2 September 2012 Edition

Gerrymandering electoral boundaries

The Partition Act

• The abolition of proportional representation and gerrymandering meant unionists controlled 78 of the 80 councils

‘We must ultimately reduce and liquidate that [nationalist] majority. This county, I think it can be safely said, is a unionist county’ – Member of Parliament, later Crown Solicitor for County Fermanagh, EC Ferguson

MY FATHER, born in 1904, was a member of a Falls Road republican family. The family saw themselves as belonging to a national political majority. But my father’s status in belonging to this majority changed overnight, on 23 December 1920, as a result of the Government of Ireland Act.

Often referred to as ‘The Partition Act’, it was brought into force on 19 April 1921 and it allowed for the creation of two parliaments in Ireland. On 7 June 1921, the 40 unionist members of the new Northern parliament were sworn in; it was boycotted by its six Sinn Féin and six nationalist members. For unionists, there were two categories of people in their new state: the loyal, or unionist, and the disloyal, or nationalists. Simply put, a unionist emphasis on loyalty framed those with a different political view as disloyal. The effect of this unionist world view was to delegitimise opposition to partition. Avenues to address grievances were closed. Opposition to the state was seen as a threat, which was met with repressive measures and legislation. One of the most notorious pieces of legislation was the Special Powers Act. From that day to his death in 1978, my father, his family, and his community were trapped inside a state where they were categorised as disloyal and denied their political and economic rights.

In March 1914, British Prime Minister Asquith proposed an amendment to the third Home Rule Bill. This amendment allowed the counties of north-east Ulster to vote on whether they would remain within a Home Rule Ireland and so the amendment put partition on the agenda. That month, 58 officers of the British Army’s 3rd Cavalry Brigade, stationed in the Curragh Military Camp, told their superiors that if they were moved north they would prefer to accept dismissal. This act of mutiny reinforced the psychological underpinning of the unionist cause by the British ruling elite. On 24 April 1914, unionist opposition to Home Rule was strengthened by force of arms when Fred Crawford smuggled 25,000 rifles and two million rounds of ammunition into Larne Harbour (in fact, Fred had been smuggling guns into the North since 1910).

Of course, the rise and development of Northern unionism has a flipside: the violence inflicted on the Northern Catholic population, in particular the Catholic population of Belfast.

An examination of the years 1886, 1893, 1912 and 1920 reveals a pattern of violence by the unionist industrial working class in the Belfast shipyards. On 4 June 1886, 150 Catholic labourers employed in the building of the Alexandra dry dock were driven from the shipyard. On 22 April 1893, 600 Catholic workers were driven out of the yard. 1912 saw the expulsions of 3,000 Catholic workmen from the shipyards and other industrial sites across Belfast. It is also worth noting that many Protestant Labour Party supporters were expelled from their workplace during that year.

It was estimated by a Catholic welfare organisation, the Catholic Protection Committee, that on 20 July 1920, 10,000 Catholic men and 1,000 women were expelled from shipyards and other factory sites in Belfast.

The practice of expulsions of Catholics from their workplace was a forerunner of the structural discrimination of Catholic workers practised in the workplace in the Northern state.

On 8 September 1920, the British Government announced the creation of the Ulster Special Constabulary police force (the A, B and C Specials), many of whom were recruited from within the ranks of the Ulster Volunteer Force. By November of that year, the Specials were operational. This trend in recruiting from the UVF was exposed on 9 November 1921 when a proposal by an RIC Divisional Commissioner to assimilate the UVF into British state forces in the North was leaked to the press.

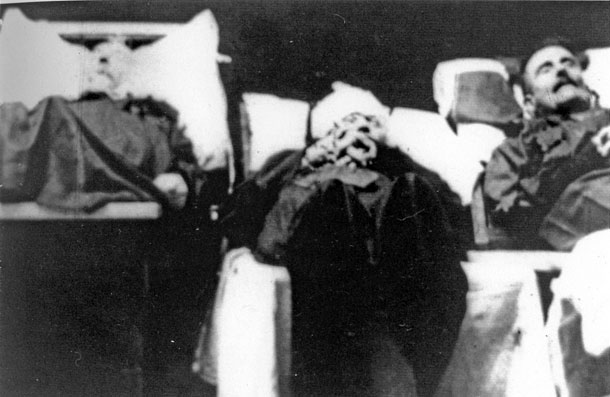

• The bodies of some of the civilians killed by the RIC in Belfast in the 1920s

Between July 1920 and July 1922, 257 Catholics were killed in Belfast, 11,000 put out of their jobs, and 23,000 driven from their homes. Many thousands fled south and over a thousand fled to Glasgow. Over 500 Catholic-owned businesses were burned and looted.

After 7 June 1921, the new Northern state quickly consolidated its hold on the Six Counties. The violence of that state was the cornerstone of unionist rule.

The Special Powers Act, internment and flogging, supported by a paramilitary police force with a unionist militia (the A, B and C Specials), were the foundations of the Northern state.

In early 1922, a new paramilitary commando group of 7,500 men was formed: the C1 Specials.

On 15 March of the same year, Dawson Bates, the Northern Minister of Home Affairs, introduced the Special Powers Act.

On 4 April 1922, the RUC, made up of 2,000 ex-Royal Irish Constabulary men and 1,000 A Specials, replaced the RIC.

On 22 May 1922, Stormont Prime Minister Craig introduced internment.

By mid-1922, there were 16 battalions of military, 5,500 A Specials, 19,000 B Specials, an unknown number of C Specials and 7,500 C1 Specials operating throughout the Six Counties. All of them were armed and paid for by the British Government.

Alongside the use of repressive measures, unionists began to reshape electoral boundaries.

Their first move in this direction took place in April 1922, when many nationalist councils were stood down and replaced by commissioners. This was quickly followed in July 1922 with a Bill to abolish PR in local elections. This Bill, passed in October 1922, empowered the Minister of Home Affairs to redraw electoral boundaries. Where nationalist majorities existed in urban and rural councils, the altering of electoral boundaries led to the sudden emergence of unionist-dominated councils. In the 1924 local government elections, nationalists controlled only two out of 80 councils.

From 1922 until the collapse of Stormont, unionist domination of the nationalist community had four main interlocking elements:-

- Special Powers Act, which enabled suppression of political opposition to Northern Unionism;

- Gerrymandering of political boundaries to maintain permanent unionist electoral majorities;

- Widespread practices of direct and indirect discrimination against nationalists in the workplace;

- Discrimination against nationalists in the allocation of housing.

Repressive legislation and a unionist judiciary was the enabling mechanism of state repression. The denial of political rights restricted the ability of the Northern Catholic population to highlight a political system that trampled all over their rights. Discrimination in the workplace imposed a barrier to economic opportunity and well-being. Discrimination in housing compounded the effects of poverty. All of these measures were meant to produce a sense of powerlessness in the Northern Catholic population.

In fact, the imprint of these four interlocking elements was embedded to such an extent in the unionist political psyche that they were openly endorsed by the unionist leadership. On 12 July 1933, Minister of Agriculture Sir Basil Brooke, in an infamous speech at Newtownbutler, referred to a great number of Protestants and Orangemen who employed Roman Catholics. He felt he could speak freely on this subject as he had “not a Roman Catholic” about his own place. He continued by appealing to loyalists “wherever possible to employ good Protestant lads and lassies”.

On 9 April 1948, Member of Parliament EC Ferguson, speaking in Enniskillen the year before he resigned to become Crown Solicitor for County Fermanagh, said: “The nationalist majority in the county, notwithstanding a reduction of 336 in that year, stands at 3,684. We must ultimately reduce and liquidate that majority. This county, I think it can be safely said, is a unionist county. The atmosphere is unionist. The boards and properties are nearly all controlled by unionists. But there is still this millstone around our neck.”

This attitude was best summed up in the November 1949 issue of the official organ of the Ulster Unionist Council. Referring to local government votes, it stated:

“By the latter, the Ulster people put into office those who can wield for weal or woe, the power transmitted by our Stormont Government. Nor is this power negligible when one considers the making of appointments, the letting of houses, and the provision of health, medical, education and other services.”

The effect of this discrimination over decades left the Northern Catholic population with a sense of fear and isolation, and of being uprooted from their own space. For many, there was no way out other than to endure the humiliation of the unionist political regime. But that fatalism was not to last forever.