2 March 2014 Edition

At Swim, Two Salmon

• Damaged Gerahies salmon cages: 'Not much of a barrier left there,' says Tony Lowes

Salmon farms along the west coast of Ireland do not get the same protection as those in Norway and Scotland, where the fjords and lochs give shelter from the storms.

26 DECEMBER 1796: Wolfe Tone laments his fate.

“Notwithstanding all our blunders, it is the dreadful stormy weather and the easterly winds, which have been blowing furiously and without intermission since we made Bantry Bay, that have ruined us.”

Five days have passed since the winds caused a collision between La Resolu and Redoutable, and La Resolu’s longboat was swept ashore on Bere Island. The Surveilant is badly damaged, later scuttled.

“Two o’clock,” Tone writes in his diary on the 22nd, “we have been tacking over since eight this morning, and I am sure we have not gained one hundred yards; the wind is right ahead, and the fleet dispersed, several being far to leeward.”

By the 29th, after nine days of raging seas and snowstorms, Tone is distraught. “The elements fight against us, and courage is of no avail.”

The attempt fails, the colonial grip is tightened, the status quo is unaltered, the Beara peninsula is changed forever. All that remains is the memory of the inclement weather that wrecked the hopes of the liberators.

And La Resolu’s 12-metre longboat — submerged in Berehaven harbour for 102 years until it was moved to Bantry House in 1898, then to the National Museum in 1944.

This was a ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore double-mast vessel. Built with assorted hardwood, it was capable of good speed under sail and good movement under oars, crewed by 13.

• Bad weather at Bantry Bay foiled French attempts to aid the United Irishmen in 1796

La Resolu sails again

Sunday morning, 9 February 2014, retired seafarer Alec O’Donovan takes a replica of the La Resolu longboat onto the bay with a young crew. The storm has abated and the teenagers, keen to experience a nostalgic thrill, won’t endure the fate of the La Resolu’s crew.

O’Donovan has mixed feelings about the storms.

“For 25 years there were very few serious storms, now they are back, storms once a fortnight since October. They come straight in from the Atlantic, from the south-east – raging sea, big swell. Anything out there is severely damaged, even during lulls.”

The 68-year-old is secretary of ‘Save Bantry Bay’, a group dedicated to the preservation of wild fish against the vagaries of the farmed fish industry.

His task is a mighty one. The forces ranged against him are strong but (unlike Wolfe Tone, the United Irishmen and the redoubtable French), he has the wind in his sails and the elements in his favour.

If one thing is likely to stop aquaculture it is the elemental force of nature.

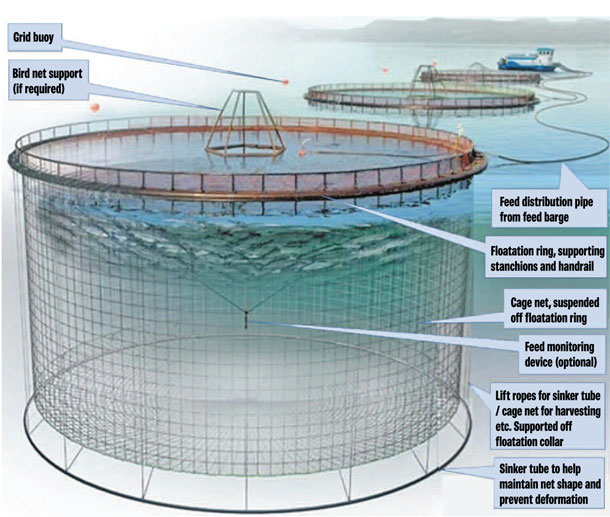

Salmon farms along the west coast of Ireland do not get the same protection as those in Norway and Scotland, where the fjords and lochs give shelter from the storms.

Location, therefore, is crucial in the aquaculture business.

• Retired seafarer Alec O’Donovan is the secretary of the ‘Save Bantry Bay’ campaign

Huge risk

Norwegian-owned Marine Harvest Ireland moved into Bantry Bay in 2009 when it took over John Power’s Silver King Seafoods salmon farm and immediately made plans for expansion.

Marine Harvest admits that Bantry Bay, which faces west-south-west into the prevailing wind of the Atlantic, offers little shelter from the most severe storms and winds.

Their proposed 2,800-tonne farm for Bantry Bay is adjacent to Shot Head, close to Adrigole, between Glengariff and Castletownbere. Shot Head, say Marine Harvest, has adequate depth and is afforded some shelter by Bere Island.

Alec O’Donovan, others in the Bantry Bay group, fishers and sailors believe they are taking a huge risk with their choice of site.

“This is the most exposed part of the bay. There is no shelter. The chances of destruction are very high.”

Marine Harvest argues it has no choice.

“Going further east, whilst the bay offers progressively increasing shelter, areas with adequate depth become fewer. In addition, the needs of maritime traffic and existing users — including the Tarmac Fleming Quarry at Leahill, the Conoco Philips Bantry Bay Oil Terminal on Whiddy Island, the fishery harbours at Bantry and Glengarriff, and traditional inshore fishery operations, as well as mussel lines and a second salmon farm operator — leave no sufficiently large, vacant site options available.”

Simon Coveney (Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine) gave an obtuse reply in the Dáil on Tuesday 11 February when he was asked about the salmon cages belonging to Murphy’s Seafood of Gerahies, the second salmon farm operator in the bay.

“Damage has been done to one of the cages on site and . . . a fish loss is likely to have occurred as a result. Due to the ongoing weather conditions it has not been possible to quantify the fish loss but the company has advised that a fish count will be taken as soon as weather conditions permit.”

Tony Lowes, Friends of the Irish Environment (FOIE), says between 60,000 to 80,000 salmon weighing up to four kilos escaped along with young salmon, “probably tens of thousands . . . who will drift along the coast and then breed anywhere that comes up”.

Marine Harvest was also affected by the inclement weather, reporting financial losses for 2013 as a result of the “very challenging” Irish climatic conditions. Rising seawater temperatures caused the proliferation of parasites and diseases. Storms made it difficult to feed the fish and control sea lice.

In its environmental impact assessment, Marine Harvest offers its emergency strategy for mass fish escape. It does not impress Tony Lowes. “This is closing the barn door after the horses have gone.”

These guidelines do not appear to be general and were not applied in Bantry during the recent storms. Two weeks after the Bridget’s Day storm wrecked the Gerahies farm, Marine Minister Coveney was still waiting to hear the extent of the damages.

Lowes asks the obvious questions.

“What about the promise of immediate inspections by divers, and how many times have the fish even been fed to observe the sudden drop in feeding behaviour?”

This, he says, is a sign of the times.

“A changing climate will create challenging conditions for many traditional industries. Those that won’t adapt do so at their own peril, and sadly at a great cost to the environment.”

Minister Coveney, in the same 11 February reply, rejected any adverse effect on wild salmon. “There have been no documented cases in Ireland of negative population impacts leading specifically to loss of wild stock integrity and productivity.”

O’Donovan is dismayed by this comment.

“We have the unjust situation where the minister orders the expansion of salmon farming, repeatedly states that he is guided by the Marine Institute, whose independence has been called into question, ignores the advice of Inland Fisheries Ireland, the statutory body tasked with the protection of wild salmon and sea trout, appoints the members of a supposedly independent appeal board, and then makes the final decision.”

Coveney met with representatives of Marine Harvest in early February. Following the meeting, Marine Harvest indicated that a decision in its favour was imminent. O’Donovan was aghast.

“This from a minister who supposedly cannot get involved in the process.”

Vulnerable wild populations

The anti-aquaculture lobby also reminded the minister that the Marine Institute was responsible for a ten-year study on interactions between cultivated and wild salmon.

Published in October 2003, it provided “the first scientific evidence that interbreeding between wild and cultivated salmon . . . could lead to the extinction of vulnerable wild populations of Atlantic salmon”.

The Marine Institute said the study demonstrated “that where the number of farm escapees is high relative to the wild stocks, interbreeding has genetic and competitive impacts on wild salmon populations”.

The tit-for-tat posturing by the pro- and anti- aquaculture advocates has frustrated those who believe this is about two different social paradigms, the two types of salmon representing the oppositional views of the future of Irish society – one represents big corporate business, the other small rural communities.

The state has argued for many decades that these conflicts do not exist, that it is and has always been about jobs. Conservationist Damien O’Brien is not alone in believing it has also been about biodiversity, eco-systems and sustainability – subjects far from the minds of most people.

“I look around and see the apathy in this country. For the most part the people are either lambs or lemmings. Those that do care, not just about this issue but others, are fractured.

“This is endemic in the Irish psyche. When I first got involved in this I could see that we needed to formulate a structured approach to fight what even an idiot can see is wrong. However, it was evident that was too idealistic.”

Seafarer O’Donovan shares the view that the environmental concerns are being ignored because the corporates can sway the influence of communities and individuals with a baleful refrain.

“You are always going to have that conflict; it depends on who is going to win.

“Damage to the environment damages the country. This is pollution of the sea, pollution of the scenery and pollution of the body politic. It’s all about money.”

Bantry Bay has everything – fishing, fish farming, maritime, leisure, industrial and, when the sea is rough, the Spanish bring their trawlers in.

“There is only so much this bay can take,” says Breda O’Sullivan, who lives in Agrigole. The proposed farm will be at the end of her boreen. “This is why we are opposing it.”

“The oil and mussel industries had no impact on people making a living from the bay,” says Alec O’Donovan. “But this salmon farm is an entirely different thing. It has got a massive negative side-effect that should be looked at very carefully.”

Options

People who make their living from and on the sea oppose aquaculture off the west coast because it is, in simple language, a ‘stupid idea’. Others insist it is the wrong technology in the wrong place, and that land-based containment systems would be a better option.

Bord Iascaigh Mhara (BIM), the state agency responsible for developing the Irish seafood industry, argues that it is not technologically feasible to grow large volumes of fish on land, yet this year the Danes will begin harvesting 700 tonnes of salmon averaging a weight of four kilos from land farms. Plans for land fish farms in Abu Dhabi, Canada, China, Mongolia and the USA suggest this technology is feasible . . . and would work in Ireland.

Damien O’Brien believes land-based closed containment is inevitable.

“Sea-based salmon farming will destroy our environment and our wild stocks, and the livelihoods of those dependent on both.

“Land-based systems are not only environmentally friendly, offering safe and sustainable employment, they also produce a premium product. We have an ideal opportunity to be at the forefront of this industry but instead the elected representatives of this country are again choosing money and big business rather than looking at the best interests of the citizens of this state.”

Despite their courage, Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen did not prevail, but their legacy remains, especially in Bantry, where actions and events on the bay define the lives of everyone, even the blow-ins.