for The Nation. He urged the development of all aspects of Irish life and a spirit of self-reliance which, again, prefigured Sinn Féin. Unlike O’Connell, who urged the Irish people to drop the Irish language, Davis championed it:

“To impose another language on such a people is to send their history adrift among the accidents of translation – ’tis to tear their identity from all places . . . A people without a language of its own is only half a nation. A nation should guard its language more than its territories – ’tis a surer barrier, and more important frontier, than fortress or river . . . To lose your native tongue, and to learn that of an alien, is the worst badge of conquest – it is the chain on the soul.”

Davis was acutely aware of the economic ruin that resulted from the conquest of Ireland by England and the mass poverty caused by the rack-renting landlord system. He pointed to the Scandinavian system of ownership of land by the people in their own farms and called for the abolition of landlordism:

“Those whom the people trust must cease to trifle with romantic schemes, and apply themselves, body and spirit, to the work of emancipating the peasantry. While the people remain feudal serfs they will be trampled beggars. Free the peasantry from the aristocracy. All else is vanity and vexation of spirit.”

Davis did not live to the see the most catastrophic result of the landlordism he condemned – the Great Hunger which struck Ireland within months of his death. He died on 15 September 1845, just before his 31st birthday. The best remembered of his writings are his songs such as A Nation Once Again, The West’s Asleep and Tone’s Grave (In Bodenstown Churchyard). However, all his writings deserve to be remembered.

• Thomas Davis was born on 14 October 1814, 200 years ago this month.