29 July 2012 Edition

Underlining partition

The Ulster Covenant

Northern unionists had consciously and deliberately created a defensive line across the map of Ireland based on their numerical, geographical and religious strength in the nine counties of Ulster. It is in these developments that we find the genesis of partition

FOLLOWING the review of unionist and Orange volunteers at Balmoral in Belfast on 9 April 1912 (Easter Tuesday) by Edward Carson and Bonar Law, leader of the Conservative Party, the unionist leadership began to think of an oath of loyalty to the unionist cause that would strengthen unionist opposition to home rule. In a conversation between James Craig MP (a senior member of the unionist leadership) and BWD Montgomery (Secretary of the Ulster Club in Belfast), Montgomery suggested using the Scottish 1643 Solemn League and Covenant as a model for their oath. Thomas Sinclair, a leading member of the Ulster Unionist Council, was then given the task of writing the first draft. Prior to its adoption by the Ulster Unionist Council, the final draft of the Covenant was submitted to the Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregational churches and the Church of Ireland for their consent and approval.

By using the concept of a Covenant, the unionist leadership were bringing the Protestant community back to that period of religious and political upheaval prior to the outbreak of the English Civil War. The clash of political and religious ideas between 1637 and 1660 brought in its wake a period of intense conflict across Ireland and Britain. At the very centre of these events were the Presbyterians of Scotland.

In 1637, the English King Charles I (1625-1649) sought to introduce in Scotland a Book of Canons to replace John Knox’s Book of Discipline and to impose a common English-style prayer book (Knox had been the leader of the Scottish Protestant Reformation). This action by King Charles caused outrage among Scottish Presbyterians; his use of his Scottish bishops to run Scotland added to this sense of outrage. All of this alienated two powerful elements of Scottish society: the Scottish nobility, gentry and clergy; and the Presbyterians. Scottish Presbyterians, referred to as the Church of Scotland, or the Kirk. The Presbyterians believed that Christ, not the king, was the head of their Kirk, and that power should flow upwards from the Kirk and not downwards from the king. This view ran contrary to Charles’s (of course), who saw himself as ‘The Godly King’, that as king he had a divine right to lead society and that power should flow from the king down into society.

A protest movement led by Presbyterian noblemen and radical clergymen gained momentum across Scotland. Eventually, the protesters sought to create a document that would unite and clarify the aims of their campaign. At a ceremony in Greyfriars, Edinburgh, in February 1638, large numbers of Scots had signed the Scottish National Covenant. In effect, the Covenant restricted the authority of the king and increased the power of the Kirk. The concept of the divine rights of kings ended with the Scottish National Covenant. The Covenant movement in Scotland became the dominant political and religious force in Scotland by the end of the 1630s. In 1643, the objectives of the 1638 National Covenant were later incorporated into the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant.

In 1643, royalist forces in England were in a dominant position to win the English Civil War waged between the royalists and parliamentarians. In an effort to undermine the strength of the royalists, the parliamentarians agreed on a Covenant with the Scottish Presbyterians. This was established on 25 September 1643. The Covenant provided the parliamentarians with military support from Scotland and the possibility of defeating the royalists; for the Scottish Presbyterians it provided a religious union between Scotland and England, with the potential to unite the churches of Scotland and England under a Presbyterian form of church government. In the spring of 1644, the Presbyterians sent four ministers to the North of Ireland to build support for the Covenant. They visited Carrickfergus, Belfast, Comber, Newtownards, Bangor, Ballymena, Coleraine, Derry, Letterkenny, Raphoe and Enniskillen. At Carrickfergus, 1,000 soldiers and civilians swore the Covenant. The Covenant had the characteristics and dynamics of a political and religious revival.

It was these characteristics that James Craig sought to replicate in 1912. The idea of the Covenant was a masterstroke by Craig. It tapped into the Protestant sense of their history, their independent thought, their commitment to their faith, and to the word of God. The use of the Covenant is deeply ingrained in the history of Presbyterianism. For Protestants the term ‘Covenant’ has a deep biblical resonance; it is considered to be a contract between God and his people.

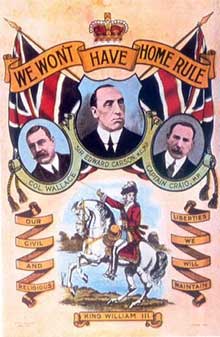

On 23 September 1912, the Ulster Unionist Council ratified the Covenant. On 28 September (Ulster Day), Edward Carson, after a religious Service in Ulster Hall, walked to the Belfast City Hall to sign the Covenant. In front of him was carried the Boyne Standard, which had been given to him the night before by Colonel RH Wallace, Belfast Grand Master of the Orange Order. On that day, the majority of the unionist population signed the Solemn League and Covenant.

To understand the events of 1912 there is a need to go back to the events of 1886 and the introduction of Gladstone’s first Irish Home Rule Bill. With the introduction of this Bill, the Northern unionist community were galvanised into action. Supported by the Conservative Party in Britain, four elements of Northern unionism were unified under the banner of the Orange Order: ‘Big House Unionists’, the new Protestant mercantile elite, Protestant political clerics, and the Protestant industrial working class and tenant farmers. Opposition to Home Rule in 1886, and again in 1893, provided Northern unionists with the ideological framework for growth. In fact, they developed to such an extent that, by March 1905, they were able to form a dominant and unified political organisation, the Ulster Unionist Council. What followed was the separation of Ulster unionism from unionists throughout the rest of Ireland. Northern unionists had consciously and deliberately created a defensive line across the map of Ireland based on their numerical, geographical and religious strength in the nine counties of Ulster. It is in these developments that we find the genesis of partition.

Northern unionists used their opposition to Home Rule as a means of consolidating the unionist political project in the North of Ireland. In each period of the three Home Rule Bills, unionist campaigns had the feel of a political and religious revival. Large events were skilfully used as a means of building the unionist political project: the Unionist Convention 1892, the Balmoral Review of 1912.

On 25 September 1911, the unionist path towards separation was strengthened. A resolution was passed at a meeting of the Ulster Unionist Council with the purpose of framing a constitution for a provisional government of Ulster in the event of home rule being imposed by the Westminster parliament.

1912 was a key year for unionists. On 5 January of that year, Colonel RH Wallace, Grand Master and Secretary of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ulster, applied to local magistrates in Belfast for permission to engage in basic military training. Orange volunteers and Unionist Clubs began to drill and train their membership in the use of arms. This drilling was a very early stage in the development of the Ulster Volunteer Force.

On 9 April 1912, Edward Carson and Bonar Law, leader of the British Conservative Party, reviewed Unionist and Orange Volunteers at the Balmoral showgrounds.

On 28 July 1912, Bishop John Tohill, Catholic Bishop of Down & Connor, called on the Catholics of Ireland to come to the aid of their “persecuted brethren” in Belfast. His appeal was made in the aftermath of the expulsion of almost 3,000 Catholic workers from the Belfast shipyards and other industrial sites across Belfast. These expulsions reflected a pattern of violence against Catholic workers that had emerged in 1886 when 300 Catholic labourers were expelled from the shipyard, and again in 1893 when 600 Catholic workers had been expelled.

1912 was also a defining year for unionists. Their defensive line was strengthened as they created the political and military capacity to mark out the physical boundaries of a future unionist state. With the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force in January 1913, three key institutions of unionism had consolidated their power base throughout the North of Ireland: the Ulster Unionist Council, the Orange Order and the UVF. These three institutions of unionism would later become the three foundation pillars of the Northern state as the Unionist Party, the Orange Order, and the RUC and B-Specials paramilitary police forces.

The Motorcycle Corps of the UVF in Belfast