2 June 2013 Edition

‘Uncomfortable Conversations’ have begun

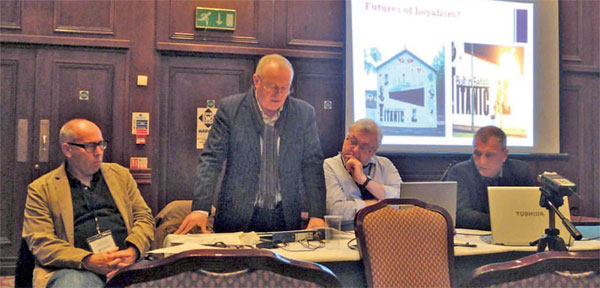

• Graham Spencer, Reverend Chris Hudson, Jim McAuley and former UDA prisoner Jackie McDonald at ‘The Future of Loyalism’ conference in April

Interestingly, the PUP document stresses reconciliation as a social rather than political process and does so because inclusivity, if it is genuine, must extend beyond the political

THE Progressive Unionist Party’s new document Transforming the Legacy (released on 22 April) is the first constructive response from unionism on the question of reconciliation. It is a response to Sinn Féin’s request for others to engage with the tortuous problems of how to deal with the past. Although constructed as a call to the loyalist base, it significantly touches one fundamental aspect of the reconciliation debate and any subsequent process: INCLUSIVITY.

Interestingly, the PUP document stresses reconciliation as a social rather than political process and does so because inclusivity, if it is genuine, must extend beyond the political. Politics is important to shape the climate for reconciliation and give official recognition to the structures and mechanisms that any reconciliation process will need. But the importance of inclusivity is that it offers the potential (if credible and with commendable conviction) to move outside of the restrictive boundaries and managed divisions that tie people to the past.

To envisage a future that is different and better it is clear that there must be a release from the divisive imaginations which have prevailed. The irony of all this, of course, is that insecurity feeds instability and in a zero-sum political society the pressure of gains means that progress is invariably measured by the scale of loss inflicted on others. In a ‘normal’ society such tensions are held within a frame of consensus politics, but in Northern Ireland such consensus is notably absent. Political progress for many depends on political regress for others; hardly a basis of reconciliation.

The starting point is surely the call for an honest and open debate about what kind of future the respective communities in Northern Ireland want and to consider how compatible or incompatible those perceptions of the future are. This would enable all to see to what extent each community constructs the idea of a future and where convergent and divergent interests are. All talk is about the past and none about the future. What kind of future might be imagined? Is it one where dominance or control comes to mind, or is it one where the desire for dominance and control are seen as a hindrance to that future?

Such questions reflect a need for what Sinn Féin’s Declan Kearney has called ‘Uncomfortable Conversations’. Those conversations also call for serious re-evaluation of what motivated and happened during conflict and looking beyond easy and immediate blame. This will be hard for those who inflicted pain and who absorbed it. One’s life can be formed by suffering and to move away from this fact must surely be the hardest journey of all. If reconciliation is anything it is the journey away from pain, but we must also be vigilant to the possibility that truth can make things worse as well as better; that when some hear what really happened in the death of their loved one they may feel compelled to seek justice or retribution in ways they would not have considered before.

The managing of truth, victims, justice and trauma in a reconciliation process will require very careful and sensitive handling. Each community views truth differently: one preferring to see truth in terms of individual responsibility, the other viewing it through the lens of social circumstances and context. This, it seems, is a good starting point in relation to the reconciliation debate and, in particular, to inclusivity.

What comes to mind for each community when they think of inclusivity?

Initially, it would perhaps be too much to expect common ground here but not too much to expect common interest and indeed, common value. If the core over-arching theme and concept of inclusivity can provide a foundation for the generation of common interest and value (and both republicans and loyalists are using the term inclusivity), it will provide a basis by which to proceed because it will have created the possibility of shared space in the debate.

For now, inclusivity must be necessarily ambiguous (just as the concept of ‘all’ is). It must have latitude that exceeds the conventions of political thinking. And this is where the PUP document has merit, because in conceiving reconciliation in terms of the social it marks a break from the traditions of the Protestant worldview where it is the individual that matters most.

In moving to the social, the PUP are actually emphasising a context which is of more appeal to Catholics than Protestants and this is ground-breaking. There will, of course, be much talk that resonates with the loyalist base but make no mistake – uncomfortable but necessary conversations have now begun and tentative but meaningful shifts are underway.

Graham Spencer is Reader in Politics, Conflict and the Media at the University of Portsmouth and has written widely on loyalism

Chris Hudson is a Unitarian minister at All-Souls in Belfast and has acted as a mediator between the UVF and the Dublin Government since 1993

Graham Spencer’s books include...

- The State of Loyalism in Northern Ireland

- Protestant Identity and Peace in Northern Ireland

- Ulster Loyalism After the Good Friday Agreement: History, Identity and Change

- Forgiving and Remembering in Northern Ireland: Approaches to Conflict Resolution